This is an anthropology of memory, a journal and memoir, a work of creative non-fiction. It combines memories from recall, conversations with parents and other relations, friends, journal entries, dream journals and critical analysis.

To learn more about this memoir, read the series description.

The Dream

“To say that a life is precarious requires not only that a life be apprehended as a life, but also that precariousness be an aspect of what is apprehended in what is living.”

—Judith Butler, Frames of War: When is Life Grievable?

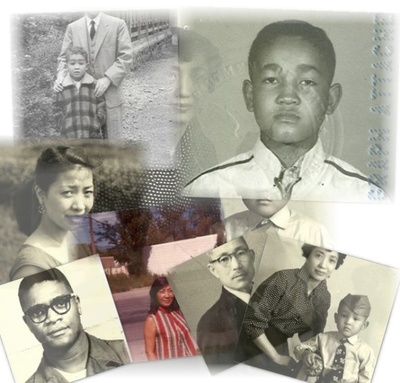

I was born in July of 1955, in a small town in Japan. My mother is Japanese, born in China in the ‘30s. My father is African-American born in the late ‘30s. I’ve been to the Netherlands, Turkey, Germany, the UK, all over Canada and Mexico, have lived in Colorado, upstate New York, Chicago, Hawaii, New Mexico, and Washington State. Now I am living in San Francisco.

It wasn’t until I was in my 30s when I began intensifying my interest in my family history. My history is not any more special than anyone else’s. However, it is more invisible and therefore prone to being dominated by larger discourses traveling around in people’s heads and actions. So as life experience accumulated and I continued to reflect and learn, I wanted some gaps of time and knowledge to be filled. I remember moments where I asked questions to my uncles or parents and they wouldn’t answer or say “I don’t remember.” “Wasureta.” There were times when they said they’ll tell me later. At other times, they refused and said “it isn’t important.”

In my single bed that held my almost 6-foot brown body in my SRO:

2:00 in the morning.

I twisted to turn onto my other side, trying to go to sleep. I turn again onto my other side. I feel the breeze through the room from my south window. The covers become a bit of a burden and I shrug them off of my shoulders so that the covers are now around my chest, exposing my shoulders to the night air moving through my room.

Suddenly I sat up, click on the bedside lamp on and grab a pen and open the drawer of my bedside table to grab the small note pad. I begin making a list.

Water.

水 – “Mizu,” Japanese word for water. The character came from Chinese writing.

子 – “ko” – child, baby, infant

Together: Mizuko

Ways of writing “mizuko”:

水子

みずこ

みず子

ミズコ

Mizuko

mizuko

水子 Mizuko is a common proper name for girls. women.

Mizuko is also a euphemism for: Dead Fetus, still-born, aborted or miscarried baby / babies

- dead baby / dead babies / dead infant / dead infants killed.

- child / children who died very young

- a child who “returns” to the waters, womb (dead to be reborn)

I become scared. Afraid of why I am writing this list. What a strange list? Why am I writing this?

Writing memory which entails the writing of forgetting—what does this say about how the world is, how imperfect it is? And how are we accountable to these stories? Stories of Japanese women like my mother, who married American servicemen in World War II are numerous, as are those of Korean, Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, and other women of the Asia-Pacific, who have done so.

There are numerous stories of Amerasians, mixed-race, and multiracial persons as well, although not always identified as those labels. In most of these cases, in mainstream writings, the words and stories written have focused on their lives as anomalies: tragic, obscure, or as wonderful representations of “the future of humans.” In all these cases: we Black-Japanese, are not here in those frames except as objects.

One reason for this, I feel, is that these identity-markers themselves, carry histories and memories within the categories. They defy actual lives with their uses and hold like prisoners, the diversities and social justice issues that indict certain realities that don’t want to show their faces, their truths to be confronted. And if the bodies, like mine, are relegated to “less important” or “minority,” then even more so are we negated. I write my family history not as a history, but from that space of breaking from prison.

I leave archive, not only of identity but how that identity is performed in relation to what is happening. In addition, what carries over and what are people doing about it?

