Read “Part 5: Monsters” >>

The Constant King 1964

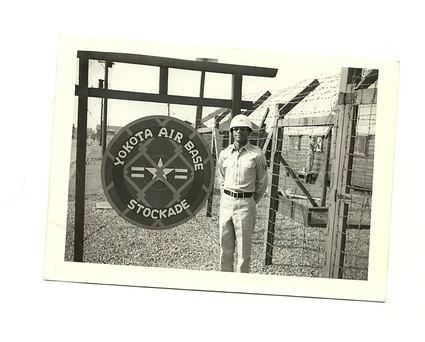

Mama and Dad and myself are at the dinner table. It was really the first full year ever, that Dad sat at the dinner table with Mama and I for a meal or two. In the past, he had been out of the country where Mama and me lived. When I was born it wasn’t good that he was with us, according to the military. So he was in America and Korea. In America, after only a couple of weeks, he was to go to the battlefields of Vietnam. In Hawaii, when he was living with us, he was rarely home.

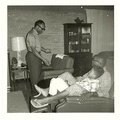

In 1964, two years after our family had moved from Japan to America, we lived in a nice brick house which looked like all the others on the east side of Kirtland Air Force Base in Albuquerque. I was 11 years old. Dad was out with his friends every night or building a piece of furniture at a hobby-shop. The only time I would see him was for about two hours around dinnertime everyday.

One evening at about 6:30pm on a Friday, Mama had just put the rice cooker with hot puffy steamed rice on the table. It was the first or second time I remember, that we had sat together for a meal. After Mama set the rice cooker on the table, she brought the plate loaded with well-done pork chops that Mama diligently learned how to cook because Dad loved it and I learned to love it immediately too. Then a large bowl of boiled spinach with bonito flakes and sweet shōyu, followed by a plate of buns, then a plate of green beans were placed on the table. Some brown gravy brought in a Japanese serving bowl is brought in a few seconds later. Oishi sou! On the table there is the glass bottle of Coca-Cola and the genmai-cha that all of us loved. Mama did most of the cooking, although sometimes Dad would cook so that Mama would have a rest and felt that he could do things for her that gave her, perhaps, a bit of joy. That’s what Mama loved about Dad. Dad tried as hard as he could to think of her.

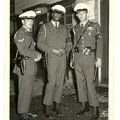

As usual, Dad was silent during dinner. He wasn’t icy or cold, but quiet. Sometimes he would tell a joke or ask how our day was. I knew that, like me, Dad enjoyed eating. It was also, for him, a time for the family to be with each other without distraction. It was also something engrained into him since childhood in Nashville, Tennessee and in Detroit, Michigan, where his mother would call him and one of his brothers together for a meal, which was rare while his mother worked two jobs. At first in poverty, with a single mother, in an African-American family trying to rise up and out of their circumstances in the 1940s, meals were an important time to be grateful for abundance and to enjoy the sensuality of eating.

Following these histories, our meal times were usually silent if we didn’t have Dad’s friends over and our meal was just the three of us. The television would be turned off, then turned back on after we were done eating. Mama was busy running around making everything perfect. In typical old Japanese fashion, she would eat last. Dad would be reading the evening newspaper at the dinner table, then when everything is set and Mama sits at the table, he put the newspaper away and we begin eating.

As a teenager, I wasn’t used to his presence after most of the years living with just Mama. Mama didn’t have rules at a dinner table. But that probably wasn’t fair to say. It was more like I ate Japanese. My way of eating was something I learned organically in Japan, with others. But it seemed that my Dad, like most of my American friends’ families at dinner, had a lot of rules: don’t put your elbows on the table; don’t burp; don’t fart; don’t fidget; pass the food before you eat; sit up straight; don’t use your fingers to push your food; on and on and on and on. Eating was almost as much of a chore as much as joy, when eating with Dad.

But he loved food. That was something Dad and I had in common. My mother did not like food and always ate sparingly. Later, I knew that it had much to do with her experience in war-time and postwar Japan, where food was scarce and she would feel guilty for being in an upper caste family where food was slightly more abundant while many of her friends were constantly on the brink of starvation for years. Mama was always attracted to soup kitchens in Albuquerque that served the homeless. I figured out one day that it was a wartime image that she chose to remember and keep as a way of feeling thankful for life in the face of all her difficulties. Eating for Mama and I had deep roots. For me, eating was an emotional comfort and was a way of preserving memory.

From the serving bowls Mama would put our individual servings onto our plates or into our bowls. I picked up the bowl of miso soup and began drinking it as usual. Then all of a sudden: a SLAP on my hand!!! The bowl in my hand is knocked out of my hand and is flung over and spilled onto the dinner table. The miso in my bowl is all over the front of my part of the table. “WHO TAUGHT YOU TO EAT LIKE THAT?” he intensely says to me (my father never yelled, he was against yelling). Blaming Mama indirectly, putting us both in our place according to his view of proper, Western/American way of eating that he had been taught in his self-development from little black boy to American man, American soldier, the teacher of the high morality.

I was silent. In reality, it was mostly because I didn’t even know what the hell Dad was talking about. “You don’t pick up the bowl to eat like some kind of savage.” I thought: What? Then I understood after a couple of moments, that I was supposed to use a spoon to eat ALL soups as he held a spoon in front of my face. In Japan, I had learned that you drink soup by picking up the bowl up and drink it (unless it is a large bowl).

Then, Dad turns to Mama and says “Did YOU teach him how to eat like that?” with an angry tone. Mama is silent and looks ashamed, glancing down and looking at the floor. I turn to look at Mama for either support or an answer to Dad. She glances at me with a disapproving look. I stay silent. Dad then continued: “Pick up the bowl and clean this mess up!” I comply. I felt alone. I knew that Mama did. I also felt betrayed (selfishly speaking as a 11-year-old—I expected her to explain to Dad that this is how we usually drank miso and other soup). I cleaned up the soup mess. Mama helped. There is a cold silence at the dinner table.

Now I think my mother was in a hard position. Cultural differences. With the Man of the house. Occupier, Occupied. The victorious and the defeated. The modern and democratic versus the child-country, the uncivilized, the on-the-way-to-possibly-becoming-democratic object. The man-king, the woman-made-docile. The arrangement of nation and gender and race has been stipulated. Certainly, as a child, we were just supposed to obey, becoming a mirror or its opposite.

I remember in that moment I knew I never wanted to be like him. I respected and admired him in many ways. But this kind of way of being with us wasn’t something that Mama and I should bear. Why should we eat his way? I kept it to myself. I learned that he wasn’t around all that much so I would just listen to him and do what he told me while he was around. But most of the time, he wasn’t. So I didn’t make a fuss of it. But at the same time, I didn’t want to be like Mama either.

And what could I say anyway? And as the years went on, Mama learned to slowly become more vocal in her disapprovals and different opinions with Dad. At that dinner, she had learned to practice not shaming her husband and to teach her son to be compliant to the father. And now, I eat at American dinner tables without my elbows on the table and drinking soup with a spoon—except for whenever I eat Asian soups in small to medium bowls. I didn’t need the soup spilled on my lap or the humiliation of Mama who had raised me, by the person who was never home. I had separated.

This is an anthropology of memory, a journal and memoir, a work of creative non-fiction. It combines memories from recall, conversations with parents and other relations, friends, journal entries, dream journals and critical analysis.

To learn more about this memoir, read the series description.

© 2011 Fredrick Douglas Cloyd