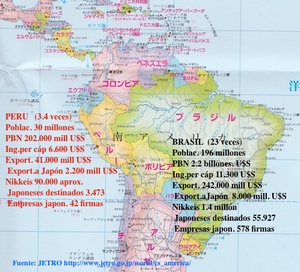

It has been a quarter century since Japanese migrant workers from South America arrived in Japan, but to Japan, the host country, these migrant workers are from "South America," and there has been little awareness of the differences in their countries of origin or their reactions to support measures. The largest Japanese community in South America is Portuguese-speaking Brazil (1.4 million people), and before the Lehman Shock in 2008, there were 310,000 Japanese Brazilians living in Japan. On the other hand, Peruvians, who represent the Spanish-speaking countries of South America, had about 60,000 people in Japan and 90,000 in their home country. As of the end of December 2013, there were 180,000 Brazilians and 48,000 Peruvians living in Japan. In the five years since 2009, the number of Brazilians living in Japan has decreased by 130,000 (just over 40%) and the number of Peruvians by 12,000 (just under 20%).

Immediately after the economic crisis, the Japanese government implemented employment support measures and a program to support repatriation (payment of travel expenses for repatriation), 1 but Peruvians and Brazilians in Japan responded differently. From the start, there was a high proportion of Peruvians participating in the employment preparation training, which was a Japanese language course lasting an average of 120 hours, and it was clear that they had a strong desire to continue living in Japan. In addition, 19,000 Brazilians participated in the travel expense subsidy program, and even if Peruvians and other nationalities were included, the number was around 1,000.

Professor Toshio Yanagida of Keio University has conducted a detailed analysis of the differences between the two, and I will refer you to his paper2 , but I have also explained the differences between the two to local government administrations, NPOs, and Japanese government authorities whenever I have had the opportunity. Although much of the support for Japanese workers is carried out with Brazilians as the front line, it is impossible to expect the same results from all policies, even for foreigners from South America. Furthermore, at the field level, a certain degree of balanced response is required, and it is necessary to take into account the national characteristics, ways of thinking, and perceptions of support measures of both parties.

In the first half of the 1990s, there was much talk about Peruvians being fake Japanese descendants and a relatively high crime rate (mainly theft), but over the past decade the number of crimes has decreased compared to Brazilians, and there has been a considerable improvement in the degree of social integration of Peruvians as local residents and in the rate at which children complete compulsory education. Conversely, the rate of non-attendance and juvenile delinquency among Brazilian children is higher than that of Peruvians, even in terms of population ratio.3 High school graduation rates for both are in the 50% range, but fortunately in recent years the number of children of both genders going on to university or vocational school has been gradually increasing.

As Yanagida points out, many Peruvians and Brazilians live in the Kanto and Tokai regions, but Peruvians do not seem to be concentrated in one housing complex or district. As a result, they do not have much friction or exclusive relationships with local residents. In Hiratsuka and Aikawa Town, Kanagawa Prefecture, a large number of Peruvians live in some housing complexes, but at first there was constant friction with neighbors over garbage disposal and delinquency issues, and in some areas there were repeated complaints from Japanese parents that the number of foreign children attending nursery schools or kindergartens was overwhelmingly higher than that of Japanese children, but these issues were all resolved through discussion. In the late 1990s, Aikawa Town experienced a problem with the sale and purchase of stolen goods by thieves, but the Peruvian community implemented a "Stolen Goods Stop Campaign" and, thanks to police crackdowns, the crime was prevented from spreading. Since then, there have been no major problems in these towns, coexistence with local residents has been relatively smooth, and for the past 10 years or so they have been actively participating in town festivals and events. The same is true in Gunma Prefecture, Tochigi Prefecture, and northern Saitama Prefecture, where Peruvians are dispersed and concentrated in multiple municipalities, and while there are ethnic goods stores and Peruvian restaurants in only a few areas, there is no phenomenon of a "Brazilian town" like Oizumi Town in Gunma Prefecture, which has a large Brazilian population. This may be impossible in terms of numbers.

When examining re-entry data on homecomings, it turns out that Peruvians are not returning to their home country as often as we might think. Under the direction of Associate Professor Ayumu Takenaka, who was seconded from an American university to Tohoku University at the time, interviews were conducted with 50 Peruvian households in Kanagawa and Tokyo. According to the results, half of the households with a solid life strategy and who were enthusiastic about their children's education and learning Japanese accounted for never or only once in the past 20 years (this is only the result of this sample, and the data is currently being analyzed). Although factors such as the purchase of a home, car loans, and children's education expenses are influential, they responded that they really wanted to return to Peru, where the economy is booming now, and show it to their children. The desire of Peruvians to settle down is also evident in the rate of permanent residence acquisition, with nearly half having such status in the late 1990s (less than 30% of Brazilians).

