Read Part 8 >>

Walking a Fine Line

In Born Free and Equal, Adams struggled to walk a fine line between advocating for the imprisoned Japanese while not leaving himself vulnerable to charges of disloyalty. The Nisei, too, walked that line, balancing hurt and anger with a desire for approval from the country where most of them had been born. Born Free and Equal opens with a quote from the 14th Amendment of the Constitution guaranteeing all citizens of the United States the right to life, liberty, property and equal protection under the law. This is followed immediately by a quotation from one of Abraham Lincoln’s letters:

…As a nation we began by declaring that “all men are created equal.” We now practically read it “all men are created equal except negroes.” When the know-nothings get control it will read “all men are created equal, except negroes and foreigners and Catholics.” When it comes to this, I shall prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty…where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.

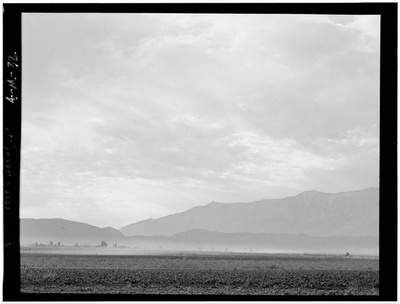

This powerful selection, which equates the treatment of Japanese inmates to that of African slaves, gives way to Adams’s own, more muted words, conveying his focus on nature and his disavowal of any attempt at “sociological analysis.” “While the people and their activities are my chief concern, there is much emphasis on the land throughout this book,” Adams wrote. “I believe that the acrid splendor of the desert, ringed with towering mountains, has strengthened the spirit of the people of Manzanar…The huge vistas and the stern realities of sun and wind and space symbolize the immensity and opportunity of America – perhaps a vital reassurance following the experiences of enforced exodus.” Adams, the peerless interpreter of Nature, appears to prescribe it as the antidote to all that ails the imprisoned Japanese.

Memorial Day services at Manzanar. In the background, the "towering mountains" that Adams asserted would "strengthen the spirit" of prisoners. Photograph by Francis Stewart. (Source: WRA photographs, No. D-535.)

This widely criticized statement, implying that political and moral crime at the heart of Manzanar could be overcome or absolved by the superior forces of nature, seems a Pollyanna-ish or willfully naïve view of Manzanar. Yet my uncle described the first dawn he and my father witnessed at Manzanar in language as exalted and awestruck as that of Adams:

The cold wind of the night before had abated and the air was free of the swirling dust that we had first encountered. We had arrived at Manzanar at dusk the previous day, April 28, 1942, and the environs of the camp, obscured by sand and dust, could not be readily observed in the failing light. Not only was visibility limited but breathing had been difficult. Our attention then was preoccupied by our barrack assignments, claiming our bedding of a mattress cover to stuff with straw, setting up our folding canvas army cots and getting a bite to eat. All of this happened well after dark.

Instead of symbolizing the "immensity and opportunity of America," as Adams hoped Manzanar's vistas would, dust storms such as this one tested the endurance of prisoners. Photograph by Ansel Adams (Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA)

Memories of our first morning in Manzanar are still fresh in my mind. I awoke well before dawn and coaxed my brother David out of his cot to watch what turned out to be a spectacular sunrise. The wind had died during the night and the stars, due to the absence of city lights and smog, appeared more beautiful and numerous than I had ever seen them, so close that we could almost touch them. The air was clear and fresh without a trace of the choking dust of the night before. It was still dark as we made our way to the edge of the clearing above Block 18. We shivered from the unaccustomed cold of predawn Manzanar and stoically awaited the dawn to reveal to us our environment, still only massive dark shadows looming to our west, well out the sweep of the searchlights atop the watchtowers.

Gradually, the sky to the east began to lighten and we began to discern the relatively low-lying hills to the south, which we later learned were the Alabama Hills. Colors began to creep in, filling the outlines of the surrounding objects. To our west was the hulk of a towering snow-capped mountain range, the Sierra Nevada. To the east was the dark red-brown Inyo Mountain Range. Arid as the desert and not as awesome as the towering snow-covered Sierras to the west, it was still a formidable barrier to cross.

Memories of Manzanar, for many internees, are bleak and bitter. But to me the Owens Valley is still spectacularly beautiful. One only needs to spend a few minutes in this high country to fathom the meaning of naturalist John Muir’s description of the Sierra as “the range of light.”

Soon the tips of the crests of the Sierra caught the glint of the morning sun still hidden behind the Alabama Hills. I watched in amazement as the crests, where they were not covered with deep snow, turned from a deep purple, to dark brown, to pink, to a reddish gold before my eyes. The light reflected off the snow and the peaks had a “presence.” Every few seconds the shadows and shading metamorphosed magnificently. As the sun rose higher, the mountain range became bathed in sunlight from its peaks almost to its base. Finally, in a matter of minutes, the sun burst over the low-lying Alabama Hills as with a nuclear blast, drenching the entire valley in its warm golden rays.

The birds, yet unseen, had started their serenade, timidly at first then increasingly loudly until their song could be heard from every quadrant of the sun-drenched valley. Still, there were no signs of life among the barracks. We made a quick trip to the latrine and slipped back quietly into our unaccustomed cots for a few winks. It was an unforgettable experience. The impressions of that first morning, while not of a Garden of Eden, awoke me to the primitive and raw beauty of Manzanar and the Owens Valley, a place that others would call hell on earth.

Wonderstruck by the beauty of his new surroundings, Uncle George’s description demonstrates a typically Japanese reverence for splendid vistas that has roots in the nature worship of Shintoism. The kinship between this view and Adams’s love of the natural world is striking, and another source of the affinity of the Nisei for Adams. Mountains and sky were spiritual in nature, a source of strength and hope.

Adams’s parents were not churchgoing, but he was influenced by his father’s regard for Ralph Waldo Emerson and the other Transcendentalists. Part of their appeal to both Adamses was their rejection of doctrinaire religion for a more intuitive and individual communion with the divine. As Ann Hammond wrote of Adams, “Throughout his work he represented the continuity and interconnectedness of natural elements of trees, rocks, streams, and clouds to form a theosophical universe in which the forces of evolution also advance human consciousness.”

Adams called the beautiful inmate-designed and cultivated Merritt Park (named after camp director Ralph Merritt) a "pleasure park." Photograph by Ansel Adams. (Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington, D.C. 20540 USA.)

© 2011 Nancy Matsumoto