The Japanese Pavilion in Ibirapuera Park, known as the "Central Park of São Paulo," held a ceremony to celebrate its 60th anniversary on August 29th, welcoming the 15th head of the Urasenke school of tea ceremony, Sen Genshitsu, and others from Japan. The building was designed to resemble the Katsura Imperial Villa, and is rare in the world as a "purely Japanese" building, with pillars, roofing tiles, and even gravel brought from Japan.

The Japan Pavilion embodies the universality of Japanese culture

The man who made this happen was Yamamoto Kiyoshiji (1892-1963, Tokyo), manager of Higashiyama Farm, which still exists today in Campinas, São Paulo. After the war, Yamamoto served as the representative of the Japanese Cooperation Committee for the 400th anniversary of the founding of São Paulo (1954), which was organized by the city of São Paulo, and through the founding of the São Paulo Japanese Cultural Association (1955, now the Brazilian Japanese Cultural Welfare Association), a central organization for the Japanese community that was created by dissolving that committee in a progressive manner, he is generally known in the Japanese community as the man who achieved the integration of the Japanese community, which had been divided in two by the "win-lose conflict" immediately after the end of the war.

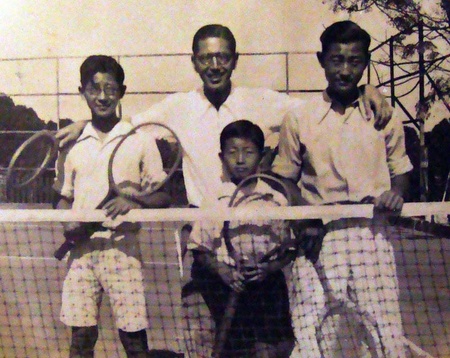

I visited Yamamoto's second son, Carlos Tan (88, born in Beijing), at his home in late June 2012 and asked him about his relationship with Akutagawa Ryunosuke during their time in Tokyo.

Horiguchi Sutemi, who designed the Japan Pavilion, also attended the University of Tokyo as Yamamoto. Yamamoto graduated from the Faculty of Agriculture in 1917, while Horiguchi graduated from the Faculty of Engineering in 1920, so they were juniors from different departments. Horiguchi was strongly influenced by the new European architectural styles, and while searching for how to confront them as a "Japanese architect," he came to consider sukiya-zukuri to be the "essence of Japanese architecture."

Therefore, the Japanese Pavilion is modeled after Katsura Imperial Villa, a representative example of a similar style, and is said to be one of Horiguchi's masterpieces. He did not simply return to tradition, but sought "universality" that would be applicable to the modern era.

"Japan realized the aesthetics of asymmetry that Europe only just became aware of in the 20th century, with the Sukiya-style architecture hundreds of years ago, meaning that they were ahead of the curve" (INAX Report No. 186, p. 4). This is exactly what the Japanese community is trying to do by finding universality in Japanese culture and trying to implant it in Brazil.

Graduated from Tokyo University, traveled to Manchuria and went to Brazil

After graduating from the Faculty of Agriculture at the University of Tokyo, Yamamoto joined Mitsubishi and learned about livestock farming at Koiwai Farm. He then moved his family to Beijing to manage the farms that Higashiyama Nojisha was developing in China and other countries. He imported cotton from North America and worked mainly on cotton improvement and cultivation, living there for a total of seven years.

Of the four children, only the eldest daughter, Yoko, was born in Japan, while the next two sons (Miki and Tan) were born in Beijing, and the last son, Jun, was born in Brazil, making them a truly international family even today.

In October 1926, Yamamoto traveled to Brazil alone to purchase Higashiyama Farm, and brought his family over the following year. Higashiyama Farm is managed by Higashiyama Noji Co., Ltd. (headquartered in Tokyo), run by the Iwasaki family. President Hisaya Iwasaki (the eldest son of the company's founder, Yataro Iwasaki) had complete confidence in Kiyoshi Yamamoto.

