The most fitting way I can think of to begin this review of Mary Adams Urashima’s Historic Wintersburg in Huntington Beach, is to appropriate and slightly modify what the great American poet Walt Whitman said in relation to his most notable poetic volume, Leaves of Grass (1855): “Whoever touches this book touches a (wo)man.” A resident of Orange County’s Huntington Beach and a passionate advocate of historic preservation, the perfervid desire of Urashima to preserve significant historical structures and sites derives not from her being a fusty antiquarian, but rather from her envisioning preservation as a progressive means to stimulate greater appreciation of America’s diverse history and cultures.

This cosmopolitan goal championed by Urashima, a California Association of Human Relations Civil Rights Leadership Award recipient, is personified in her book’s poignant dedication: “For my son, Keane Patrick Yoshio Urashima, in whose eyes I see the future.” In Orange County, that future promises to be one in which Asian Americans figure prominently, since 600,000 of the county’s present total of 3 million people are of Asian ancestry, placing the pan-Asian population of Orange County ahead of every other U.S. county save those of Los Angeles and Santa Clara. This demographic fact positions Orange County for a strategic leadership role in facilitating the nationwide initiative issued in 2013 by the Secretary of the Interior and the National Park Service to undertake an Asian American Pacific Island Theme Study tasked with investigating the stories, places, and people of Asian American and Pacific Island heritage.

At the heart of Urashima’s bountiful book is her engagingly composed, resourcefully documented, and marvelously illustrated story of a four-and-a-half acre parcel of land situated within the onetime agricultural village of Wintersburg, which flourished from the late 1800s until annexation in 1957 by suburbanizing Huntington Beach. It is Orange County’s only known pre-Alien Land Law of 1913 property still extant.

Owned by the pioneering Japanese American Furuta family, this site during the 1908-1947 interval became populated by a complex of six historic structures that, in 2014, are still intact: 1) the 1910 Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Mission (Orange County’s oldest Nikkei church, it was founded in 1904); 2) the 1910 manse, home to Orange County’s first ordained clergy of any denomination; 3) the 1912 home of Charles Mitsuji and Yukiko Yajima Furuta; 4) the 1908-1912 Furuta barn, Huntington Beach’s last pioneer heritage barn; 5) the 1934 Depression-era Wintersburg Japanese Presbyterian Church; and 6) the 1947 post-World War II home of Raymond and Martha Furuta.

This piece of property, which includes remnants of a goldfish and flower farm, topped the list of the dwindling few remaining Nikkei sites of importance compiled in 1986 by the Japanese American Council of the Historical and Cultural Foundation of Orange County. Capitalizing on the JAC-sponsored oral history interviews with four pioneering Issei (Japanese/English) and one Nisei (English only) revolving largely around the historic Wintersburg site, Urashima fashions a compelling argument to support the contention by historians (including myself) that this site, in tandem with a cluster of nearby commercial and public-use facilities, should properly be considered the cradle of Orange County’s loosely aggregated—i.e., the county has never had a Japantown—community.

However, in 2011, Urashima and others (in and out of Huntington Beach and the Japanese American community) became alarmed when the city of Huntington Beach, which in 1996 had listed the “Furuta House” and “Japanese Church” as local landmarks in its Historic Resources Cultural Element of the City’s General Plan, now issued an ominous notice. It was for an environmental impact report on behalf of the historic site’s then owner, Rainbow Environmental Services (a waste transfer company, aka Rainbow Disposal), which proposed a zone change from residential to industrial/commercial with an application for demolition of all site structures. At that point, Urashima mobilized a community-wide effort, which she has since chaired, to preserve “Historic Wintersburg.” She also initiated an ambitious, highly imaginative, and exceedingly far-reaching “Historic Wintersburg” blog. Her book, which is rooted in but does not replicate this blog, should be seen therefore not as just another local history volume, but instead as the creation of a person of enlarged consciousness and conscience who has employed history as a social and moral force.

On November 4, 2013, the Huntington Beach City Council, by a split vote, duly rezoned the Historic Wintersburg property and approved the demolition of all six of its historic structures. The City Council did give the Historic Wintersburg Preservation Task Force 18 months (until mid-2015) to save this historic site. On June 23, 2014, the National Trust for Historic Preservation named Historic Wintersburg to its 2014 list of “America’s 11 Most Endangered Historic Places.” It is the first historic place in development-oriented Orange County so designated in the 27-year history of the NTHP list. Preservation of Historic Wintersburg remains a long shot, but that contingency assuredly will not deter Mary F. Adams Urashima from trying to salvage this priceless historical and cultural site. Those of you who read her absorbing blog and/or book will, I think, fathom why Historic Wintersburg is worth saving and perhaps even elect to assist in its preservation for posterity.

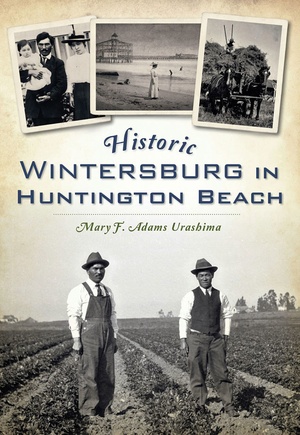

HISTORIC WINTERSBURG IN HUNTINGTON BEACH

By Mary F. Adams Urashima

(Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2014, 208 pp., $19.99, paperback)

*This article was originally published on Nichi Bei Weekly, on July 24, 2014.

© 2014 Arthur A. Hansen / Nichi Bei Weekly