Read Part 1 >>

Wintersburg Village

By 1902, seventeen years after the first Japanese Presbyterian Mission was established in northern California, the Presbyterian and Methodist Evangelical churches in nearby Westminster had taken note of Orange County’s growing Japanese community. Rev. Inazawa was sent to investigate. By 1904, Rev. Inazawa and Rev. John Junzo Nakamura met with Rev. Terasawa, leading to the founding of the Wintersburg Mission.

At that time, there was no Presbytery established in Orange County. The Los Angeles Presbytery had no funds, leaving the Wintersburg Mission support to the local community. In an interfaith effort, nearby Presbyterian and Methodist congregations contributed, as did the Christian Endeavor Union of Orange County. Donations for the first chapel came from the surrounding farmland, including from some of Huntington Beach’s and Westminster’s prominent pioneer families.

Rev. Nakamura stayed on to oversee the building of the Mission and manse, with “the aid of our countrymen and some good American friends.”

Sturge attended the opening ceremony of the Wintersburg Mission on May 8, 1910, to see the work of his protégé, Rev. Inazawa, as did Rev. H.C. Cockrum of Westminster and five other local clergy. It was a large gathering for the little Wintersburg Village.

The opening ceremony for the Mission on May 8, 1910, with the manse to the left and in the background, the Terahata home that had been moved temporarily to the property. At the center of the crowd along then-country road Wintersburg Avenue can be seen Charles Furuta, on whose land the Mission stood, and Dr. E. A. Sturge. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) All rights reserved. ©

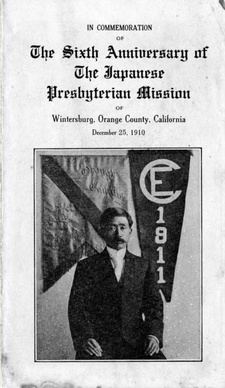

In a December 25, 1910 pamphlet marking the sixth anniversary of the Mission’s founding, Rev. Nakamura describes how he made the circuit in rural Orange County, a trip that today would take a day took a week to complete.

Japanese farmers on horseback at Irvine Ranch, Orange County, circa 1920. (Photograph snip courtesy of California State University Fullerton, Center for Oral and Public History PJA 497) All rights reserved. ©

“Last summer, I tried a fortnight’s campaign of gospel preaching, during which I traveled over two-hundred and twenty-five miles, visited forty families and camps, preached to four-hundred and fifty souls, distributed three-hundred and sixty copies of the Gospel of Matthew and sold eighteen copies of the New Testament,” writes Rev. Nakamura, who adds that he converted four souls.

Reverend John Junzo Nakamura with the Young Christian Endeavor Union banner. (Image courtesy of the Furuta family) All rights reserved. ©

Rev. Nakamura would have traveled by horseback through the farm fields, ranches, and open land to reach the scattered Japanese immigrants, riding through the tules of the peatlands.

His account also makes note of the annual Christian convention held in Huntington Beach in 1910, at which his group received the Orange County Christian Endeavor Union banner.

“It was entirely unexpected!” writes Rev. Nakamura, who adds that they shared a Thanksgiving meal with “a few American friends” in Orange County afterward. Although noting that “at present our Mission has no permanent resources,” he is encouraged they started with “fifteen active members, five associate members, and fifteen friends.”

Rev. Nakamura describes the mission field as including Wintersburg, Bolsa Beach, Smeltzer, Bolsa, Garden Grove, Old Newport, Talbert, and Huntington Beach. In 1910, he estimated there were about 300 Japanese permanently living in the area.

Japanese Missions in California

The Presbyterian Japanese Mission trail in California is joined by the early Methodist Evangelical, Episcopalian, congregational Japanese missions, and Japanese Buddhist temples established during the pioneer settlement period starting in the late 1800s. Most were established through interfaith efforts, community helping community. Not all have survived the politics and development of California.