I think of my childhood friends in the places my body carries: Ōme, Murayama, Tachikawa, Tachikawa Air Force Base, Yokota, Washington Heights, Shōwa, Fuchū, Nara, Shakudō, Ōsaka, Tōkyō, Halawa, Aiea, Honolulu, Albuquerque, Kirtland Air Force Base. I think of the times I remember in 1957 through 1962, 1962 through 1966. 1966 through 1968. 1968 through 1970. 1970 through. My own markers in years. My mother’s friends that often baby-sat me when I was a child, who suddenly disappeared. What happened? Why the silence of my mother’s shiranai (I don’t know)? Who was my father to us? As I barely knew him as a child and as an adult, his presence is noticeably more of a strong but ghostly figure in this dynamic. Then there are those who cannot speak and are perhaps strangers, who are related, whose stories weave through ours. I want to bring them here in however small ways. Otherwise, who else would know they exist as important in a larger story?

My words and body are like a finger pointing at memory1 and the circulation of dominance and resistance, assimilating memory and resisting assimilation.

This is almost an anti-memoir. Memory is thinking, not just a series of events that are a given in sadness, rage, or numbness.

It is collective memory and multi-positioned journaling. It is about inter-generations and different kinds of families that exist in the world, not necessarily blood related but politically-sociologically-anthropologically connected.

Or even, shall I say—connected by being involved with killing and being killed, spiritually and/or physically.

It reflects and moves in and out, back and forth. It is troubling. And not because I am more troubled than other subaltern identities. Troubled because of what words and political and cultural positions and categories do for me to have to need to speak to.

What I mean to say is that there is hope and there are people and there are ways to defuse unnecessary suffering.

One such way is to present the tracings, paths, disfiguring, the layers, the mantelpieces of authority and normalcy, the legacies that continue things, break things. Legacies that begin, add onto, take away, shift, between generations of people, within families, within nations.

* * * * * * *

The concept of a Black-Pacific—its forms and subversions, is a question I have that may speak to the present breakdowns and re-configurations, as well as the general amnesia that plagues our postcolonial life in the 2000s.2 I speak to the struggle for understanding, justice, diversity, and fullness, in a world that increasingly valorizes an emptiness through which the elite can fill our “selves” with what they fill us with, making the world smaller and therefore increasing the spaces where hegemony can play.3 When I do this, I feel the Black-Pacific becoming more than that. Particulars are from larger worlds, larger spaces and times.

I present culprits that can and need to change—the hybrid forms of internalized tactics of dominance that mask themselves as freedom. I point to more freedom as possible. I tell them through tears. For my ancestors, for the dead, for the forgotten.

Italics: My mother’s memory, my mother’s words, words of my ancestors, words of my subconscious, titles of some books and authors and songs, are often written in italics, along with any words and phrases I want emphasized as you read them, as a body—a collective ghost, a collective unconscious that speaks in unison as we read.

To remember.

Insisting and entering together.

Bodies we must listen to, feel, contend with.

Whisper:

We visit you. We are visitors. We visit because you cannot forget.

We are not just here without a purpose.

We do not visit you for your fear or amusement.

Who are you, as person and ancestor, to time, to other, to violence, to love, without us?

Notes:

1. This is a direct reference to Zen Buddhism’s oft-quoted dialogue of a Zen teacher, when asked what Zen practice is, what Nirvana is, what “Truth” is, what enlightenment is. The teacher responds: It is like the finger pointing at the moon. Whatever I say about it, it is not the moon itself.

2. The idea of the Black-Pacific has become a new language of reference, interpretation, and study since Paul Gilroy’s studies of the Black-Atlantic as a reference point to speak of the legacies of the Atlantic Slave trade and its terrains in the Black Atlantic diaspora and its cultural forms, which by its very nature, would include identity, continuities, ruptures, and cross-space legacies. See The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, Verso 1993; There Ain't No Black In the Union Jack: The Cultural Politics of Race and Nation, Hutchinson 1987; and After Empire: Multiculture or Postcolonial Melancholia, Routledge 2004.

3. Merriam-Webster dictionary defines hegemony as: 1) Preponderant influence or authority over others: domination; 2) the social, cultural, ideological, or economic influence exerted by a dominant group. However, I want to stress the more important notion of cultural imperialism as a tool for cultural hegemony, as defined by the great Italian thinker Antonio Gramsci. Cultural imperialism is done in the everyday, spreading through what our lives are, in various ways, maintaining the status quo of relationships between differences. The hierarchy of socio-cultural classes within any society, may practice cultural dominance as a way to have lower classes adopt (internalize) and therefore enact the status quo. This will include the structural forms of language-concepts and language use, to which thinkers such as Judith Butler, Homi Bhaba, Jacques Derrida and Michel Foucault speak to, among others.

© 2011 Fredrick Douglas Cloyd