Read Part 1 >>

It heals the turbulent world caused by the fight to win or lose, and spreads to the masses.

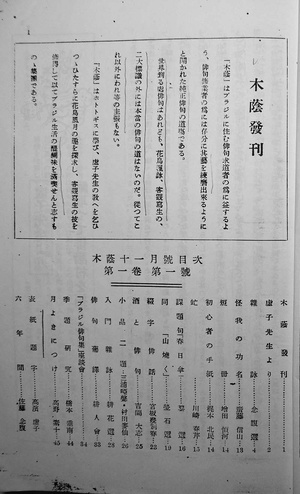

In November 1948, after the end of the war, in the midst of the Japanese community being divided by the struggle for victory and defeat, the monthly haiku magazine "Kage" (Shade of Trees), published by the Hototogisu school and presided over by Nenpuku, was launched in the city of São Paulo.

The opening page of the first issue contained a letter of encouragement from Takahama Kyoshi. The editor's note reads, "It has been about twenty years since the seeds of haiku were planted in Brazil, and more than seven years since the publication of the haiku magazine "Kage" was planned. During this time, 40 local haiku groups have been nurtured, and the number of haiku friends that they support has exceeded 500. A Portuguese column was established, and the authority on botany, Goro Hashimoto, used his knowledge to present research on seasonal themes unique to the area.

The haiku magazine "Kokage" celebrated the publication of its 300th issue in September 1973. In 1979, it published "Kokage Zassai Senshu" (1979, Nagata Shoten, Tokyo), a collection of over 2,500 carefully selected haiku from among the 57,000 or so works. Nenpuku passed away on October 22, 1979, and "Kokage" ceased publication with the October issue of the same year (volume 372).

So his younger brother Ushi Doji (real name Sato Atsui) launched the magazine "Asahi" in November of the same year and took over as editor. After 40 years of work, he completed the haiku dictionary "Brazil Saijiki" (Nichimae Sosho) in 2006. The dictionary contains seasonal themes such as weather, astronomy, geography, plants, animals, and human affairs, categorized in the order of the four seasons, and contains approximately 2,500 entries. After his death in 2011, his wife Toshikazu continued to publish "Asahi," with the August 2014 issue being the 418th edition.

Hisakazu explained, "Nenpaku Sensei popularized haiku while traveling around the colonies. It was a time when there wasn't entertainment like there is today, and before the war everyone would think, 'I'll make some money and then go back to Japan,' but after their homeland lost the war, they no longer had the time for that. Many people cried for their longing for Japan, and haiku was the only way to heal that nostalgia. That's why haiku are filled with strong feelings of patience and resignation."

At the time, writing haiku was the very act of "living as a Japanese person," and was a "medicine" to heal the mental illness caused by intense nostalgia. A part of that feeling is captured in the opening verse, "One meter of sadness."

Masayuki Mizuno, who worked as a reporter for the Japanese language newspaper Paulista Shimbun and the Nippaku Mainichi Shimbun immediately after the end of the war, believes that "the integration of the colony after the war began with literary activities such as haiku." The Japanese community, which had been divided by the struggle for victory and defeat, was gradually healed by literary activities that dealt with the commonalities between the two sides, such as "Japanese culture" and "nostalgia for the homeland." It seems that such a gentle integration activity was also the hidden mission imposed on haiku.

Nenpuku published his first full-fledged collection of haiku, Nenpuku Kushu (Kurashi no Techosha, Tokyo), in 1953. At that time, helpers from Japan came one after another. In April 1953, the editor-in-chief of Omo, Hoshino Tatsuko (daughter of Takahama Kyoshi), and the female haiku poet Nakamura Nanako came to Brazil on a haiku pilgrimage, followed by the great poet Takano Soju, and the world of sketch haiku based on flower and bird poems was filled with an extraordinary enthusiasm, ushering in the golden age of the lesser cuckoo.

During the postwar heyday of haiku, Nenpuku had over 1,000 disciples and spent half the month traveling around the country teaching haiku to immigrants, making a living from that, a rare figure overseas.

In the afterword to the aforementioned "Nenpuku Kushu," Nenpuku heartily writes, "My haiku are merely a record of the life of an uneducated immigrant with a modest income, and there is probably not a single poem that would be appreciated by the general public. However, haiku are like my life."

"Playing guitar, resting on the road with flower coffee" (Nenbaku)

"Is happiness something unknown to the world?" (Nenbara)

Appreciated in his home country, Haikai

In 2013, Hattori Tane (92, Kumamoto), a resident of Manaus, the capital of Amazonas, won the grand prize in the "General Category B" (over 40 years old) at the 24th "Oi Ocha New Haiku Awards" with his haiku "The first mirror of a 92-year-old in the Amazon," becoming the first Brazilian to win the award. Over the past 20 years, it has become common for many people to submit haiku to Japanese haiku competitions and win prizes. This work was selected from 1,652,11 haiku submitted mainly from within Japan. Tane is taught by Hoshino Hitomi, a senior disciple of Nenpaku, making him a disciple of Nenpaku.

"Hatsukagami" is a seasonal word for New Year's, and he explained, "It represents the feeling you get when you change into a kimono to celebrate New Year's and look into the mirror with renewed spirit before going to a family gathering. I have lived in the Amazon for 60 years, and whether I cried or laughed, it always healed me in the end. This poem suddenly came to me when I felt truly grateful to the Amazon."

In 1954, Tane and his family of eight settled in the colony of Treze de Setembro (formerly Guaporé) in Rondônia state. Of the many postwar settlements, it was one of the most difficult. The painful experiences unique to immigrants are sublimated into his works, which are highly regarded in his home country.

* * * * *

On the day of the memorial service, Hisakazu (second generation, Bastos) sat in the center. In his opening remarks, Genichi Sugimoto, the chairman of the convention, reminisced about the modest haiku gathering 70 years ago, huddled together under the dim lamp of a farmhouse, and said, "My direct and disciples from back then have grown old and somewhat less energetic, but I intend to continue to follow the teachings of Nenpaku Sensei and work with everyone to compose poems about the scenery and scenery of this vast country as long as I live."

When asked about his thoughts on this year, moderator Hamada Kazuana nodded and said, "The majority of the people who gathered are from the generation of Nenpaku Sensei's disciples who didn't know him personally. But it's wonderful that it's still going on."

Even now, 106 years after the first immigrants, the Nikkei Shimbun newspaper has a weekly literary page on haiku and tanka. The fact that this competition is being held 36 years after Nen's death suggests that his wish to "create a kingdom of sketch haiku in Brazil" is being passed down.

The first leader was Masuda Tsunehisa (deceased), one of Nenpuku's most senior disciples, and the Portuguese word "Haikai" is gradually spreading throughout Brazilian society.

© 2014 Masayuki Fukasawa