Last May 23, I completed 10 years as Administrative Secretary General at the Brazilian Society of Japanese Culture, known as Bunkyo. In December 2006, the full name of the institution was changed to Brazilian Society of Japanese Culture and Social Services, but that’s a topic for some other time.

May 23 is an important date for the city of São Paulo. On this day in 1932, four young students were murdered by federal government forces, an event that led Paulistas1 to join forces in the fight against the burgeoning Getúlio Vargas dictatorship.

I succeeded Senichi Adachi, who held that post at Bunkyo for 33 years, having been an employee for 46 years. Considering that in 2003 (the year he left) Bunkyo was completing 48 years of existence, Adachi basically accompanied the whole course of the institution.

Before Adachi, there was Takuji Fujii, the first Secretary, who assisted Bunkyo’s founding President Kiyoshi Yamamoto, starting out with the first successful post-war project undertaken by the Japanese-Brazilian community, the erection of the Japanese Pavilion at Ibirapuera Park in 1954. The realization of this project led to the birth of Bunkyo.

Ibirapuera Park was planned to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the city of São Paulo; at its entrance, an obelisk was installed, and in its interior is found the mausoleum of the four students and all other Paulistas who fell during São Paulo’s war against the federal government in 1932. The obelisk faces Avenida 23 de Maio, one of São Paulo’s main arteries, a North-South connecting route.

I became the third Secretary of what is considered the centralizing entity of the Japanese-Brazilian community five years before the expected celebration of the Centenary of Japanese Immigration—in other words, the 100th anniversary of the arrival of the first Japanese immigrants at the port of Santos [33 miles from the city of São Paulo] on June 18, 1908.

Adachi and I worked together for about 40 days. From May 23 to June 30, on a daily basis, he passed on to me the essentials of his job and of the activities at the institution. I helped him to organize several events, but beginning in July his visits became more sporadic as he had to take care of his failing health.

He convinced the directorship to allow me to accompany Kokei Uehara, the Bunkyo President who had begun his tenure the previous April, on his first trip to Japan. On the night that the directorship approved my trip to Japan, Adachi fell into a coma, passing away several days later, on August 15.

August 15 is an important date for both Japan and humankind. In 1945, after A-bombs were cowardly dropped on the civil populations of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allied forces, thus bringing World War II to a close. Nine years later, on August 15, 1954, Japanese carpenters—some of them having arrived from Japan, the others being Brazilian residents—completed work on the Japanese Pavilion at Ibirapuera Park, which, not long before had been a seedy marshland area, and that would be turned into the central park of the largest metropolis in South America and in the Southern Hemisphere.

Those were great times for projects, construction work, and, chiefly, for dreams to create a harmonious and peaceful society, with respect for diversity.

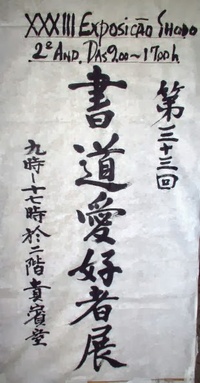

At that time, after a hiatus of 10 years or so, Brazil was once again receiving Japanese immigrants. Among them is Takashi Wakamatsu, who arrives in 1954 aboard the “Brasil Maru,” having earned a degree in Portuguese from Tokyo’s University of Foreign Languages. He starts working as a translator at Jornal Paulista—published in Japanese—and, later on, enrolls in Economics at Mackenzie University, beginning work at the Japanese Consulate in São Paulo. He becomes a businessman with a brokerage firm, but among the younger crowd he is better known as a teacher of “shodo,” the art of traditional Japanese calligraphy, with paintbrush and India ink. Wakamatsu is responsible for the annual “shodo” art exhibit that takes place at Bunkyo’s Noble Hall, which is in its 34th edition this year.

One of the habits of Bunkyo’s old regulars was to chat in the “Secretary’s office.” It wasn’t even a real office, but a mere cubicle. Still, many relevant issues regarding the fate of the Japanese-Brazilian community were certainly discussed there. Since 2003, I’ve witnessed a number of very important goings-on. I can only imagine what Adachi and Fujii witnessed during those golden years, when the Japanese-Brazilian community was known simply as a “colony.”

In 2009, the little cubicle was removed and few people have showed up since then, though Wakamatsu spent some time with me the other day.

The truth is that, if there are people, with or without the little cubicle, ideas will be developed.

It is said that the movement of the Japanese-Brazilian community is dying down, especially as far as youth is concerned, for they lack interest in the preservation and dissemination of Japanese culture. Even so, through the community’s institutions one can see that nowadays many more events are taking place, with much bigger attendance—more so than during the peak years of the “colony.” These events feature the participation of more than just the Nikkei, while also counting on the support of businesses and government institutions.

Wouldn’t that be the exact realization of those dreams of 50 years ago?

Quickly, Wakamatsu came up with a reply: “Goo-san, yes, there are many more events, we’re all very busy. But imagine a candle, before it burns out, the flame flares up and then ...”

And life goes on.

Note:

1. Paulistas are natives of the city of São Paulo.

© 2013 Eduardo Goo Nakashima