Tan remembers that "Iwasaki Hisaya was very concerned about Japanese immigrants, and that Brazil's agriculture was limited to sugar cane and coffee, and that it would eventually suffer if international prices collapsed. So he asked my father to create an experimental farm that would increase the variety of crops and spread agricultural techniques, not for the sake of making money."

It is said that Yamamoto was concerned about the large number of Japanese immigrants who were damaging their health by drinking too much pinga (a cheap, high-alcohol liquor made from sugar cane), and so he decided to brew Brazil's first sake, Azuma Kirin.

Tan says, "My father originally came here only to stay temporarily to help manage the farm." Yamamoto quickly became fluent in Portuguese, thanks to a Brazilian teacher, and developed friendships with the scholars and executives of the Campinas Agricultural Research Institute, one of the region's leading research institutions. He liked the place. However, what made Yamamoto decide to stay permanently was the death of his eldest daughter, Utako, from typhoid in March 1930, four years after arriving in Brazil.

President Vargas' feud with Japanese immigrants

In 1930, Zettlío Vargas launched a revolution, took power, and suspended the Republic Constitution. The state of São Paulo, an emerging power centered on the coffee industry, launched a constitutional revolution against President Vargas in Rio in 1932 under the slogan "Protect the Constitution," but was defeated by the federal army within three months. Higashiyama Farm was one of the final battlegrounds.

President Vargas became a dictator in 1937 and promoted nationalistic policies, remaining in power until the end of 1945. He fostered a national identity by promoting samba as Brazil's unique national music and nurturing soccer as the national sport. In the industrial sector, he also started a steel business, established important institutions such as Petrobras (the state oil corporation), and established modern labor laws, making him an important figure who is said to have "built the framework for the nation."

During the war, Vargas was caught up in the aggressive foreign policy of the United States, sending the Brazilian Expeditionary Force to the European front and is also known for persecuting Axis immigrants in the country. As a result, the assets of major Japanese companies and large farms run by immigrants, including Higashiyama Farm, were frozen. However, after the war ended, the military forced him to resign and drove him out.

The persecution during the period leading up to and after the war caused strong psychological stress to Japanese immigrants, instilling in them the obsession that "Japan cannot lose." At the end of the war, when the question of whether to accept defeat arose, most of the immigrants who thought "we cannot lose" became "winners," and ended up in conflict with the "losers" they had accepted, leading to killing each other, leaving a negative impression on Brazilian society.

Yamamoto thought that the only way to reconcile the Japanese community was to find something that both sides could do together. At first, it seemed that a campaign to send "LARA supplies" to help the homeland would be the answer, but it drew backlash from the winners and did not lead to reconciliation. Tan recalls, "My father thought of something that both the winners and losers could do together, and began preparations for the 400th anniversary of the city of São Paulo."

He continues, "Italian and German immigrants, as well as those from the UK and the US, have built pavilions in Ibirapuera Park, but Japan is the only one with a permanent pavilion. My father thought, 'It will take time to integrate the Japanese community. Unless we create something impressive that will be remembered for future generations, we will never be able to dispel the bad image that has spread through the struggle for victory and defeat.'"

The indomitable Vargas was democratically re-elected as president in the 1950 presidential election. The Japanese Pavilion was topped out in May 1954, and was completed on August 31. On August 24, one week before the opening, President Vargas, who had caused suffering to Japanese immigrants during the war, had committed suicide, unable to bear the pressure from his political opponents.

In December of the year following the construction of the Japan Pavilion, the Japan Cooperation Committee was dissolved and the Sao Paulo Japanese Cultural Association was established as the central organization of the Japanese community. In 1958, on the 50th anniversary of their immigration, Prince and Princess Mikasa came to Brazil, and they worked hard to integrate the Japanese community. They also pushed ahead with the construction of the Bunkyo Building, which seemed to shorten the life of the association.

His passionate friendship with Akutagawa could be likened to homosexuality.

In fact, the wife of the literary giant Ryunosuke Akutagawa was the daughter of Yamamoto's sister, and the two were also old friends since their days at Tokyo Prefectural Third Junior High School. They exchanged about 80 letters. According to Tan, before his death, he told his family, "Please burn these letters after I die."

