In early May, a month before the 2014 World Cup, a judo film called A Grande Vitória (directed by Stefano Capuzzi) was released nationwide in Brazil. It’s a touching story of one juvenile, abandoned by his Italian immigrant father and raised in poverty, who finds a road to success in his encounter with judo. Max Trombini (age 45), the original writer, visited Nikkei Shimbun on May 9 and repeatedly emphasized that “life has its ups and downs.” The film is based on his Portuguese book Aprendiz de Samurai. (Apprenticeship of Samurai, published by Editora Evora in 2011).

When asked “What does judo mean to you?” he said it is his “principle of life.” We asked him a further question. “How is it different from other sports?” “Soccer, for example, is a means by which one can make money. We can say that it’s one of the very few choices for boys, born and raised in poverty, to make their way to the top of social hierarchy. But judo is not just about winning a game. There is this philosophy of bushido—the samurai spirit—and it’s a comprehensive sport philosophy that teaches people how to live and approach life. Judo has things that are lacking in Brazil. By spreading them, I want to follow the teachings of Master Umakakeba,” he said.

June 12 marks the opening of the 2014 World Cup in Brazil, attracting worldwide attention, but there are some Brazilians who feel the same way—which is the reason why a judo film, not a soccer movie, was released nationwide right before the World Cup.

In fact, Brazilian judo boasts 18 Olympic medals which account for almost 20% of a nationwide total of 102 medals won in the past. Without doubt, it is a sport that has won the most medals with an estimated number of more than 500,000 players. Given that Brazil has approximately 20,000 Japanese learners, the number is just incomparable. Surely people have the highest expectations for judo in the upcoming 2016 Rio Olympics.

A Scene from “A Grande Vitória” with leading actor Caio Castro and Nikkei model Sabrina Sato playing his lover

A Sport Exclusive to Nikkei Community in Prewar Times

Before World War II, judo was almost exclusive to the Nikkei community. The first and only exception was Mitsuyo Maeda (Conde Koma, 1880-1941, from Aomori). He opened a dojo—training hall—in North America (New York), won more than 1,000 matches across countries such as Mexico and Cuba, and is known as the true fighter of Kodokan (worldwide judo community), who gained high prestige in Europe, especially in Spain. While helping immigrants with their settlement in Belém, a city located at the mouth of the Amazon River, he taught jiu-jitsu to Gastão Gracie in his late years, from which the Brazilian jiu-jitsu originated.

Tatsuo Okouchi also taught judo first while studying pharmacy in the research institute of Doctor Jyokichi Takamine in New York in 1917 and re-immigrated to Brazil in 1924. Together with Seisetsu Fukaya, Soubei Tani, Futoshi Yoshima, Ryuuzo Akao, and Takeshi Kunii, he established the Brazilian Ju-kendo (judo and kendo) Federation (Federação brasileira de Judô e Kendo) and hosted many competitions until the outbreak of the war.

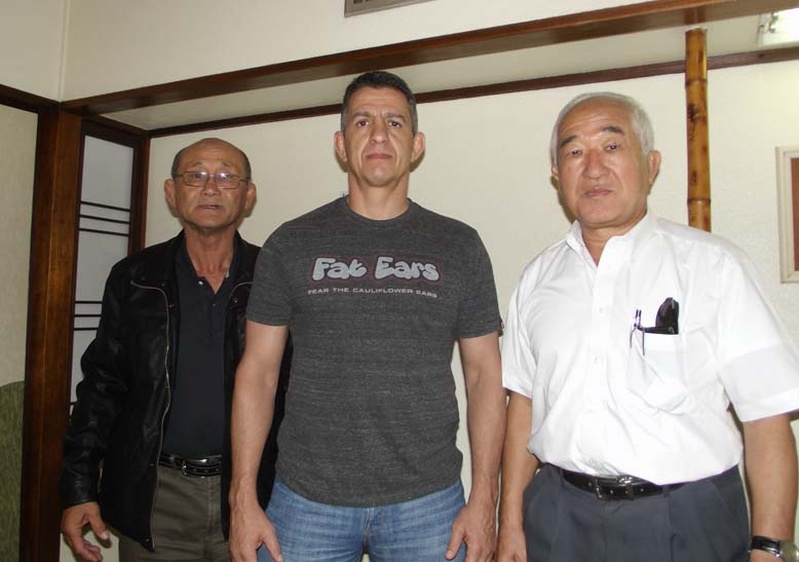

Max’s coach, Uichiro Umakakeba, (age 68, from Wakayama), settled in postwar Brazil, in 1956 at age 10 with his family. Like Umakakeba, those who were born in Japan but were raised in Brazil are called “Pre-nisei” (or Pre-second generation immigrants). What’s “pre-” about them is the fact that many are as fluent in Portuguese as Nisei with an understanding of Brazilian way of thinking. It’s a unique generation of “Japanese” people who have a high potential for becoming competent enough to run neck and neck with the elites of Brazilian society.

Umakakeba acquired his judo skills in Brazil, the skills that had been carried through the prewar time.

Knight Errantry in South America Brought Ishii an Olympic Medal

Judo in postwar Brazil owes much of its gain in popularity to Chiaki Ishii (age 72, from Tochigi, a naturalized citizen), a postwar immigrant who won a bronze medal at the 1972 Olympics in Munich. Ishii, not chosen as a designated candidate for the 1964 Tokyo Olympics, gave up on judo once and got on an immigrant ship the following day after his graduation from Waseda University with ambition to become a “big farm owner.” He was just 22 years old. As soon as he arrived in Brazil, however, he was encouraged to participate in a national judo competition and won first place.

