As with most people who subscribe to cable television, I suffer through an endless number of inconveniences, indignities, and monetary insults. When the signal becomes sporadic or even fails, I call and get a recording that tells me to unplug my box and let it reboot, which seems like the kind of tech support that my long-deceased Issei grandparents could have figured out. (My grandmother, for instance, referred to their automobile, in her halting English, as “the machine.”) Cable gets more expensive every year, but they compensate by making the customer service worse and worse. But, since I have Time Warner and I want to watch the Dodgers, I endure.

Among the potential benefits of cable, however, are the hundreds of stations carrying all sorts of programming. If you are my age or younger, there is probably a station delivering old TV programs you watched fondly when you were growing up.

Recently, I saw an episode of the 1960s comedy, Get Smart, which brought up the question: how I should view programs that I used to enjoy, but suffer from anachronistic stereotypes? I was in junior high school when Get Smart first aired and I still remember the pilot in 1965 (I think it might have been filmed in black and white), introducing Maxwell Smart, Agent 86. The show, conceived by Mel Brooks and Buck Henry, was a satire of both James Bond and the very popular Man from UNCLE television show. The key to the success of Get Smart was its star, comedian Don Adams, who had introduced a similar bumbling, slow-witted hotel detective, Byron Glick, on The Bill Dana Show (speaking of stereotypes, remember Jose Jimenez?). Adams was perfectly cast as Smart and I remember laughing out loud at the pilot, which introduced one of the show’s most famous catch phrases, “Would you believe…?”

Anyway, I found some obscure station broadcasting Get Smart after midnight and watched part of the episode that introduced the character Harry Hoo. Anyone my age will immediately understand that this was a takeoff on the famous Charlie Chan mystery books by Earl Derr Biggers and, more directly, the dozens of movies made prior to and just after World War II. While Biggers based Charlie Chan on a real Honolulu Police Department detective named Apana (Ah Ping) Chang, the movies are famous (or infamous) for having the Chinese American solver-of-mysteries portrayed by various Caucasian actors such as Warner Oland, Sidney Toler, and Roland Winters. While Biggers’ intent in developing Charlie Chan was to create a positive Chinese American character, who was smart, dedicated, and a force for good, the fact that all the movies refused to cast a real Asian American actor in the lead role was a not-so-subtle undermining of that notion. In contrast, the movies included two of Chan’s scions (No. 1 Son and No. 2 Son, played by real Asian Americans, Keye Luke and Victor Sen Yung) whose function was basically comedy relief. The real Chinese guys, the casting suggested, were boobs and the white guy playing Charlie Chan was actually the hero.

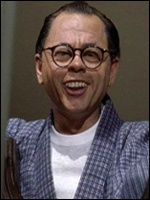

On Get Smart, comedian Joey Foreman portrayed Hoo with the standard Charlie Chan accent in two episodes. (FYI, real life detective Chang was actually born in Honolulu, but moved to China when he was 3, only to return at age 10. Legend has it that Chang could speak Chinese, pidgin, and other languages common to Hawai`i, which helped in his efforts to solve crimes.) The comedy comes from Hoo’s surprise at Smart’s overall incompetence and general density, to which he responds by remarking, “Amazing.”

I thought the episode was funny in the 1960s and I still find it amusing today, but it is a basic guilty pleasure. Intellectually, I know what is most objectionable then and even today is the idea that an Asian or Asian American actor could not handle the role, especially since it was based on a real Chinese American. Whether it is David Carradine as the lead character in TV’s Kung Fu (a part Bruce Lee was up for! Bruce Lee!) or Jonathan Pryce playing the Engineer in Broadway’s Miss Saigon, the main complaint is that actual Asians and Asian Americans were being shutout of the primary roles of movies, television shows, and stage productions for most of the 20th Century.

The usual retort is that an acting role should be performed by anyone who is capable. The real issue for Asians and Asian Americans is that the reverse has not been true for them. For most of my lifetime, I rarely recall Asian or Asian American actors being cast in roles not specifically written for Asians or Asian Americans. The other demeaning movie gimmick that undermines fairness is the casting of Asian and Asian Americans in supporting roles while bringing in a non-Asian movie actor as the star. Consider Tom Cruise in The Last Samurai (Wait a minute—everyone else was killed but Tom Cruise?!!) or Dennis Quaid in Come See the Paradise (I actually liked a lot of this movie, but Quaid’s character was unnecessary.) That is why John Korty’s adaptation of Farewell to Manzanar (1976) is so exceptional, since it features Asian Americans in the leading roles and refuses to insert extraneous non-Asian characters into the story about Japanese Americans. Sam Fuller’s Crimson Kimono (1958) is the other standout, casting James Shigeta as a romantic lead who gets the (white) girl, a total movie taboo in the 1950s.

Today, Lucy Liu is able to portray Dr. Watson to Jonny Lee Miller’s Sherlock Holmes in CBS’ Elementary and John Cho can be the Henry Higgins’ character to Karen Gillan’s Eliza in ABC’s Selfie. But how should we view almost a century of anti-Asian attitudes, from major crimes to misdemeanors?

I don’t have a definitive answer since I can’t possibly formulate a response that works for everyone. For me, I have a basic approach that can be seen by comparing two major motion pictures from the post-war: Teahouse of the August Moon (1956) and Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961). Both films were derived from books and both were well received by the critics. Both have white actors playing Japanese nationals and both use makeup to provide them with their “Asian” look, but the portrayals are quite different.

