Bunkado sits both physically and metaphorically at the crossroads of Little Tokyo.

Nestled in the shadow of the Miyako Hotel on one side and guarding the driveway that leads to the Koyasan Buddhist Temple on the other, Bunkado’s front door almost aligns with the crosswalk that splits First Street so a pedestrian could enter by walking a diagonal line from the Suehiro restaurant across the road in the Little Tokyo Historic District.

Officially, only the north side of First Street is designated as the historic district, but any amateur historian would have tabbed Bunkado as historically important as the business approaches its 70th anniversary in 2015. As with the other precious remaining Little Tokyo Japanese American family-run businesses such as Rafu Bussan, Fugetsu-Do, Mikawaya, S.K. Uyeda Department Store, and Anzen Hardware, Bunkado instantly evokes personal memories from generations of Southern California Japanese Americans.

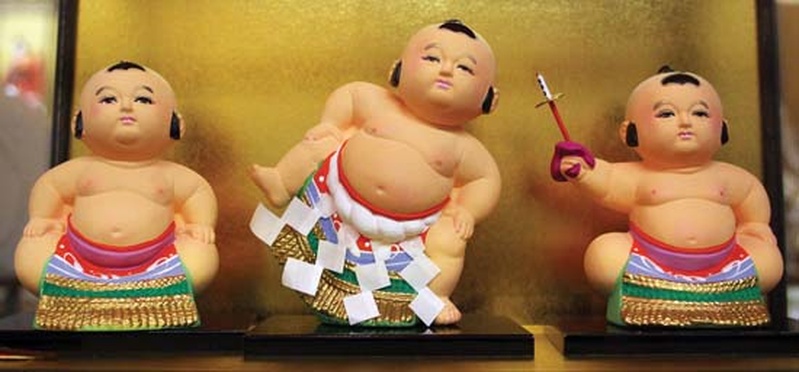

But, the gift store is unique, because its shelves are filled with cultural merchandise and quirky items that are difficult, if not impossible, to find elsewhere, but that most Nikkei recognize instantly.

On a typical weekday, two older Japanese American women approach the checkout counter and inquire about an order of Japanese calendars they had reserved. Irene Tsukada Simonian, the owner of Bunkado, pulls out a bag of five calendars and hands it to one of the women. Her friend immediately informs her companion that she found a whole section of these ornate, picturesque calendars from Japan and the two scurry away to inspect them.

“Who still uses paper calendars?” Irene asks, rhetorically. “But I have regular customers who come in every year for them. So I keep up the tradition.” Her one concession to contemporary tastes is to carry Kabamaru cat calendars, which have become a best-seller, thanks to a younger crowd.

A methodical trip up and down the aisles of the store reveals an assortment of specialized products: distinctive inks and brushes for calligraphy; specially designed scissors, vases, and kenzan (frogs) for ikebana; incense and ojuzu for Buddhism; origami paper and instruction booklets; hina, kokeshi, and kimono dolls; and, Japanese special occasion cards, including envelopes for koden money for funerals.

“Believe it or not, I have gotten orders from all over the world for koden cards,” Irene explains.

Do not assume that having so many unique items is making Bunkado an economic juggernaut. Business is not what it used to be in Little Tokyo’s heyday. Simonian notes that the majority of sales come from dishes and kitchenware. Once in a while, a production company calls, looking for hundreds of paper lanterns (which, because of the cost, come from Taiwan through a wholesaler) or other decorations for a movie or television set.

But, in truth, Bunkado continues to carry the cultural merchandise because Irene feels an obligation to do so. It is the connection she feels between the customers and the store that goes back to her parents and to her aunt and uncle, who founded the business.

