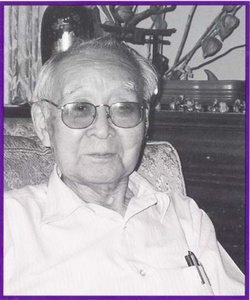

The story of Chicagoan Art Morimitsu’s life is the story of a community—the story of Japanese American immigrants whose sons and daughters triumphed over hardships and discrimination to make their way as exemplary Americans. At age 86, Morimitsu knew that his life’s story was the stuff of legend. In a June, 1998 interview his mischievous grin and twinkling eyes indicate the pleasure that it gives him to recall the events of his long life of hard work and service.

Morimitsu’s father was a laborer on a sugar plantation in Hawai‘i, his mother was a picture bride, his uncles farmers in California’s Central Valley. After the San Francisco earthquake in 1906, the family settled near Sacramento. Morimitsu worked his way through the University of California at Berkeley during the Depression as a “schoolboy” or house servant. He graduated from college in 1936. Jobs were hard to find, especially for people with Asian faces. College-educated Nisei (second generation Japanese American) were forced to work in community restaurants and fruit stands, and Morimitsu first worked in a Japanese gift shop in San Francisco’s Chinatown, then as a truck driver for a laundry.

The State Civil Service offered just about the only opportunity for a Japanese American to get “a half-way decent job,” and young Morimitsu passed the exam. He worked for the 1939 World’s Fair in San Francisco, and when the Fair closed, transferred to the Civil Service agency in his home town of Sacramento. He was living in Sacramento with his family when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor and the United States entered World War II.

Morimitsu reflects on the events immediately after Pearl Harbor, and how the sentiment in Sacramento swung from what he experienced as fair and friendly to blatant discrimination. “I suppose you know,” he says, “that this anti-Japanese thing had been going on for a long, long time in California, way before the war. The owner of the Sacramento Union had a lot of Nisei friends, and he tried to tell the subscribers to be fair and to calm down the people, but he lost a lot of subscribers. It got to the point where there was too much propaganda and it was too strong. The Italians and the Germans they had people in Congress and prominent people, but we didn’t have anybody like that.

“We started hearing the rumors that Nisei in the State Civil Service were going to be losing our jobs, and four of us went to San Francisco to meet with Mike Masaoka. Mike was a young fellow from Salt Lake City and he representing the JACL (Japanese American Citizen’s League). We tried to find out what we could do, but we didn’t have any power, of course. All of us just lost our jobs.

“I was older than most of the Nisei, I was already thirty. Most of the Nisei were in their early twenties or younger. And of course after the war broke out they picked up all our leaders; ministers, priests, school teachers, business people. Only ones who were left in Sacramento were the young people. And the anti-Japanese saw a chance to get rid of all the Japanese farmers.

That’s basically what happened.

”My uncle was a truck farmer and my future brother-in-law had an orchard and I remembered that the crop was almost ready and they didn’t know what to do, invest in seed or what, and all of a sudden they had to leave and lost everything. They got a real raw deal.” His voice fades, as he recalls the painful past. Then he remembers his visitors and continues the story.

Morimitsu and his family were sent to an assembly center outside of Sacramento (“terrible, just outdoor toilet facilities, terrible”) then taken by train to the Tule Lake concentration camp. “I was a bachelor, and it was kind of an adventure,” he remembers “but the people who had the really hard time were the families with small kids. I know the mothers used to complain to me, ‘You know we can’t control the kids any more. They’re running wild. There’s no family now.’”

“We were having this ‘no no’ problem. The Army sent recruiters to Tule Lake. I had no formal Japanese language training, but they gave me some simple tests and they were so desperate that they accepted me. Only about four of us went from Tule Lake. Eventually, when I went to the L.A. museum, I found out that Tule Lake had the lowest number of volunteers because they had so much rumpus going on there. Anyway, for me that was the best move I ever made, because I saw three-quarters of Asia at government expense after I got in.”

After intensive language training at Camp Savage, Morimitsu’s Nisei language team was assigned to the famed Mars Task Force in the Pacific. He remembers the long journey by ship to Australia and India as “the worst two months of my life.” He transforms his experiences behind enemy lines along the Burma Road into funny stories about taking care of a Texas Cavalry pack mule, sleeping in the open, getting supplies by parachute. He is grateful, he says, for his boy scout training, and learning to cook outdoors.

There were few Japanese prisoners to be interrogated. “They had been taught, ‘if you’re captured, don’t come home’,” he says quietly. Toward the end of the war. Rather than surrender, they knew the war was over…

After the Burma campaign ended, Morimitsu was sent back to India, then ordered to North China, where he served as an interrogator/interpreter during the surrender of 60,000 Japanese soldiers. Time slips by as he tells stories about the war—a raid on a Japanese headquarters, interviewing a Chinese warlord, a Japanese general. There are stories about buddies whom he will never forget, friends whose bravery went unrecognized.

When Morimitsu left the service, he married his wife Virginia, whom he met on furlough in Chicago where his family had relocated during the war. His wife-to-be had left camp at Manzanar to work in a relocation hostel in Chicago. “We were engaged for two years while I was overseas,” he says. She wrote to me every day. Sometimes letter number seven came before letter number four.” There was a pause. “You know, even though lots of people complain about internment, I don’t complain,” he says. “Because she was formerly from Southern California and I would have never met her except for the war.”

The Morimitsus joined the vigorous post-war Japanese American community in Chicago. He took a mail-order course for G.I.s, then built a successful carpet service business. They raised three children, twin daughters Cathy and Carol, and son Philip. “She was the one who raised them,” he says. “I was too busy running the business.”

In his later years Morimitsu became a well known community leader and activist in the Midwest. He remembers with pride the ten years he spent fighting the Japanese American redress. His assignment, he says, was to get veteran’s support for the redress movement. Working with the JACL’s Legislative Education Committee (LEC), Morimitsu lobbied members of Congress, the Veterans of Foreign Wars, and the American Legion, reminding them of the heroic wartime service of the Nisei in Europe and in the MIS. “They weren’t too concerned about loss of property and so forth,” he chuckles, “but taking away constitutional rights, that’s a no-no for the American Legion.” In 1990, Morimitsu received the JACLer of the Biennium Award for his work on the redress campaign.

Morimitsu was President of Chicago’s Japanese American Service Committee for twelve years, headed a successful fund-raising campaign to build the first Japanese American nursing home in the Midwest (where his 111 year old father lived), and in recent years was also an active member of the Museum’s Board of Governors. Told that Nisei veterans’ reunion is being planned in Los Angeles for the year 2000, Morimitsu flashes a grin. “I’ll be there!” he promises.

Sadly, Art Morimitsu died on September 1, 1998. He’ll miss the reunion, but his legacy lives on, in the memories of all those whose lives he touched and in the institutions he helped to establish. From house servant to Museum Governor, his life is an integral part of the Japanese American community story.

*This article was originally published in the Japanese American National Museum Quarterly, Winter 1998-99.

© 1998 Japanese American National Museum