Read Part 1 >>

Were you ever drawn to any other traditional Japanese instruments like the taiko?

Well, it looks to me that today’s taiko players take a totally different approach to training themselves. Mr. Daihachi Oguchi, a jazz percussionist, considered to be responsible for transforming O-suwa style ceremonial taiko into a stage performing art form had yet to organize his group when I was in Japan.

The first taiko performance in Vancouver was by “Ryujin Daiko” from Fukui-ken at the first annual Powell Street Festival in 1977, which I was the project sponsor under a federally funded program “B.C. Centennial Arts Workshop.” The Arts Workshop became instrumental to coordinate and implement the major centennial celebration programs and events. About two years later, the original “Ondeko-za” (later became “Kodo”) appeared in Vancouver and played two benefit concerts for Tonari-Gumi. Therefore, I still have some contact with the original members today.

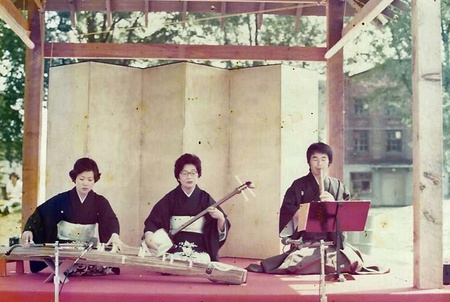

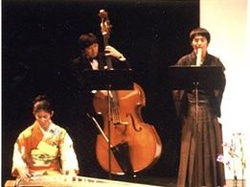

Anyhow, the shakuhachi discipline must be a personal pursuit from the outset and one has to have some preparedness by studying classical shamisen music (jiuta), koto music, and shakuhachi traditions for many years before experiencing a public performance. Taiko music in that sense, is more oriented to be used as a tool to develop team/group/community based participatory program. But in a positive sense, it’s a wonderful example of visually theatrical and physical performance. In the past, I played with many taiko groups or soloists, African drummers, and other percussionists, but, honestly, as I get older, I just enjoy playing alone at home everyday.

Do you still perform today?

I don’t enjoy the performance any longer. However, I still respond to surviving families and community requests and play on some ceremonial occasions and events if requested. They are to me very special way of parting with the passing friends or community members. My last performance was in New Denver in summer on their Internment Heritage Centre’s 20th anniversary event. I feel like I have some of my own roots deep into the community there, starting from Mrs. Chie Kamegaya.

Mrs. Kamegaya was a good friend of mine too. I visited her and many other people in New Denver like Pauli Inose, “Sockeye” Hashimoto, “Nobby” Hayashi, and many others when I lived in the Kootenays. Did you know the artist Koko and her husband Paul who live there?

Koko is one of my longest time friends whom I met just about a week after I came to Vancouver in 1972. Today, she is like my big sister who has helped me tremendously throughout my life in Canada. I was invited to participate in their performances many times, while Koko and Paul were running “The Snake in the Grass Moving Theatre” based in Vancouver. They always host and put me up at their residence there in New Denver.

What was your connection to Mrs. Kamegaya (1909-1994)?

My participation in the inauguration ceremony of the NIHC happened by the request of Mrs. Chie Kamegaya. She wrote a heartfelt letter to me disclosing the fact that she had brought a shamisen to Canada and kept it almost secretly for her own enjoyment. She said she wanted to play with me a nagauta (shamisen) piece called “Matsuno Midori.” The shakuhachi traditionally is not played in nagauta, however, thanks to my last master, Kikusui kofu, I played some of such pieces with nagauta musicians.

Unfortunately, her health deteriorated and could not realize her dream of playing the piece with me. but she came out to my concert in the following night in Silverton. Someone by the name of Ruby Truly brought her out in the wheelchair. It was the last opportunity for me to bid farewell in tears to her.

By the way, my master’s name is Kikusui Kofu and used to own and run the Shakado Shakuhachi Dojo (Shakado-temple Buddhist Shakuhachi Institute) in Seiryoji-temple (a.k.a. Shakado) in Saga district of Kyoto. That means I lived in the Seiryoji-temple for two years with my master—still a fond memory!

What is it like to be a shakuhachi player in Japan these days?

As you probably know how popular or unpopular the shakuhachi is in Japan, although I am not necessarily in touch with the today’s situation on a regular basis. One thing I really appreciate today, though, contrary to the environment of my time, is that shakuhachi music is commonly used in the production of radio, TV, film, and other media. This means a lot more jobs for the pros, in particular, for young emerging musicians.

The other side of the coin is the fact that they are in much harder competition due to a lot more music schools/universities and the graduates there of. For comparison, 90 percent of the pros survived then were based in Tokyo—the centre of the modern Japanese culture.

In fact, the reason why I chose and studied with Kikusui sensei was that he was the only pro player in Kyoto back then. The professional opportunities are mostly in Tokyo. Kyoto is the place where the koto and Jiuta music originated some 400 years ago. But there are far fewer opportunities to play professionally in the Kyoto-Osaka area.

My dojo was well known as the place in Kyoto to accept foreigners to study shakuhachi music. During my time in dojo, I was responsible for teaching the foreign students. We had about 10 of them then. Thus, I ended up living in the freedom and liberty of Canada today.

What do you think about the state of traditional Japanese music in Japan these days?

The Yoshida Brothers of the Tsugaru-jamisen (shamisen) are the most well-known, recognized, and of course, most commercialized performers in this genre, northern traditional folkloric music from Aomori. They are by far one of the best example of Japanese performers/musicians; Kodo is another group.