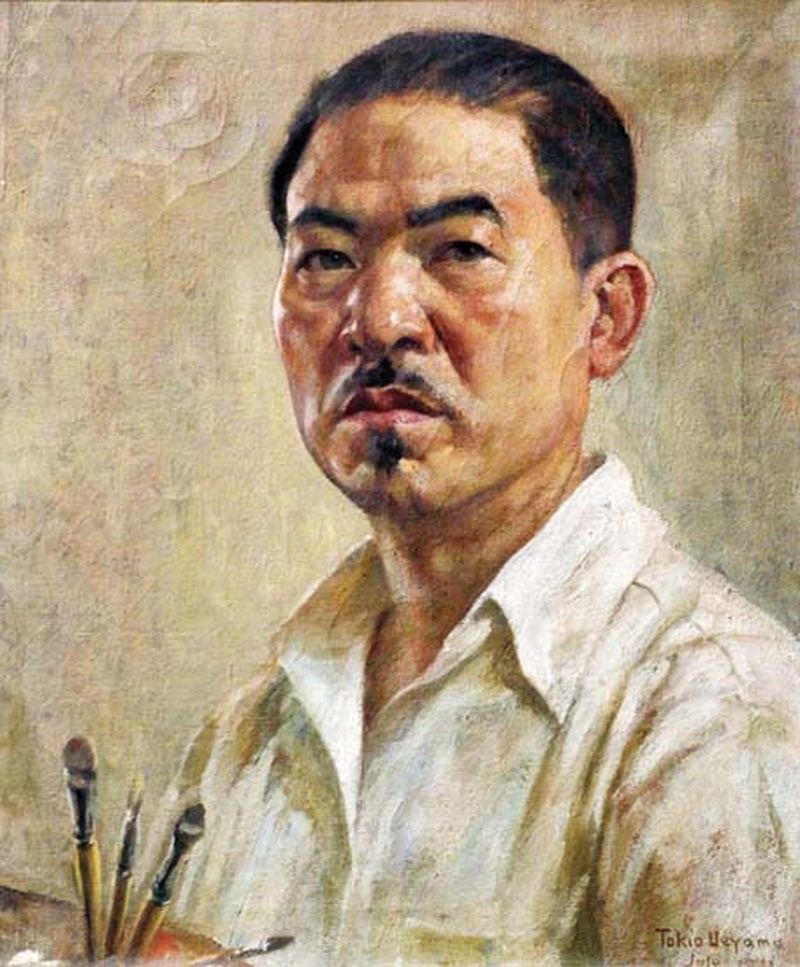

Irene’s uncle Tokio Ueyama was an artist who traveled and studied to be a painter before the war. He and his colleagues associated with famed photographer Edward Weston and Ueyama became friends with Mexican muralist Diego Rivera.

When he and his wife Suye were incarcerated by the government during the war in the Amache, Colorado camp, Tokio taught art and painted, including a portrait of his wife. That painting, simply titled Evacuee, was a featured work in the Japanese American National Museum’s exhibition The View From Within in 1994, almost 40 years after Ueyama passed.

Like so many artists, Tokio needed to do other work to make a living. So in 1945, after returning to Los Angeles, Tokio and Suye opened Bunkado in its current location. Bunkado means “house of culture” and according to Simonian, her uncle operated the business with that in mind.

Tokio displayed his own art in the store while selling art supplies. “Uncle had a vision that the store would be a venue for artists,” Simonian explained. However, Tokio passed away in 1955 and Suye was left to run the business by herself.

Irene’s father, Masao Tsukada, who was Suye’s youngest brother, and his wife Kayoko ran the Tsukada Gift Store on Moline Alley. When the store was forced to close to make way for the Japanese Village Plaza, Suye asked her brother to take over Bunkado. Irene has fond memories of her Aunt Suye (“she was like my ba-chan”), who lived with her family, and of the store, which she would visit after school at Maryknoll.

She remembers how everyone would patronize each other’s stores and Little Tokyo was a close-knit community. But, she had no intention of taking over the business.

Growing up, Irene studied ballet and even spent her summers at the Banff School of Fine Arts in Canada. She auditioned and was accepted to the Julliard School in New York City, leaving behind any dreams her parents had of her taking over Bunkado. Irene graduated from Julliard and stayed in New York, where she worked as a dancer. She eventually married and found employment at the Carnegie Corporations of New York.