In Teahouse, Marlon Brando, having just won an Academy Award for his performance in On the Waterfront (1954), plays a rather large Okinawan interpreter named Sakini. Teahouse of the August Moon had been a successful Broadway stage comedy, winning a Pulitzer Prize and a Tony Award in 1953, so it is not surprising Hollywood wanted to transform it into a film. The story, adapted by John Patrick for the stage and the film from a 1951 novel by Vern Sneider, is a comedic look at the U.S. Occupation Forces trying to convert the people of Tobiki, Okinawa, to American-style democracy. The protagonist, Captain Fisby (played amiably by Glenn Ford), is ordered to bring about Americanization by his superior officer, Col. Wainwright (Paul Ford, no relation to Glenn, perfectly embodying the overblown bureaucrat), but he needs an interpreter, Sakini (Brando). As with so many film comedies of this nature, the seemingly more sophisticated and well-educated Fisby is no match for the supposedly hick locals. He eventually embraces Okinawan values instead of the other way around. For instance, Fisby is directed by Wainwright to build a new schoolhouse in the shape of the Pentagon, but the Okinawans want a teahouse and eventually Fisby agrees.

The core question: what to make of Brando’s casting as Sakini? Brando was in his prime film acting years in the 1950s and he reportedly devoted two months to studying Okinawan culture, speech, and even gestures. He also spent two hours each day prior to filming to having makeup applied to give him an Asian look (although if you watch the film, he looks more hapa than full Japanese). Because of his size, Brando seems to play Sakini bent over so he doesn’t tower over Glenn Ford. At the time, less than discerning audience members complained upon seeing Teahouse, because they expected Brando and never saw him. Critic Pauline Kael wrote, “Marlon Brando starved himself to play the pixie interpreter Sakini, and he looks as if he’s enjoying the stunt—talking with a mad accent, grinning boyishly, bending forward, and doing tricky movements with his legs. He’s harmlessly genial (and he is certainly missed when he’s off screen), though the fey, roguish role doesn’t allow him to do what he’s great at and it’s possible that he’s less effective in it than a lesser actor might have been.”

I personally had trouble with Teahouse for many years because the idea that even a great actor like Brando would take the role of an Asian man was too disturbing for me to watch the film with any enjoyment. “Yellowface” was akin to white actors doing minstrel shows with black makeup. As I have gotten older, I tend to view Brando’s casting as a venial sin. By all accounts, Teahouse (both the play and the movie) was a progressive vehicle for its time that presented the people of Okinawa in a sympathetic, if not realistic, light. Considering the war ended just a decade before and incited the highest levels of racism against all things Japanese, Teahouse probably did considerable good. Brando’s portrayal of Sakini is silly, but, to me, not outright disrespectful to Okinawans.

Breakfast at Tiffany’s is a different animal. A romantic comedy, the film stars Audrey Hepburn as Holly Golightly, a New York society girl, who has abandoned her Southern past, including her name and teenage marriage to an older man. The movie is loosely based on a novella by Truman Capote and made Hepburn into a mega-star in the 1960s. Holly benefits by keeping company with wealthy older men, but is not a prostitute. (Interestingly, Teahouse tries to make the point that Lotus Blossom is a geisha and not a prostitute as well.) The film is littered with quirky characters and a strong cast (Patricia O’Neal, Martin Balsam, Buddy Ebsen), but the story swings on Holly’s relationship with Paul (George Peppard), who is something of a writer/gigolo. Hepburn’s presence makes the movie work, which is why its main defect seems so out of place.

Mickey Rooney, who was once one of the country’s biggest movie stars before the war, plays photographer I.Y. Yunioshi, Holly’s upstairs neighbor. Rooney wore a prosthetic mouthpiece and makeup that makes him resemble the worst racist caricature cartoons from World War II. Director Blake Edwards apparently wanted Rooney to do the role and go over the top with his performance. It is so bad that, decades later, producer Richard Shepherd has repeatedly apologized and Edwards himself stated, “Looking back, I wish I had never done it…and I would give anything to be able to recast it, but it's there, and onward and upward.” Even Rooney expressed regret, although he insisted after 40 years, “not one complaint.” He sort of issued the non-apology apology. (You know, “I’m sorry if anyone was offended” which translates to “I’m sorry you are so stupid, because, God knows, I didn’t do anything wrong.”)

This is the prime example of a cardinal sin and, to me, makes Breakfast unwatchable. At least with the Charlie Chan novels and Teahouse, I have a sense that the creators were seeking to create some positive images. Clearly, the Yunioshi character in Breakfast was the height of racial ignorance (although Shepherd apparently wanted a real Japanese actor, but Edwards insisted on Rooney) and I don’t find him funny. At all. It’s hard to feel good about the rest of the movie, which is clearly well done. Hepburn was nominated for an Academy Award and she sings Henry Mancini’s “Moon River,” which won an Oscar.

If I want to watch Audrey Hepburn, I’ll watch her in Charade with Cary Grant. I will watch Get Smart reruns and have a laugh at Harry Hoo and “The Claw” when no one else is around. But I will also remember the historic context and I hope everyone else does, too.

© 2014 Chris Komai