Even without a clear life strategy, Peruvians are aware that they will face a tough job and business situation when they return to their home country, and they seem to be taking a more realistic approach than Brazilians. There is also a difference in their attitude towards their home country. This may be evidence that they understand that no matter how economically developed Peru becomes, the disparities and social inequalities that have existed for a long time will not be easily corrected. Nevertheless, some Peruvians in Japan have effectively used their savings to purchase multiple properties in Lima4 , and there are many reports of small-scale business success among returnees5 . The Peruvian government, like other emigrant-sending countries, also expects their compatriots living abroad to contribute not only by sending money to their families abroad, but also by making concrete investments in their own society, providing technical and specialized know-how, and acting as a conduit for cultural and international exchange with the countries they are relocating to, and enacted the "Law to Support the Return of Overseas Compatriots" a few years ago6 . Peruvians in Japan are investing in real estate through organizations such as the Japanese Mutual Aid Association in Lima, but as more and more Peruvian children, who are second-generation immigrants, are beginning to receive higher education in Japan, the time has come to make more strategic use of this human resource.

This is a great opportunity for the children of Brazilians and people from other South American countries, and how to utilize their cultural diversity and language skills. This challenge is a common goal, and it will surely increase their recognition and appreciation in Japanese society. Both Brazil and Peru are important resource suppliers to Japan, and in the future they will also become markets and investment destinations.

Even if they are the same Nikkei, the history, culture, language, social structure, political situation, etc. of their country of origin naturally have a large influence on them, and these characteristics are expressed in some way in Japan. Even if the reason for their arrival in Japan was "dekasegi," in the case of Peruvians, they came to Japan in a desperate situation where economic factors were combined with terrorism and a worsening security situation. In addition, some Nikkei people still have political instability and fear deeply etched in their minds, and they still have the same old distrust that even if their home country's economy improves somewhat, the social structure and political system will not change so easily. There may have been circumstances that made them remain in Japan that were not optimistic, and it is also true that they were hesitant to start from scratch again when they returned to their home country and educate their children in a place with many flaws in the education system.

On the other hand, Brazil is a major Latin American country, and its size and expectations are very high, so Brazilians in Japan proudly promote their presence and may have the "illusion" that they can always return to its embrace. However, the reality is more complicated, and with economic growth comes the need to deal with rising prices and high competition, making it difficult for them to readjust to their home society even after returning.

In any case, it is natural that there are differences between the two groups, and what is more important is that if these characteristics of these people were to be utilized more as "cultural resources" in Japan, their sense of fulfillment and hope in society would increase, and Japan would surely become a more attractive place.

Notes:

1. "Considerations on the return of Japanese descendants through the repatriation support program," June 2010 , http://www.discovernikkei.org/ja/journal/2010/6/16/nikkei-latino/

http://sv2.jice.org/jigyou/tabunka_gaiyo.htm Overview of the job preparation training conducted by JICE

2. Toshio Yanagida, "Chapter 6: Lifestyle Strategies of Peruvians in Japan - Through a Comparison with Brazilians in Japan," pp. 233-263, in Chiyoko Mita (ed.), Living in a Globalized World: The Transnational Lives of Japanese Brazilians, Sophia University Press, 2011.

3. "Verifying crime data on foreign visitors to Japan"

http://www.discovernikkei.org/en/journal/2013/7/5/delitos-de-extranjeros/

The non-attendance rate for Brazilian children is improving, but in some areas it still seems to be as high as 30-40%. There are also cases of dropouts among Peruvians, and it seems that there are children and students who end up not attending school, but some estimates put the figure at around 10%. References: Ishikawa Eunise, "Chapter 4: How families are involved in their children's education - migrant lifestyles and parental worries," pp. 77-96, 2005; Yamawaki Chikako, "Chapter 5: Japanese schools and ethnic schools - children caught in the middle," pp. 97-115, same year; Miyajima Takashi/Ohta Haruo (eds.), "Foreign children and Japanese education - non-attendance issues and challenges of multicultural coexistence," University of Tokyo Press, 2005.

4. You can open a savings account for overseas residents at the local Japanese mutual aid association Cooperativa Pacífico ( http://www.cp.com.pe ) through a remittance company in Japan called Kyodai Remittance ( http://kyodairemittance.com/es/ ). You can then use the savings to take out a mortgage or arrange for the purchase of real estate in one lump sum. Information on savings products for members living in Japan:

http://cp.com.pe/fileadmin/img/japon/Link_Web_PaciFijo/Link_Web.jpg

5. The monthly community magazine "Mercado Latino" published in Japan introduces business cases of Peruvians who have returned to their home countries. Many of them are restaurants, and they are introducing the know-how and management methods they learned in Japan.

http://www.mercadolatino.jp

6. Yamawaki Chikako, "Chapter 4: Questions Asked by Peruvians Abroad: The Future of National Identity in the Age of Globalization," pp. 136-163, in Latin American Diaspora (ed. Komai Hiroshi), Akashi Shoten, 2010. Law to Support the Return of Overseas Compatriots (Tax Benefits): http://leydelretorno.rree.gob.pe

http://www2.produce.gob.pe/produce/migrante/index.php

© 2014 Alberto J. Matsumoto