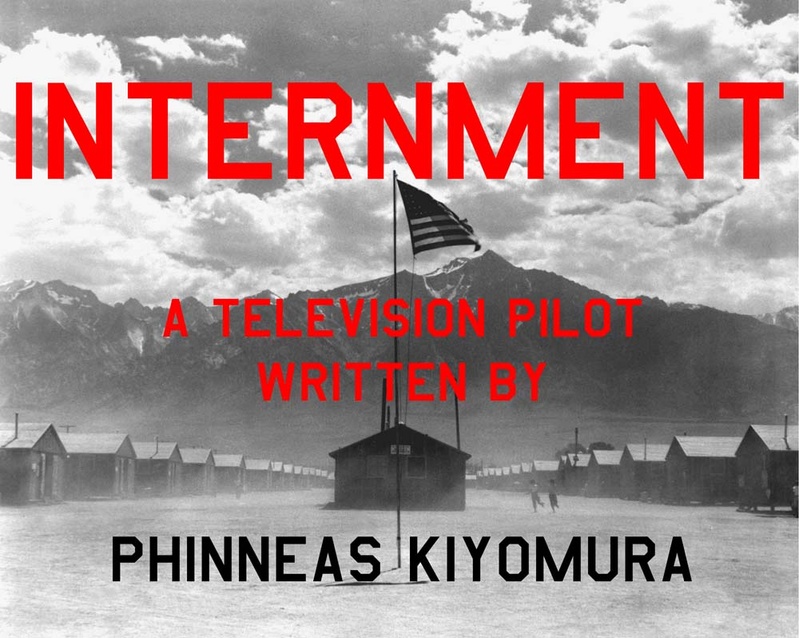

There is a script floating around Hollywood with Japanese Americans as central characters and the desolate landscape of an American concentration camp as the setting. Much has been documented about the wrongful incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II when President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 forcing all Japanese Americans to forcibly removed from their homes on the West Coast. Now, thanks to playwright, screenwriter, and actor Phinneas Kiyomura, a captivating look into the day-to-day challenges of camp life and family dynamics are dramatized in his TV pilot script, Internment—and hopefully coming to the small screen in the near future.

In Internment, the intricacies of family feuds, friendships, and romance are uncovered through the storylines of one particular Japanese American family. Through his fluid storytelling style and believable characters, albeit fictional, Kiyomura succeeds in portraying the harsh reality of life behind a barbed wire fence and guard towers. Who can resist a tantalizing drama that includes a colorful cast of characters and a touch of realism?

For Kiyomura, a Yonsei who is half Japanese and half Irish, acting and writing are nothing new. He wrote and acted in Lydia in Bed, a play lauded by critics and praised by Variety and LA Weekly. Roles on stage and in television abound as well as those behind-the-scenes as director and producer. His most recent play is Figure 8.

In this delightfully candid interview with Discover Nikkei, Kiyomura opens up about Internment, finding personal satisfaction and creative latitude in both writing and acting, and his cravings for Okinawa dango.

DN: What was the genesis of this project? How did the ideas for the script come together?

PK: Well, my father and my father’s family were interned, that strange word, during the war (they went to Rohwer) and it was a piece of history that we just grew up with. So, that was an inspiration, obviously. The camps weren’t a regular topic of discussion around the house, by any means, but as kids we were aware of the history. As a writer, I had meant for years to tackle the internment, but had never found a story that made sense for me to tell. And I was, and still am, scared of the topic, frankly. Scared that I’ll get the tone of things wrong, scared that I’ll offend or annoy the people who experienced the camps, scared that being a hapa makes me a less-than-legitimate person to tell this story and scared that these fears will weigh the material down with a lot of leaden studiousness.

But a television writer’s job is to come up with material, new material, every year, often multiple times a year, and I finally just realized that I needed to break that seal on my languishing ideas—and television pilots are very ephemeral objects, which gave me a feeling of liberation in tackling the topic. Then, of course, I had to come up with an actual angle into the world and the time.

Before getting into television and film, I was a playwright and actor, so my tastes tend to run in the direction of dirty little theatre pieces—i.e., complicated relationships between often dysfunctional people. That’s my bread and butter. So, the question was, how do I, doing what I do, meet this piece of history, this piece of America authentically? And I went with family. Struggle within family. Family drama with a bit of an early 1930’s/40’s American theatre flourish. And it just sort of popped out that the lead character was an unhappy son with a sort of brutish father, like in an O’Neill play or something, and that there would be all these fraught relationships coursing through the thing. I don’t remember exactly how Ken (one of the protagonists in Internment) became a doctor, but once he did become a doctor in my mind, I realized that this gave him a position of importance within the camp that could be explored and exploited. And suddenly his relationship with his sister and his mother popped in as well. And then all my real research began. And I read a bunch of things. No-No Boy was really important to me. I swiped a bit of the mother from John Okada. And his work made me feel at ease to be tough with the characters. And I went to Manzanar and walked around. And the place was so desolate, but also strangely beautiful, which I found confusing, but inspiring. And I found footage of a surgery being performed in Santa Anita, I think it was Santa Anita, and that made surgery seem like a reality I could explore, too, so Ken became a surgeon. And then I went to one of our family’s Christmas parties, and now that my relatives are getting older, they’re sort of letting loose with their histories. And my wife and I got a couple of my older relatives talking and they started telling stories and pretty much immediately disputing each others’ stories and all of that went into the blender and I just sort of jumped into the writing.

