If you’ve ever visited San Jose’s Japantown, odds are you’ve stepped in a building constructed by the Nishiura brothers. Born in Nara prefecture and raised in the shadow of ancient temples, the two brothers, Shinzaburo and Gentaro, learned their carpentry skills from their father Tsurukichi, himself a skilled craftsman. The story of the Nishiura brothers and their superb aesthetic reflects how art is often integrated into our everyday lives, for example, within the buildings where we live, worship, play, and work.

Gentaro, the younger brother, came to the United States from Mie prefecture, arriving in Hawai‘i in 1905. A year later Shinzaburo joined his brother, and together they briefly worked in the shipbuilding industry before moving to Northern California. As time went on, other family members joined them there.

Utilizing their extensive carpentry skills and aesthetic sensibilities, the Nishiuras devoted their lives to constructing landmark buildings for the Japanese American community in Santa Clara County, such as the wood-framed San Jose Buddhist Church Betsuin, heralded as a prime example of traditional Buddhist architecture in the United States.

From the very beginning, the two brothers proved to make a good team: While Shinzaburo was a sharp mathematics whiz, Gentaro was more “sublime,” according to his son Kiyoshi, in an interview with the Japanese American National Museum conducted in December 1998.

The two brothers shared residences in both Mountain View and San Jose, and they worked to build countless homes in neighboring communities. In addition, their business increased as flower growers in Mountain View ordered glass greenhouses that required at least a month to assemble.

The Nishiura brothers soon were recruited to work on a variety of projects in San Jose’s Japantown, or Nihonmachi, beginning in 1910.

One of the Nishiura brothers’ first structures was the 1910 Kuwabara Hospital, now known as the Issei Memorial Building. At approximately the same time, they also constructed the Honganji Mission; five years later they built Okita Hall, now called Aikido Hall, a Japanese theatre. The Nishiuras were also hired to help constructed the Japanese Pavilion at the Panama Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco in 1915.

The Nishiura brothers, who were devout Buddhists, also continued to build temples: on June 13, 1913, they and architect K. Taketa signed a contract to build the first Independent Buddhist mission at 630 North Fifth Street. According to temple records, the cost of construction—including materials—was less than $4,000.

Without a doubt their defining project was the building of the San Jose Buddist Church Betsuin in the mid-1930s. “This was the one that put them over the top,” stated Gentaro’s son Kiyoshi. “They put their heart and soul into it.”

Working with architect George Gentoku Shimamoto, the college-educated Issei designer of the Oakland Buddhist Church, the Nishiura brothers traveled to Oregon in order to secure “clear” top-quality lumber, which was then dried in a kiln. After the framing was set on the foundation, large pieces of lumber were hoisted to the roof without the aid of modern-day forklifts and cranes.

The temple was completed in 1937 at a cost of $30,000. A formal dedication ceremony was held three years later, upon the arrival of Buddhist articles and shrines from Japan donated by Santa Clara Valley residents.

The Nishiura brothers continued their work on projects that ranged from the ornate to the more practical. When entrepreneur H. K. Sakata purchased the Gilroy Hot Springs in 1935, Shinzaburo and Gentaro helped to constructed cottages within the mountain retreat. In 1939 they were reunited with architect George Shimamoto to construct the Japanese Pavilion for the Golden Gate International Exposition on Treasure Island; after the World’s Fair ended, they reassembled the structure on the Gilroy ranch owned by garlic farmer Kiyoshi Hirasaki.

Carpentry was a calling and a passion for the two brothers, not simply their occupation. For example, when the San Jose Buddhist Church Betsuin was reported to be on fire at the beginning of World War II, Shinzaburo defied the government curfew that restricted Japanese activity after six in the evening. “I don’t care if they catch me—let them catch me,” he said, according to son Harry. “I’ve got to fight the fire!” A homeless man had apparently built a small fire to warm himself, and the blaze left a thirty-inch-diameter hole in the church’s floor.

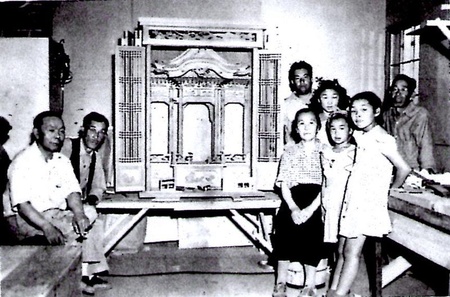

Due to the evacuation, the brothers were forced to give away their priceless Japanese tools or sell them at cut-rate prices, and they had no choice but to temporarily discontinue their business. Even after being incarcerated in Heart Mountain concentration camp in Wyoming, however, their hands could not stay idle: the internees were prevented from bringing certain religious items into camp, so the brothers remedied the situation by carving beautiful Butsudan (Buddhist altars) so that services could continue.

Collection of Chiyoko Nishiura.

Immediately after the war the Nishiura brothers resumed their construction operation in San Jose, and they welcomed the addition of the next generation: Kiyoshi, the son of Gentaro, and Harry Shinichi, the son of Shinzaburo.

The business eventually closed its doors in the mid-1950s, and all the principals have since passed away (with Kiyoshi most recently on January 1, 1999). However, the Nishiuras’ legacy indeed remains to this day, to be experienced by any passerby visiting the heart of San Jose’s Japantown.

“I remember so very clearly,” recollected Diana H. Nishiura, daughter of the late Harry Nishiura, “that my grandparents lived under conditions that we would describe today as at the poverty line, and yet they worked hard, with an almost religious dedication to their work. They lived without most of the comforts of life. I marvel today at their achievements and how such a unique and lasting contribution to the community was humanly possible.”

* This article originally appeared in the Winter 2000 issue of the Japanese American National Museum Member Magazine.

© 2000 Naomi Hirahara / Japanese American National Museum