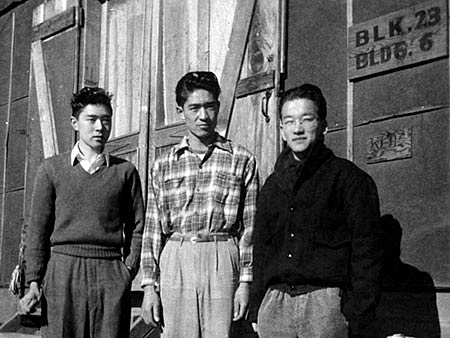

Like so many Nisei born in the United States during the early decades of the twentieth century, my father, Hiroshi Komai, left behind a large collection of personal artifacts after he passed away in 2004. Several years before his death, I did take the time to conduct an audio interview to learn about his pre-war years that I recorded and digitized for posterity. Since his passing, I have spent hours scanning and editing hundreds of photographs from his albums. Even so, there’s so much about his life that remains a mystery to me to this day.

Nisei are known for being relatively silent and discreet about their internment years, and my parents were no exception. I grew up in southern California during the 1950s and ’60s, and the few pieces of information that my father shared about that period of his life involved his camp employment as a baker and the fact that it took an inordinate amount to time for the administrators to provide coal and properly insulate the barracks.

I recall that when I was a young boy, my dad would occasionally pull out and play several Japanese pop songs of the pre-war era (Ryūkōka) from his collection of 78 rpm records. These were not commercially pressed recordings of high quality. Instead, they were duplicates (bootleg copies) produced on blank recording discs made of plastic or zinc-coated iron that he and several of his Nisei buddies made at their makeshift recording studio that they had set up at the Manzanar internment camp.

On a few record labels, my father had written the song titles (e.g., Niizuma Kagami) in either English or katakana, which I could read. In no cases, however, did he ever document the names of the recording artists. Up until his death, he regretted having lent his collection to a male acquaintance who proceeded to do irreparable damage to the record grooves by deploying a heavy phonograph needle and playing the tracks over and over. Only one of those records survived the war without incurring physical damage in this manner.

Despite their abysmal sound quality, these musical tracks have had a lasting impact on my personal psyche. Even though I could decipher and understand only a fraction of the lyrics, their catchy melodies have resonated with me over the years. One such musical number was the very popular and haunting ballad called Sendo Kawaiya. Another was Tsuma Koi Dochu. In the process of searching for a soundtrack to use in a family history documentary that I’m currently producing, I stumbled upon the names of the artists for both of these tracks, as well as several others in my dad’s record collection.

YouTube provided the initial breakthrough. Using my computer’s built-in software to enter text using Japanese characters, I found a YouTube video of one of my dad’s songs that contained an Internet link to the iTunes Store where I could preview and purchase dozens of tracks that had been digitized and compiled into five separate CDs (Japanese Retro Hits – The Pre War Years). One of the songs in the CD collection was none other than Tsuma Koi Dochu that I found out later was originally released on Polydor Records (No. 2428b). What caught my attention was that the recording artist’s name was given as Uehara Bin, which is what I distinctly remembered hearing my dad mention every now and then during our informal conversations. It never occurred to me back in my youth that Uehara Bin was the stage name or alias of the popular recording artist who had been born as Rikiji Matsumoto in 1908.

Researching further, I was able to determine the names of the artists for the following tracks that my dad had kept over the years: Sendo Kawaiya (Kikutaro Takahashi); Niizuma Kagami (Noboru Kirishima and Akiko Futaba); Chidori no Noodles (Noboru Kirishima and Misao Matsubara (aka Miss Columbia)); and Tabigasa Dochu (Shoji Taro).

There are still several songs in my dad’s collection where I haven’t been able to pinpoint the name of the recording artist or verify the song title. One such record contains my father’s working title of Wataridori (“Migratory Bird”). I found several listings on YouTube that contains the same title, but it’s not the same song. Another song that I am researching is a track that I’ve tentatively identified as Hatoba No Kataki.

As a side note, my father also kept a commercially pressed 78 rpm record manufactured by Victor Japan (No. 52351). Where and when he obtained this record is unknown. The song titles on this record were Koiwa Umibe De (Love at the Beach) by Mitsuko Watanabe, and Ano Onekoete (You Will Find Happiness Beyond the Mountainside) sung by Masao Fujiwara. Several years ago when I digitized both sides of the record, I noticed how clean the recordings were and immediately recognized that they had never been played on a phonograph system before.

I took the original disc to the Japan Center in San Francisco and asked one of the Japanese staff members to translate the record label and listen to the recordings that I had transferred to my iPod. The staff member told me that the text on the label contained several Japanese characters that are no longer in use today and that the recording was probably made during the late Taisho period (1926 or before). Needless to say, her revelation surprised me.

During the latter years of his life, my father suffered from a variety of debilitating illnesses that prevented him from learning the ins-and-outs of using a personal computer. I can only imagine what he would think and say today if he could listen to all these old songs with their original sound quality that they exhibited back in those bygone days.

© 2014 Dale Komai