DN: Having read the script for the pilot episode of Internment, it is clear you are an exceptionally talented writer! The dialogue and witty exchanges between the characters are fantastic. How did you research the slang and idioms of that time period?

PK: That’s very nice of you to say. Can we be friends? As far as the slang, idioms, etcetera, again we can thank John Okada. The voice in No-No Boy is a very free feeling voice, a very intimate voice, and it has a kind of infectious feeling. I don’t mean that I intentionally imitated Okada, but I would peek at the book now and then. I’m also a great fan of those sort of early 20th century theatre titans: Tennessee Williams, O’Neill, Arthur Miller, and I love Hemingway, too. Kind of very obvious choices, but there you go. And all those writers infuse their own kind of poetry into their characters. I think, especially Miller uses this kind of blue-collar poetry in Death of a Salesman. And I just love charactery voices. I would watch and listen to interviews on Densho and just listen to those voices, and think about the voices of my older family members and just try to talk out loud to myself in their voices. And when I felt that I had them, I just let them talk. And later double check through Internet searches to see that what the characters say in the script could’ve been said at that time, or to find better versions. Dashiell Hammett and other hardboiled writers were also useful as reservoirs of slang and idiomatic expressions. And then a few I probably invented. I’m sure plenty of it is flat wrong, but can I perhaps claim poetic license? Is that allowed in a TV pilot? I’m not sure.

DN: Are any of the characters in Internment based on people you know? Perhaps anyone your father knew at Rohwer?

PK: My father was very young when he was in Rohwer, so there weren’t any specific people I drew from in that way. However, my great-grandparents did return to Japan before the war and adopted a young woman who eventually came to the states as a member of our family—she’s my aunt—and that story worked it’s way into the family story in a sort of twisted up way. Also, it turns out that my grandfather and grandmother eloped. My grandfather was a bit of a, uh, roughneck? That’s not the right word, exactly. But he wore a leather jacket, rode an Indian motorcycle, played ukulele in a band. And I love that image of him, and I wanted to have a few characters who kind of felt like that image.

DN: As a Yonsei Japanese American whose father was imprisoned at Rohwer, is it fair to say that Internment is a passion project?

PK: Yes. This is definitely a passion project. And one that I would like to see come to life. As in, get filmed, get put on TV, or the internet (hello, Netflix). If it never gets made in this form, I might rework it into a play or something else. Rock Opera? Probably not.

DN: When did you know you wanted to be a screenwriter?

PK: Well, I really, really fell in love with movies when I was a junior in high school. I mean, who doesn’t love movies, but, for some reason that year I had a lot of free time and I would walk around the block to the video store and rent a movie like every day or every other day and I watched everything. I was horrible to watch movies with because I’d seen everything. My friends would complain. And, when you watch everything you start with easy stuff, or popular stuff, but then you start looking at the weird and the hard stuff, and some of it is great and some of it is terrible but it’s all grist for the mill. And I started acting at just the same time, too, so acting and filmmaking came together in my mind. I started writing in college (I went to Cal State Fullerton) and we had a very small theatre library so I started writing my own scenes (which I never performed, but I wrote them anyway). And when I left college I acted and wrote in tandem for a number of years. I would substitute teach grade school in Bellflower during the day and then go do a dirty play in a dingy 99 seat theatre in Hollywood where everyone was naked and speaking in verse and then head back to teach third grade the next morning—but all that time I was writing, too. And in 2005 I had my first full length play produced at Theatre of NOTE in Hollywood. I thought it would be this little fun thing that no one would see. But the play, Lydia in Bed, got really nice reviews and we sold out our whole run. And I was like—OH, this is what I should be doing. Writing. But writing what exactly? And, almost immediately, I turned my play into a screenplay with a friend and we went through Film Independent’s Screenwriting Lab and I met a bunch of great TV people and I knew that film and TV was what I should be doing. And theatre, too. I’m somewhat agnostic on form.

DN: Between acting and writing, which is your preferred creative outlet? Both?

PK: Well, I don’t know. Yeah. Maybe both. Acting is literally more cathartic. I used to need to act in order to stay happy. Now, I guess I just don’t bother to be happy? Really, I love them both, but I do feel that I’m a little bit more writer than actor. Both are wonderful and horrible. Like everything else in life. Except hiking. Hiking is just horrible.

DN: What is your favorite Japanese dish?

PK: That’s the hardest question you’ve asked!!! Jeeze. I love onigiri. Gimme a warm rice ball any day. And is spicy salmon on crispy rice actually a Japanese dish? I could eat those all night long. What can I say? I’m a half Japanese kid from Long Beach. No, I know. Okinawa Dango. Mmm. Donuts.

* * * * *

Playwright, screenwriter, and actor Phinneas Kiyomura will oversee a reading of his TV pilot script, Internment at the Japanese American National Museum on February 8, 2015 at 2 p.m., with Chris Tashima directing. The reading is free with museum admission.

© 2015 Japanese American National Museum