It has been said by many that writing letters is a lost art form. People under the age of 35 or so may have never experienced the sentimental emotions of discovering that dusty old shoebox full of beautifully crafted letters that convey love, joy, sorrow, and introspection. The grief-stricken letter with tear-stained handwriting or the scented love letter expressing longing and passion cannot compare to a laboriously long email thread or be reduced to a 140-character tweet with an embedded emoticon.

I recently had a remarkable shoebox moment when I came across several wartime letters written by my aunt, Itsuyo Kaku Hori (or “Aunt Its” as we called her), while she was incarcerated in the Santa Anita Assembly Center and the concentration camp in Heart Mountain, Wyoming. The letters were unknown to me until UC Davis professor Cecilia Tsu visited JAMsj and, by chance, informed me that she had discovered the letters when she was performing research at the History San Jose archives. The letters were sent to Elizabeth Wade, who was the friendly and caring landlord of the San Jose property where my aunt and her family farmed before the war.

Those personal letters, as well as other wartime correspondence and documentation that I have collected, challenge us with the concept of what it really means to be an American. The letters also dramatically reveal a tumultuous period that propelled my young aunt into an incredible emotional journey and a great personal transformation.

The first letters that she wrote from Santa Anita captured my 19-year-old aunt’s youthful innocence, optimism, trust, and naiveté. She mentioned the arduous, seventeen-hour train ride from San Jose to Santa Anita, how she missed the ranch in San Jose, and the long lines of people waiting for their camp meals. But she also remarked that Santa Anita is “a nice place” and that ”the race track is beautifully built with a large grandstand.”

Persons of Japanese ancestry arrive at the Santa Anita Assembly Center. Courtesy of National Archives and Records Administration (NARA).

“There are millions of people from all directions,” Aunt Its wrote. She was awestruck. “For you know that this is our first experience to see such a big place with so many people, that it will be a great, big adventure to us. We don’t know how long the government is going to keep us here, but we are well satisfied. It’s amazing to see what the government can do for so many people at this and the other camps.”

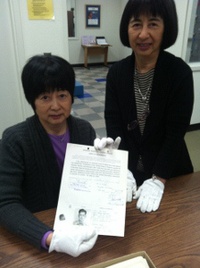

My cousins, Kathy Chang and Noreen Kudo, view the wartime letters that were written by their mother (my Aunt Its) and other documents at History San Jose.

Aunt Its wrote to Elizabeth Wade every two months. And she continued to write the “newsy” letters, as she referred to them, after the family was transferred to the Heart Mountain concentration camp. She wrote cheerfully, “This is our first experience in snow and it looks so pretty and white. The children seem to enjoy themselves by playing snow fights and making a snowman.” Coincidentally, she mentioned that she saw “the young Mr. Sakauye every time I go to the post office.” (I wasn’t aware that she knew JAMsj founder, Eiichi Sakauye).

These later letters from Heart Mountain also conveyed the first depictions of hardship. She remarked that the cold weather “affects the old folks very much, especially our Mom. She says that she feels as though her ear has been taken off. We all wish this war would be over pretty soon, but I guess it’s for the time to decide it. Let us all wish for the best of things now.”

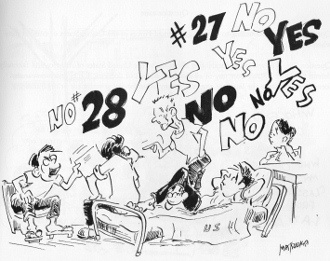

Strangely, the continuous stream of letters comes to an abrupt halt in March 1943. I’m not sure why, but this is the same month the family requested repatriation to Japan (the request was rescinded a few months later). In addition, it was around the time that the highly controversial “loyalty questionnaire” was issued at Heart Mountain.

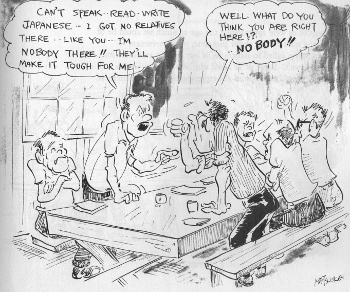

My father recounted to me many years ago when he was still lucid that the camp became a highly volatile place during that period. He recalled that there were people who applied great pressure on him to take a stand one way or another on the questionnaire. He remembered that whenever he had a meal in the mess hall, there was always somebody on the other side of the table emphatically demanding that he answer the questionnaire according to their strongly held point of view.

Jack Matsuoka’s memories of the heated arguments that raged within the camp over the “loyalty questionnaire” are depicted in his book, "Poston, Camp II, Block 211." My family remembered similar tense moments. Matsuoka’s artwork is on display at the Japanese American Museum of San Jose (JAMsj).

Perhaps because my Issei grandfather wanted the family to repatriate to Japan, his children who were old enough to sign the questionnaire did not answer the controversial questions #27 and #28 in the affirmative. Although government records show that my father argued with his father because he wanted to stay in America and that he subsequently registered for Selective Service, he did not answer the questions, which was considered the same as giving a negative response. He was thus labeled as a disloyal “No-No Boy.”

Most people who answered “no-no” to questions #27 and #28 were moved to the Tule Lake Segregation Center, a high security camp in California near the Oregon border. The results of the questionnaire eventually separated my aunt from the rest of her family. After getting married, my Aunt Its decided to stay in Heart Mountain while the rest of the family was sent to the Tule Lake.