In 1954, when Soichi Oya made a special visit to Yamamoto's residence in Hijiri and asked to see the letters, he declined. Tan recalls, "My father always exchanged letters with Akutagawa, but my mother was afraid of him, saying that he was 'too smart.'"

The monthly magazine Bosho (Tokai Educational Research Institute, August 2007 issue) contains a surprising article entitled "Special Feature - Akutagawa Ryunosuke's 'Letters'": Yamamoto and Akutagawa had a passionate friendship that could be likened to homosexuality when they were both students at First Higher School. On page 33, from a letter sent by Akutagawa, the following candid words of youth, typical of a great young writer, are introduced: "I live because of you, and if I could be with you, I believe that even death would be sweet."

The special feature also includes an interview with Japan-based illustrator Nagao Minoru, who stayed in Brazil for three years from 1953 and assisted Yamamoto Kiyoshi with his work, revealing some interesting anecdotes he heard directly from Yamamoto.

Yamamoto is said to have also given advice to Akutagawa on his writing activities.

"Akutagawa had said that his works did not make him money, and that he felt sorry for his family after he died. So they asked each other what to do, and they came up with a plan together...Yamamoto said that, analysing examples of European literature, there are certain conditions that must be met for works to be remembered for future generations, so he suggested that they derive such an equation and follow it exactly, and together they worked it out, and Akutagawa actually did just that" (ibid., p. 25).

When Yamamoto died in 1963, for some reason the letters were not burned, but instead, in response to an inquiry from a Japanese researcher, his family sent all of them, revealing the extent of their close relationship.

What if Akutagawa had come to Brazil?

In "Yamamoto Kiyoshi Biography" (Sao Paulo Institute of Humanities, 1981, p. 18), it is written that "Yamamoto's dream from the beginning was to invite Akutagawa to Brazil and revive his weakened body and mind under the vast nature, clean air, and intense tropical sun." This is a typical wish of Yamamoto, who was well aware of Akutagawa's tendency to become mentally unstable, but unfortunately it did not come to fruition.

Yamamoto may have wanted Akutagawa to write something about Brazil. Akutagawa committed suicide by taking poison in July 1927 at the young age of 36. If we look closely at the timeline, this was the year after Yamamoto traveled to Brazil. If he had been successful in inviting Akutagawa to Brazil, he might not have committed suicide. And he might have written a masterpiece set at Higashiyama Farm in the final stages of the 1930 Constitutional Revolution.

Coincidentally, Ishikawa Tatsuzo's novel Soumang (Soumang), which describes Ishikawa's experience traveling to Brazil on an immigrant ship in 1930, won the first Akutagawa Prize in 1935. Akutagawa in heaven may have been the one who was most pleased that a novel on the theme of immigration had won a prize named after him.

Yamamoto, who smoked four packs a day, died of lung cancer on July 31, 1963. Yamamoto was the president of the Bunkyo Association and at the time was also the head of the Brazilian branch of the Urasenke tea ceremony. Bedridden since April of that year, Yamamoto called for the deputy head of the branch, Hachiya Sen'ichi, about ten days before his death. Although Yamamoto was supposed to be bedridden, for some reason he had changed into a kimono and was waiting in seiza position, saying, "If you take over from here on out, I can pass away in peace" (Yamamoto Kiyoshi Biography, Jinbunken, 1981, p. 62). He was a man who knew when it was time to die.

"I'm the only one who can talk about my father as someone close to me now. Most of what I've said today was only known by my family," Tan added, concluding the conversation.

Yamamoto worked hard to make the Japan Pavilion a reality, and Noriyuki Nakajima, president of Nakajima Construction (head office in Gifu), who was inspired by Horiguchi's vision for the Japan Pavilion, has brought in carpenters at his own expense to carry out repairs at each milestone anniversary since the 80th anniversary of Japanese immigration to the country (1988), the 90th anniversary, and last year's 105th anniversary.

© 2014 Masayuki Fukawasa