Sport has played a major role in the life of Japanese American communities from the first establishment of those communities in the late nineteenth century to the present. Over time, that role has changed. For the immigrant and first American-born generations, participation in sports was seen as a step towards “Americanization,” while at the same time it served to cement ties within the community.

Although outstanding Japanese American athletes have met many discriminatory barriers, many, when given the opportunity, have managed to reach the highest levels of their sports and their exploits have been eagerly followed by the community. And the continuing existence of Japanese American community sports leagues today contributes in no small way to the persistence of Japanese American communities and ethnicity.

SUMO, BASEBALL, AND THE ISSEI

From 1885 to 1924, Japanese subjects migrated from their home country to the United States and to Hawai‘i as part of a larger diaspora, fueled by a lack of economic opportunity in modern Japan, a burgeoning population, and a need for labor in the host countries. These early Japanese migrants came to work on Hawai‘i’s sugar plantation and later, on the railroads, sawmills, mines, and farms of the western United States. Their lives were difficult, filled with rough physical labor, irregular and seasonal employment, and the sting of racial prejudice. But like many other immigrant groups, the Issei persevered, building families and communities and establishing a place for themselves in their new home.

Though work and family life took up much of their time, there was still some time for fun. At holiday picnics and other community celebrations or ceremonial occasions, sporting activities often played a central role. For the Issei, the two sports which emerged as most popular were sumo and baseball.

Sumo “crazes” were kicked off by visits of prominent Japanese sumotori (sumo wrestlers) to both Hawai‘i and mainland Japanese American communities in the first decade of the 1900s. Soon Issei and Nisei alike were taking up the sport. Tournaments were held to commemorate important occasions, ranging from the Emperor’s birthday to the 4th of July.

Toyomori Hosokawa became one of the leading sumotori of the Issei era upon his arrival to the United States in 1924. He settled in the Sacramento Delta area and established himself by winning numerous tournaments and representing his community in competitions with other regions, battling under the name “Toshuzan.” (Leading sumo performers were customarily given special sumo names by officials.) His sudden and untimely death from pneumonia in 1930 inspired a memorial tournament drawing the top stars of the area.

Meanwhile, at about the time Japanese immigrants were migrating to the U.S., baseball was gaining immense popularity in Japan. Given its popularity in America as well and its status as the “National Pastime,” it was natural that many Issei would become serious players, coaches, or followers of baseball. By the first decades of the 20th century, Japanese American baseball teams and leagues had formed throughout the West Coast and Hawai‘i.

One Issei who became renowned for his love of baseball was Kenichi Zenimura of Fresno standing just five feet tall and weighing 105 pounds, he became a leading player in Fresno in the 1920s, playing shortstop for a local team. Later, he would become a key figure in organizing tours of Japanese American teams to Japan starting from 1924 and organizing baseball teams in the American concentration camps of World War II.

Some Issei gained a degree of notoriety in other kinds of sporting activity. For instance, Jujiro Wada of Alaska became a champion marathoner and a legendary figure in the sport of dog sled racing, while other Issei took up everything from kyudo (Japanese archery) to football.

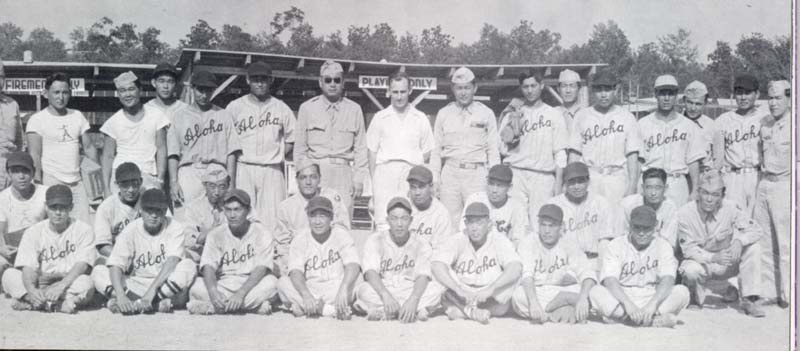

The legendary 100th Battalion formed a baseball team which played various local teams in the places where they were trained. In June 1943, while training in Camp Shelby, Mississippi, they journeyed to Jerome “Relocation Center” to play a team of Nisei interned where this picture was taken. Joe Takata, the first 100th member to be killed in action, is in the front row, at the far right. Gift of the Tagami Family (formerly of White Point) (89.17.2A)

SPORT AND THE NISEI PROBLEM

After the Gentlemen’s Agreement of 1907-08 closed off the migration of Japanese laborers to America, large numbers of Japanese women began to immigrate, exploiting a loophole in the law. The arrival of women led to the formation of families. From the 1920s to the 1930s large numbers of Nisei, the first American-born generation, were born.

