In America, there is a great amount of interest about the origins of the fortune cookie. According to a study by Fitzerman-Blue, the fortune cookie—now served all across the country—is said to have gotten its start from chop suey restaurants after World War II.

Chop suey is an Americanized Chinese dish, consisting of pan fried meat (often chicken or pork) and vegetables, and bound in a starch-thickened sauce. In 1945, American soldiers returning to San Francisco’s naval base had first tried fortune cookies as a complimentary service at Chinese chop suey restaurants in San Francisco. The servicemen loved the cookies so much that, upon returning to their respective hometowns, they demanded their local restaurants for the same cookies, leading to the eventual spread of this complementary cookie service across California.

This story is often told to suggest that the Chinese had invented the fortune cookie, influenced by the free cookies served at these Chinese chop suey restaurants in 1945. However, this story may have room for reconsideration. That is because prior to the war, there is historical evidence of Japanese-made fortune cookies, distributed to Japanese owned chop suey restaurants in California.

In my investigation, I have found that the fortune cookie’s origins lie with the tsujiura senbei (fortune cracker), stemming back to the latter Edo period (1603-1868). It is believed that Makoto Hagiwara was responsible for bringing the manufacturing of this confectionary from Japan to San Francisco during the Meiji period (1868-1912); but for the purposes of this essay, I’d like to focus on the restaurants and the cultural background of fortune cookies.

There is a high likelihood that Japanese-owned chop suey restaurants were already serving free crackers as a dessert prior to the war. A senbei shop in Los Angeles called “Umeya” (est. 1924) is a mass producer of these cookies (tsujiura senbei) today, and even before the war, they were hand-making 2000 tsujiura senbei per day, distributing them to restaurants, small shops, and fruit stands, from Santa Maria to San Diego. Among the most popular distribution points were the 120~150 Nikkei chop suey restaurants spread across central and southern California.

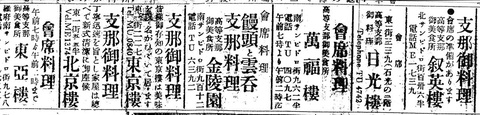

Chinese immigrants first began opening chop suey restaurants around 1896. Its presence spread from New York to San Francisco, and eventually the Japanese immigrants also began to manage similar-styled Chinese food restaurants. According to the collection of success stories in the “Directory of Japanese in Southern California” (1929), the first Nikkei chop suey restaurant was Dragon Chop Suey in 1917. In the same year, the same ownership group opened Chouchou Chop Suey, and the joint owners were hailed as Chop Suey Kings. High-end establishments began to classify their Chinese cuisine as akin to the Japanese style “Kaiseki Ryori” (banquet cuisine), intending to give it a sense of luxurious gourmet food.

Photo 1: Advertisements of chop suey restaurants promoting their banquet cuisine (“Rafu Shimpo”, Ad section, 9/12/1929).

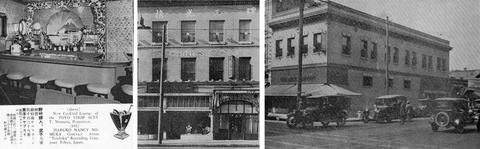

In addition to this, they imported a banquet-style setting affiliated with Japanese culture—complete with a performance stage and geisha for entertainment—which was a key component to the atmosphere of high-end restaurants in Japan. During the economic boom, there was Nikko Rou, a “high-class Chinese restaurant” touting their capability to entertain over 400 guests at once; and even places like the Eastern Chop Suey Lounge, which combined a restaurant with a western-style cocktail lounge (Photo 2: left). Ichifuji-tei, Kawafuku, and Sanko-Rou were among the members of the Rafu Restaurant Association, which suggests that these restaurants called upon geisha for entertainment back then (Photo 2: center and right). Ichifuji-tei and Kawafuku served both Japanese and Chinese cuisine, and it can be said that these larger Nikkei chop suey restaurants not only served to satisfy empty stomachs, but also to provide a space for socialization and amusement in a modern, attractive, and multicultural setting.

Photos 2 (From left): Eastern Chop Suey Cocktail Lounge (“Encyclopedia of Celebrations and Commemorations,” 1940); Outside of Sanko-rou (“Directory of Japanese in Southern California,” 1992); Ichifuji-tei (“Directory of Japanese in Southern California,” 1992)

It was during this era in which Umeya was distributing their cookies to the chop suey restaurants. So why was it that these fortune cookies were being consumed there?

In Japan, the tsujiura senbei was originally a confectionary often served at tea houses, small restaurants, and cafes as a complimentary side dish or dessert to pair with tea or sake. The tsujiura confectionary, which contained a fortune-telling slip of paper within itself, was often used as a prop to stir up the crowd at banquet parties. They were fancied as props in settings such as parties featuring geisha and barmaids, as well as a tool for breaking the ice when striking up a conversation with somebody new.

During the height of the Nikkei chop suey restaurant boom, the group that most prominently enjoyed the after-work parties at these extravagant restaurants were the successful men of the Issei generation. Perhaps it was inevitable that the newly immigrated Japanese would introduce a form of banquet party entertainment, representative of their homeland’s culture. I believe the historical demand for the cookies from these chop suey restaurants is an indication that there was a tradition of serving complimentary tsujiura senbei in the past. If not, it would mean that people were gathering in large numbers at restaurants and eateries, and that these grown adults were frequently placing orders for fortune-telling confectionaries—and I find that hard to believe. Therefore, the more likely explanation is that fortune cookies were served to compliment tea and sake at Nikkei chop suey restaurants in the pre-war America, just as it has been done at traditional and small restaurants in Japan.

© 2012 Yasuko Nakamachi