Catching the momentum, Ishii decided to follow his dream again and wandered about South America for a year and a half. Beat me and I’ll give you 5,000 dollars—despite not knowing the language, this was his challenge to opponents, and he gained experience in a number of different combat sports such as boxing and professional wrestling.

Ishii met Umakakeba and taught him all of the techniques he had at the time. While seeing his pupils achieving solid results at competitions, he was frustrated at not being able to take part due to his non-Brazilian nationality. Then, Augusto Cordeiro the first president of Brazilian Judo Confederation (Confederação Brasileira de Judô), asked him if he wanted to become a naturalized citizen.

Most judo coaches in the Nikkei community at the time objected to the idea, insisting that he should not take part in competitions and instead teach the judo he learned in Japan to the Brazilian people. But Ishii did become naturalized and won a bronze medal. As a result, not only did the general public acknowledge him, but the Nikkei community also welcomed him as if they had wanted to do so from the beginning.

“People called me a traitor when I went to Japan afterwards. There were at least 20 to 30 players who were at the same level as me when I was in college. I never forgot how defeated I felt when I couldn’t make it to the Tokyo Olympic Games, and it kept me continuing on with my training for eight years in South America,” Ishii recalled. No other naturalized athlete has ever won an Olympic medal.

Umakakeba, Ishii’s No.1 pupil, currently runs a 700-mat giant dojo in the city of Bastos located in the rural area of Sao Paulo Province. He has brought up about four Olympic athletes there, including Tiago Camilo who won a silver medal at the Sydney 2000 Olympic Games. As a Pre-nisei, he was naturally well-skilled at teaching Brazilian people, which helped him further spread the sport in the country.

Max was born in Ubatuba, in the coastal area of Sao Paulo Province and was raised in poverty in a household that was abandoned by his father. At school, he got into fights and injured other students. Because of that, he almost got expelled. “Why don’t you do judo?” Encouraged, he started going to a local dojo which led him to mend his ways and stop fighting at school.

His mother, who was working as a housemaid, used up all her salary to pay the monthly fee for his dojo training. They didn’t even have money to buy a uniform, so Ishii’s mother made one herself, using a cloth of flour bags she got from a bakery. “She made one that looked exactly like a real uniform. But my neck grazed against the cloth and bled,” Max laughed, as he remembered the time.

He went to dojo three times a week and trained on his own everyday on the coast. “He must have gone crazy”—the neighbors talked about him. “I participated in kangeiko (training in the cold season) with Master Umakakeba, started training as a live-in, and learned the real judo,” Ishii recalled. From age 18, he went through rigorous training for four years as a live-in. He did strengthening exercises in the morning and had additional six hours of training in the afternoon every single day. “Desperately I trained myself to compete in the Olympic Games but I couldn’t make it. Since I had Italian citizenship, too, I thought about becoming a judo coach in either Italy or America. But then I got hired at a gym in Sao Paulo City.”

From Autobiography, Documentary to Film

When he published his autobiography, Aprendiz de Samurai, a youngster and recent film school graduate approached him. “I would like to make it a documentary film.” It turned out that the young director had connections with the Fernando Meirelles production.

It was Meirelles himself who liked the book and made an offer—“Brazil needs this film, especially the young generation. I will do everything I can.” Thus began the film production directed by the youngster. Meirelles, by the way, is the very person who was nominated for the Academy Award as the best director for his film, Cidade de Deus (City of God, 2002) set in a famous favela (slum) in Rio de Janeiro.

Coincidentally, last August at the World Judo Championships in Rio de Janeiro, Rafaela Silva (21 years old) won a gold medal as the first Brazilian female judoka. She was from the very Cidade de Deus. Just like Max, she got herself into constant fights at age five and was put into a NGO so she could take part in combat sports.

Having grown up in one of the most unfair cities in the world, she trained her mentality and body in judo and became a world champion. It’s a great example of Japanese sport philosophy complementing the weakest part of Brazilian society, turning it into something that now the country can boast to the world—a victory of judo “philosophy” that surpassed nationalities.

It took three years to complete the film, which is now in theaters, and leading actor Caio Castro lived in Max’s house for six months to learn everything he needed to learn about judo. “Uchikomi (repetition training) in the film is real,” said Takanori Sekine the chairperson of Brazilian Kodokan Black Belt Association (Associação Kobra de Cultura e Esporte–Akobrace) assuring the film’s authenticity. “I want the movie to be released in Japan, too. And if only someone could translate and publish my book there…” said Max. Umakakeba also has his own expectations. “Even in Japan, a judo-themed movie is rare. I want people to watch it in Japan as well.”

Umakakeba’s family business, a poultry farm, went bankrupt a few years ago. “I believed in the judo principle taught by Master Ishii that life has its ups and downs, so I paid back the debt and resumed both the farm and the dojo,” said Umakakeba proudly. Having watched his master’s way of life, Max repeats the teaching.

Ishii, who taught Max’s coach, published his own book in March this year—Pioneers of Brazilian Judo. It’s a rare chronicle of judoka who came before him, rather than his own life story. His three daughters all earned a black belt, and his granddaughter (a child of his eldest daughter) won the Pan-American Championships last year. “I want her to win a medal at the 2016 Rio Olympics,” he said, hoping that his granddaughter will make her mother’s “lost” dream come true.

After Rio comes Ishii’s fated “Tokyo Summer Olympics.” If any of his grandchildren or pupils wins a gold medal in 2020, it will surely be the homecoming of gold he has so long wanted.

© 2014 Masayuki Fukasawa