When it comes to my playing in Canada, It’s been a long and trying experience, starting from playing in the Gastown area streets, coffee houses, art galleries, and museums to my own recitals and recordings. And to concert tours, educational workshops, lecture, and demonstrations, etc. For some reason, my music and I did not have to struggle much.

My best friends were all those local musicians—jazz, folk, bluegrass, or else. Vancouver Folk Music Festival Society and the Coastal Jazz and Blues Society and the likes. They helped me a lot in referencing and marketing myself in my early career. So, my music found the way almost immediately. I was lucky in a sense that there was a professor and shakuhachi master at the University of British Columbia who talked about how difficult it is to play the instruments because they are primitive and handcrafted products. He used to lecture the audience right at the opening of his concert. He surely had a very difficult time to produce a sound.

I personally thought my music was well received in a concert format. I even thought the audience here had no knowledge about the shakuhachi music but they turned out to be great listeners, far better than those in Japan. I sometimes think the audience with intellectuality and the knowledge often try to understand in a preoccupied mode and never empathize with music itself. If you are preoccupied with a concept or another, it could become a barrier.

The audience here were barrier free and accepted my music well. I consciously present the brief historical background of music. I hardly talk about the instruments in relationship to the Zen Buddhism as the tool for practicing monks to preach or to meditate. I have played a lot for meditation sessions, such as Tibetan Buddhist groups.

Generally speaking, I seem to have found a niche for myself in interacting and sharing with the audience. I offered two workshops to local Japanese language school kids and to its adult class last weekend and rediscovered myself in a comfort zone.

I am embarrassed to admit that I own a shakuhachi flute that I brought off a friend in Japan. It has been sitting on my bookshelf now for years.

Since you tell me you have a shakuhachi, I decided you don’t know enough about maintaining it in good condition. It’s the nature of bamboo, in that keeping it from the heat and the dryness is essential. Particularly in winter, if you use the electric baseboard heating systems, your indoor humidity is much less than you think.

The best maintenance is to play everyday, which constantly keep the moisture at a reasonable level. Otherwise, keep it wrapped with a piece of wet cloth. Avoid direct contact with the instrument. The fireplace in the room is no good either. I have eight professional instruments coming in different length and range of sound. I bought a wine rack to place all of them. The rack is placed right on a water-filled container and covered by plastic—I only play two or three shakuhachi daily. The instruments I do not use on a daily basis are in the rack when not used.

The ones always played don’t need my attention—enough humidity is maintained. I cracked two shakuhachis since I came here. It is also extremely important to unwrap and expose them in the air once a month or so to avoid moulding. The moisture should be at a reasonable level and not too humid. It may be just an instrument to some people and replaceable if/when broken. I don’t agree to that approach as a shakuhachi player, knowing how much of the maker’s spirit and effort is put into it. I’d say this after breaking two shakuhachis.

Was it difficult to maintain a career at Tonari Gumi and be a shakuhachi player?

I never could have accomplished that there in Japan. Clearly and precisely, I abandoned a-sort-of high-profile systems engineering career because of the reality that I could not play shakuhachi at my desired level if I would have stayed with the company any longer.

The place you live and teach sounds familiar. Jun (Samuel) Hamada, the Tonari-Gumi founder and my partner in the beginning, was from Brampton. I once visited his parents in 1977. I drove out after the concert of the Nikka Dancers in Toronto. I was one of the three musicians to tour with them across the country.

What does being Japanese mean to you now after so many years here?

A tough question to answer. Born, educated, and lived in Japan for 30 years, I do realize now, beyond all doubt, some positive effects and influence on my life here. One such example is their traditional way of living in a community, where reciprocal trust and mutual help was of prime importance. You become more sensitive and appreciative to co-exist with others in peace and harmony. A part of my personality nurtured in Japan allowed me to understand and work with our Issei seniors without much difficulty. I was able to relate to their social and cultural values, and probably was ready for working with them. In other words, I may have been a good fit to be a JC community worker.

What then does it mean to you to be Canadian?

This is even harder to answer. I think my 40 years here in Canada have been an on-going process of adaptation and integration into Canada’s multicultural society. I don’t feel, however, drastic changes have happened inside me. I don’t expect further changes nor much adjustment to my way of living would occur in the future, now that I have reached the age of 71. Nonetheless, I do appreciate the fact that the individual’s rights are enshrined in the Charter of Rights.

Finally, then, what are your hopes for the Canadian Nikkei community?

Today, we have the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre (in Burnaby, B.C.) where they are busy working on research and collections of historical artifacts and archival materials through the exhibits under their developmental projects. Their collections only get richer as they dig further into our preceding generations and their lives in Canada. Accordingly, it gets easier for our upcoming generations to access resources for our ancestral history of immigration and their lives through the building and development of the JC community.

As our community in future will be changing in its racial makeup and cultural values, I feel personally an urgent need of re-examination/re-evaluation on our future community needs and set a direction as to where to and how we are going. It seems to be a big challenge but we really should be talking about a multilingual and multicultural community within the JC community after all—bravo!

We all live as equal members in Canada’s cultural mosaic. Hopefully, this is when one may want to seek his/her identity with their conscious effort by going through to their ancestral roots. It will add much deeper and meaningful respect and confidence to his/her own dignity as a person. It may also give one an opportunity to appreciate their cultural heritage which they can then pass on to future generations.

© 2014 Norm Ibuki