>> Read part 6

Informal Education: Making Meaning of Incarceration

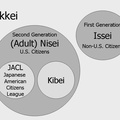

Even before war broke out between the United States and Japan, the FBI and army and navy intelligence had been suspicious of the Nikkei, particularly those living on the U.S. west coast and in Hawai‘i. Since 1939, the agencies had been keeping lists primarily of suspected Issei (Japanese immigrants) but also of some Nisei—their children, who were American citizens. Soon after the Pearl Harbor attack, the FBI arrested those they labeled as dangerous.1

On 19 February 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066. With a stroke of his pen, and without regard for the U.S. Constitution, he set in motion the process of forced removal and incarceration of a people who had not been charged with any crime. The Order ultimately gave the Western Defense Commander Lt. General John L. DeWitt the power to exclude from designated “military areas” “any or all persons.” Although “Japanese” or “Japanese Americans” were not explicitly identified in the Order, it was clear that they were the targets. DeWitt followed through by declaring as military zones the western half of California (later the entire state), western Oregon and Washington, and southern Arizona.2

Nikkei living within DeWitt’s exclusion zone were taken to temporary “Assembly Centers” managed by the Wartime Civilian Control Administration (WCCA), an agency of the U.S. Army’s Western Defense Command (WDC). (Several thousands had left legally before DeWitt’s March 27 deadline.) “Without charges, without proof, without hearings, with only a few days’ to a few weeks’ notice, and forced to leave behind their furniture, appliances, farm equipment, automobiles, and other possessions, they were herded into makeshift barracks at racetracks and fairgrounds in and near the major West Coast cities.”3

With the Nikkei in the Assembly Centers by the summer of 1942, a newly created civilian agency, the War Relocation Authority (WRA), assumed responsibility for the confined people. Milton Eisenhower, the first director of the WRA, made an unsuccessful attempt to convince governors of the mountain west to allow the Nikkei to resettle in their states. Unable to overcome the governors’ resistance, the WRA decided to designate ten sites for the confinement of the Nikkei. Called “Relocation Centers,” the sites were situated in desolate and forbidding areas of the country.

While the federal government stated that the Relocation Centers were created for security reasons, scholars today agree that these camps for Japanese Americans (identified as “concentration camps” by government officials before the term was replaced by the euphemistic title, Relocation Centers) came about as a result of “public hysteria, virulent racism, and economic and political opportunism.”4

Kurihara was directed to go to Manzanar, which was first designated as an Assembly Center and later reclassified as a Relocation Center. Located in California’s desert region, the camp was subjected to extreme temperatures, ferocious winds, and heavy dust storms. Five miles to the north was its nearest town, Independence.5

By the end of May most of the men, women, and children who were to live in Manzanar had arrived. They were housed in wooden barracks within a square mile compound that was surrounded by barbed wire and guard towers. Each barrack was divided into rooms, each 20 by 25 feet or less, with one room per family. The barracks were built of plywood covered with black tar-paper. Cracks between the planks and lack of insulation would allow the desert heat, the swirling dust storms, and the freezing winter weather to penetrate into the rooms.6

Sixteen barracks formed a block, which included a mess hall, laundry facilities, and latrines. A total of 36 blocks would hold many as 10,000 people, the peak number living in Manzanar during its three-year existence. Also enclosed were a rudimentary hospital, a store, a church, an orphanage, administrative housing, support facilities, and other buildings. Just beyond the barbed wire were a reservoir, a sewage treatment plant, agricultural fields, and a cemetery.7

On 1 June 1942, the WCCA turned over its administrative duties to the WRA. With that transfer, Manzanar, which had been an Assembly Center, was now a Relocation Center (figure 4).8

Figure 4. Manzanar from guard tower, showing buildings, roads, and the Sierra Nevada mountains, 1943. Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Ansel Adams, photographer, LC-DIG-ppprs-00200.

Notes:

1. Yuji Ichioka, Before Internment: Essays in Prewar Japanese American History, eds. Gordon H. Chang and Eiichiro Azuma, (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2006), 197; Harlan D. Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry during World War II: A Historical Study of the Manzanar War Relocation Center (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1996), 12; Eric L. Muller, American Inquisition: The Hunt for Japanese American disloyalty in World War II (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 15-16; Roger Daniels, Concentration Camps: North America, Japanese in the United States and Canada during World War II (Malabar, FL: Krieger Publishing Co., 1993), 39, 71-72.

2. “Executive Order No. 9066, 19 February 1942, Authorizing the Secretary of War to Prescribe Military Areas,” Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum. http://www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu/od9066t.html (accessed 7 October 2008). For analyses of the discussions and activities that led up to forced removal of West Coast Nikkei, see Daniels, Concentration Camps, 42-73; Roger Daniels, The Decision to Relocate the Japanese Americans (Philadelphia: Lippincott, 1975); Peter Irons, Justice at War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 25-47; Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1997), 72-92, 111-12; Morton Grodzins, Americans Betrayed: Politics and the Japanese Evacuation (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974 [1949]; and Jacobs tenBroek, Edward N. Barnhart, and Floyd Matson, Prejudice, War, and the Constitution (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1954).

3. Muller, American Inquisition, 21. See also Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, Personal Justice Denied, 100-12; and Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation of Persons of Japanese Ancestry, 63-64.

4. Arthur A. Hansen and David A. Hacker, “The Manzanar Riot: An Ethnic Perspective,” Amerasia Journal 2 (Fall 1974): 120.

5. Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation, xxv.

6. Paul Howard Takemoto, Nisei Memories: My Parents Talk about the War Years (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2006), 126.

7. Unrau, The Evacuation and Relocation, xxvi, 377. For maps of Manzanar, see Jeffrey F. Burton, Mary M. Farrell, Florence B. Lord, and richard W. Lord, Confinement and Ethnicity: An Overview of World War II Japanese American Relocation Sites (Washington, DC: U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, 1999), 164-65.

8. The WCCA had called this site the Owens Valley Reception Center, which served as an Assembly Center from 21 March through 31 May 1942. On 1 June 1942, when it was transferred to the WRA, it was renamed the Manzanar War Relocation Center.

* This essay was the History of Education Society Presidential Address delivered at the annual meeting in Philadelphia, October 2009 and published in History of Education Quarterly, Vol. 50, No.1 (January 2010).

** The definitive version is available at www.blackwell-synergy.com.

© 2010 The History of Education Society