But, after 17 years of living in New York City, Irene realized she was burnt out of big-city living and she missed the feeling of knowing everyone as she did in Little Tokyo when she was growing up.

After her father Masao passed away and Kayoko was running Bunkado by herself, Irene asked her mother if she wanted her daughter’s help. Although her mother spoke mostly Japanese, she told Irene in English, “I’m waiting.”

In 1992, Irene returned to begin the gradual process of learning how to run the store. Kayoko presided over the upstairs and left the downstairs to Irene.

Which brings up the biggest change to Bunkado from the old days: music. For many years, the upstairs was devoted largely to music from Japan. At one point, Bunkado sold more Japanese recordings than any other outlet outside of Japan. Famous singers such as Misora Hibari, Mori Shinichi, and Tendo Yoshimi made personal appearances at the store.

Today, upstairs is mostly closed to customers, but a walkthrough reveals the remnants of Bunkado’s remaining musical stock and how music changed over the years. The record album racks are empty, because vinyl was eased out by cassettes, CDs, and even laser discs. Irene is slowly selling off what’s left at a discount. She ponders what to do with the upstairs space in the future.

Her personal life has changed dramatically as well. In 2005, her first husband, Andrew Germain, passed away from lung cancer and her mother died a few months later. Left on her own, she forged on when she met Steve Simonian, who was also a widower. When they wed in 2009, Irene also became part of a family that included Steve’s mother, two children, and five grandchildren.

Once the Montebello police chief and chief of the L.A. County District Attorney’s Bureau of Investigation, Simonian is now retired, but occasionally comes to the store to act as an “overqualified security guard.”

Downstairs, an elderly man looks through a basket of key chains that have the different Japanese mon or family crests on them. Behind the checkout counter, dozens of the crests are displayed in a glass case. Many Japanese Americans come in, looking for their mon, but some are not certain which one belongs to their family. Some of these same customers remember Bunkado fondly from their childhoods.

“I like being behind the counter (near the front door), because I often hear people talking as they walk by,” Simonian explains. “They are happily surprised that the store is still here. It is amazing how attached people are to places like ours. And I have customers thanking me for continuing to be in business.”

Irene estimates that about half of her current customers are Asian. Since the Miyako Hotel is next door, visitors from Japan often pop in, discover Irene and the clerks can speak Japanese, and purchase omiyage to take home. Simonian maintains a website, but admits that online sales are small. But, the website is instrumental in making more people aware of Bunkado’s broad variety of merchandise thanks to Internet searches. Koinobori? Check. Noren? Check. Hanafuda cards? Check. Shogi and go boards? Check and check.

When the recent Hello Kitty convention was held in Little Tokyo and thousands of people flooded the area, Irene did not bring in new merchandise. She already had some Hello Kitty masks and she put them in the display window. But, she added, so many of the conventioneers were worn out by their activities that they mostly took a quick tour of the store and bought a few small items. But she was grateful for the new crowd that the convention and exhibition brought in.

As for the future, Simonian can’t say. She appreciates that her husband Steve “understands the significance of Bunkado.” Irene wants to repay her parents, her Aunt Suye, who she calls her guardian angel, and her Uncle Tokio, who in a way never left the store.

When you visit Bunkado, walk to the southeast corner of the store and look up on the wall. There is a framed painting of a man, serious and unsmiling. It is Tokio Ueyama’s self-portrait that he painted, Irene believes, near the end of his life. Lots of spirits are clearly watching over Bunkado.

“It’s more than a business,” Irene says, with a smile. Another customer has found what he sought, a large go board, and he marches to the front to pay. “It just feels right.”

* This story originally appeared in the holiday issue of The Rafu Shimpo on December 9, 2014. To purchase a copy of the issue, call the Rafu Shimpo at 213.629.2231.

© 2014 Chris Komai; The Rafu Shimpo