As the United States entered World War I in 1917—and after 30 years working to establish Japanese missions in California—Sturge provided an update as part of the Annual Report of the Board of Foreign Missions to the national Presbyterian Church.

“About 90% of the 100,000 Japanese in the U.S. are on the Pacific Coast…there are 66 churches and missions belong to twelve denominations,” writes Sturge. “The work among the Japanese on the coast is carried on at San Francisco, Salinas, Watsonville, Los Angeles, Wintersburg, Hanford, Stockton, Sacramento, Monterey, Long Beach. There are 17 unorganized churches or groups and five organized churches…”

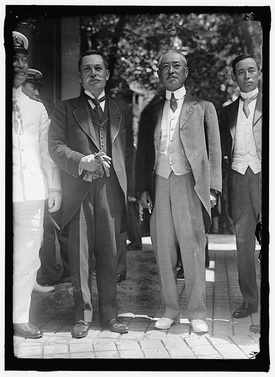

Viscount Kikujiro Ishii, second from left, visited the United States in 1917 on a special mission for the Imperial government of Japan. Despite California's passage of the Alien Land Law of 1913 and restrictions on immigration, Japan and the U.S. federal government worked to maintain relations on the Pacific Rim. (Photograph, Library of Congress)

This also was the year Viscount Kikujiro Ishii visited the United States on behalf of Japan, as part of a special mission to assure good relations with the United States. He stopped in San Francisco on his way to Washington, D.C., to meet with and address Californians, remarking on the hospitality he had been shown:

During the past three days I have been making what I believe you call in America a whirlwind campaign. Your kindness has been the whirlwind, and I and my colleagues have been the wind driven leaves. Fortunately, we are most of us young men still in the prime of life, and we are endeavoring to stand up as bravely as possible to the kindly blast. I am fully convinced, however, that the city of San Francisco, headed by its gallant Mayor, has entered into some kind of a conspiracy on this occasion to outdo its own worldwide reputation for hospitality; and when you remember that this conspiracy has been aided and abetted by the federal government of the United States and by the sovereign state of California, you will form some idea of what it means to stand directly in the path of the wind.

In response, California attorney Gavin McNab—who acted as toastmaster for the official state visit and was a member of President Woodrow Wilson’s industrial council—invoked the romance of California’s Franciscan missions, perhaps not realizing another California mission trail had taken root three decades earlier.

The gentle padres whose spiritual wanderings sanctified our soil built the quaint mission churches—a horseback ride apart—and the traveler was cared for without price; the Spanish Don, who measured his land by the league and not the acre, and whose cattle ranged a hundred hills, gave the stranger his house and all; the pioneer, who found the gold whose magic charm assembled here the greatest adventures from all the world, shared his plenty with all. Thus hospitality became a tradition of the West. But it is with more than hospitality that we greet these great men from over the sea. Our feelings for them are inspired by the loftiest and noblest emotions. They and we stand together as comrades in the greatest crisis that has ever confronted mankind. That the world may be saved for humanity, that civilization shall be preserved, our soldiers and sailors fight as brothers on land and sea.

Mapping the Missions

Today, there is a need to put the Japanese mission trail on the map before it is lost to time. Historical missions like the Wintersburg Mission have been demolished or are in jeopardy. The Wintersburg Mission—the oldest Japanese church in Orange County—is at risk of being lost forever due to the Huntington Beach City Council’s approval on November 4, 2013, of an application for demolition, as are all six historic buildings at the Historic Wintersburg property.

Part of the Wintersburg Village community gathering for the dedication of the second church building at Historic Wintersburg, the 1934 Depression-era Church. The occasion also marked the 30th anniversary of the Mission's founding. The diverse crowd represents the support the Mission effort received from the surrounding countryside. (Photograph courtesy of Wintersburg Presbyterian Church) All rights reserved. ©

*This article was originally published on the Historic Wintersburg blog on November 21, 2013

© 2013 Mary Adams Urashima