Local artist, Jack Matsuoka, states, “Discussion and debate on the questionnaire issue grew heated and not infrequently led to quarrels and fights. ” This sketch is from Matsuoka’s book "Poston, Camp II, Block 211."

Transcripts of my aunt’s leave clearance hearings reveals a young woman who was undergoing a radical transformation in her thinking. Her husband failed to report to his draft induction, demanding that he would serve in the armed forces only if his rights were fully restored. My uncle is subsequently arrested and sent away to a Department of Justice camp and then later to Leavenworth Federal Penitentiary. My aunt is left alone in Heat Mountain, separated from her husband and her family. Her earlier feelings of optimism, trust, and hope are now replaced by confusion and cynicism.

Anderson (Assistant Project Director): How has all this made you feel toward the United States?

Hori (my aunt): Before evacuation, it was swell, it was all right, just like other people. I felt good, but since being put in camp, it is something different.

Anderson: As far as the future is concerned, do you feel that you could live your life here and be satisfied that you are an American?

Hori: It is hard to tell right now.

Anderson: You may feel that as a citizen you haven’t been treated right, but there is no question about your being a citizen. You are. Do I understand that the thing that you object to, you disagree with, is the fact you have been evacuated and have been required to live in a relocation center?

Hori: Yes. As citizens we should be treated like other Americans.

Anderson: You still think that under these conditions, you could be a sincerely loyal American, or do you feel that would make you feel a little bitter toward this country?

Hori: (No reply)

Assistant Project Director Anderson continued to press the argument that it is a citizen’s responsibility to report for military service even though he or she is forced into a “relocation center” and that the two issues are separate and should not be confused.

Anderson: Why do you think that you and your husband are any different than myself in regard to such an obligation? You think that I should go, but you feel you and your husband are justified in not going (to join the army).

Hori: They should give us some of the rights back to us, and then it is all right for us to go.

Anderson: What rights?

Hori: Rights of the citizen. Free to go out like other Americans before evacuation. They shouldn’t force us into relocation centers.

My father (far left, first row) and my uncles, seen here at Heart Mountain, were labeled as disloyal to the United States. After the war, when their rights were restored, one of my uncles served in the Korean War and made his career in the military. My father worked for the U.S Army in South Korea for nearly two years. To this day, some “No-No Boys” feel that they have been ostracized within the Japanese American community for the position that they took during the war.

Several members of the Leave Clearance Review Committee debated whether my aunt was truly a loyal American. One member wrote his review with underlined annotations for emphasis, “There are no indications of disloyalty, but rather a misconception of evacuation and Selective Service which has not been cleared up. If her husband and she are willing to suffer because of what they think American rights are, both would fight if they were given an understanding of the total picture.”

What they think? When I read this handwritten notation, I am amazed that people cannot see within themselves their own misconception about what American rights are.

My aunt stayed in Heart Mountain, separated from her husband and her family in Tule Lake. When she found out her father was dying, she had to obtain permission to visit him. Aunt Its told me once about the multiday train ride from Heart Mountain to Tule Lake. “The train was full of soldiers and nobody would give me a seat. Finally, one Japanese American soldier gave me a seat.” When she arrived at Tule Lake, the camp authorities recorded her fingerprints and took several mug shots. “We were discriminated against. We were Japs,” Aunt Its said.

There was another handwritten letter from my aunt in the government’s archives that stirs sadness within me. In her letter, my aunt emotionally pleaded with a government official to let her stay at the Tule Lake camp so that she could take care of her ailing father.

“When I met him, I was so shocked to see him completely changed from the time we separated last,” my aunt wrote in her letter to the project director. “That really was terrible for me to bear. I feel so sorry for my mother, watching her care for my father and children also. It makes me feel that I want to stay here forever and help, but I’m afraid that is impossible. I do not know when I will meet them (the family) again, and probably by then, he’ll pass away.”

My aunt was eventually given permission to stay at Tule Lake. She took care of her father until he died several weeks after the war ended.

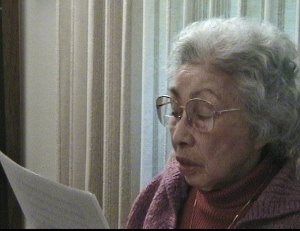

I was lucky to interview my Aunt Its before she passed away in 2007. Her controversial stories cover a topic that has been very difficult and painful for the Japanese American community. But, the stories also strike at the heart of the definitions of American identity, loyalty, equality, and justice. They have inspired me to ensure that her story, as well as the stories from others, are kept alive at JAMsj.

In my eulogy to her, I said that my aunt took me on a wonderful journey, resulting in my coming out as a different person on the other side. Discovering these previously unknown letters let me travel on that remarkable journey with her one more time. I hope that one day you will also find the “lost words” of a loved one so that you can embark on a similar journey.

My aunt was amazed that I was able to find her 1945 letter to the camp project director. I filmed her reading the letter in my interview with her in 2006.

* This article was originally published on the JAMsj Blog on December 16, 2012. The Japanese American Museum of San Jose’s (JAMsj) mission is to collect, preserve, and share Japanese American art, history, and culture with an emphasis on the Greater Bay Area.

© 2012 Will Kaku