The Ozawa Supreme Court decision in 1922 (upholding the ban on naturalization for Issei), the upholding of Alien Land Laws in 1923 (banning Issei from purchasing agricultural land) and the closing off of further Japanese immigration in 1924, effectively set the limits on Issei life in America. Hope for the future of the Japanese American community turned to the Nisei.

But what kind of future would it be? Would the Nisei, born with the American citizenship Issei could never hope to have, be able to overcome the existing prejudices to live a full life in America? Or was racism so deep-seated, that the future of the Nisei generation was in Japan and other parts of the ever-expanding Japanese empire? Or was it somewhere in between?

Sport became one arena where the “Nisei problem” played itself out.

Many Nisei participated in sumo tournaments and took up other “Japanese” sports such as judo or kendo as children in the 1920s and 30s. Their Issei parents undoubtedly encouraged such activity in part to keep their children busy and out of trouble. But they surely also wanted to children to associate with other Nisei children and to learn something about “Japanese” culture.

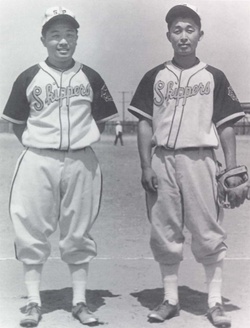

The San Pedro Skippers were one of the outstanding Nisei teams of the 1930s. Pictured are two of the Skippers stars, Cy Yuguchi, left and Isamu “Pee Wee” Tsuda. Photo by Frank M. Murakami. Collection of Kenji Yamamoto (96.241.4)

In the mid to late 1930s, a rise in Japanese nationalism could be detected in Japanese immigrant communities. This nationalism was due in part to the continuing racism and diminishing opportunities in America, the rise in Japanese militarism in Asia, and a romantic longing among the Issei for the home country.

In the 1920s and 30s, sumo and kendo became vehicles for increasing awareness and association with Japan among participating Nisei youth. Top Japanese sumotori came to America to demonstrate the latest techniques, while younger sumotori competed against their Nisei peers. Nisei sumo and kendo groups traveled to Japan, sponsored by leading Issei businessmen and associations. Perhaps inevitably, Japanese nationalism crept into these sporting endeavors.

Several Nisei pursued professional careers in sumo prior to the war. The first was Sadaji Fukuyama (“Fukunishiki”) of Sacramento, who went to Japan in 1934. He was called back by his father when he turned twenty-one, in large part to avoid being drafted into the Japanese military. The most successful of the Nisei sumotori in Japan was Harley Ozaki (“Toyonishiki”) of Colorado who achieved sekitori (to gain a ranking in one of the top two divisions of professional sumo) status, becoming the first foreigner to do so.

Nisei also played baseball, basketball, and other American sports mostly in segregated leagues from the 1920s. Though Issei and Nisei disagreed on many things, such sporting activity was one area where there was an agreement–if for completely different reasons. For Nisei, eager to be as American as the next kid, baseball was a way to assert their “American-ness” and to excel in an area where one rose or fell on the basis of his ability, not his skin color. For Issei, the segregated nature of the leagues insured that their children would be interacting with other Nisei and would meet peers from other Japanese American communities in other parts of the country. Some Nisei baseball teams also traveled to Japan.

Not all Nisei played in segregated leagues. In areas where there were either very few or a great many Japanese Americans, some Nisei played in mixed leagues. In Washington, the Wapato Nippon, an all-Japanese American baseball team, played in a league with non-Japanese American teams. Outstanding teams became points of pride for their communities. Whether segregated or not, baseball took root throughout every corner of Japanese America.

The Konawaena High School girls’ baskeball team, the “Island Basketball Champions.” Kealakekua, Kona, Hawai‘i, 1926. Collection of Shigeru Akamatsu (94.227.2)

And it was not just men and boys who played. From early on, basketball and softball leagues for Nisei women were also part of many Japanese American communities. In an era when vigorous sporting activity as deemed by the larger society as inimical to femininity, Japanese American women were playing ball with the approval of the leaders of the ethnic community.

*This article was originally published in the Japanese American National Museum Quarterly, Fall 1997.

© 1997 Japanese American National Museum