Read Part 6 >>

THE DEBATE OVER CITY VIEW

On August 17, 1984, the Los Angeles Times ran a story on City View Hospital entitled “Financial III Health Plagues an Ethnic Hospital.” For many of the Nikkei who read this article, this was the first sign they had received that the hospital was in crisis. The news was unexpected and immediately raised questions in the minds of many. After all, the community had contributed generously to the hospital each year, how then could it have suddenly fallen into crisis? And what should be done to avert the crisis?

These issues lay dormant for half a year, until the editorial “Is there a Need for a Japanese Hospital?” raised them again, in the February 2, 1985 issue of the Rafu Shimpo newspaper. In the editorial, the medical staff reviewed the events leading up to the current financial difficulties. The physicians asserted that the hospital had first neglected to modernize its facilities and next failed to prepare itself for the advent of the DRG system. They withheld their acceptance of affiliating with a larger hospital, which the Board of Directors had proposed as one solution to the crisis. Instead, they appealed to the community for its opinions on the future of the hospital.

Responses poured into the Rafu Shimpo office. They were unanimously in favor of continuing the hospital. Soon the debate spread to the editorial page of the Kashu Mainichi, the other Japanese newspaper in Los Angeles.

By February 27, the debate had spawned the “Ad Hoc Committee to Maintain the Memorial Hospital of the Japanese Community,” which was concerned about the finances and management of City View Hospital. After half a year, the community still wanted to know how the hospital had fallen into debt, before the question of affiliation could be addressed.

The debate spread to the Tozai Times, the third Los Angeles area newspaper aimed at the Japanese-American community.

By April, City View administration had not responded to the questions of the Ad Hoc Committee, and was coming under fire from various other groups in the community. Instead, the hospital board announced its decision to affiliate with Good Samaritan Hospital, a 411-bed non-profit hospital across town.

Predictably, the staff doctors and the Ad Hoc Committee opposed the move, and threatened to picket Good Samaritan Hospital in protest. The doctors also asked permission to conduct an independent audit of the hospital’s finances.

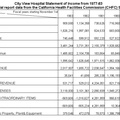

The staff doctors’ efforts were partially successful, for the threat of a picket caused Good Samaritan Hospital to suspend negotiations with City View on April 19, 1985. Their request for an independent audit was agreed to on April 5, but was delayed by a new development. Medicare audited City View and found that the hospital owed nearly a quarter of a million dollars to the program. Medicare planned to conduct a second audit, thus putting off the doctors’ request. However, on April 18, 1985 the hospital finally revealed its financial report for the fiscal year ending October 31, 1984.

The June 26, 1985 issue of the Rafu Shimpo carried the news that capped the debate. First of all, City View Hospital would discontinue its acute care services by August 1. Secondly, Coopers and Lybrand—one of the “Big Eight” accounting firms—announced the results of their independent audit of the hospital during its fiscal year ending October 31, 1984. The audit confirmed that the hospital had lost over $900,000 from its operations that year. The net income of the hospital and the nursing homes was $61,211. One of the partners at the accounting firm explained that “the nursing homes are in essence supporting the acute-care hospital…it should be the other way around.” He also felt that City View needed a forty percent occupancy rate if it was to break even.1

In July 1985 the medical staff, along with community leaders, formed a new non-profit organization—“Japanese Community Hospital, Inc.” Negotiating through this organization, the doctors announced ties to St. Vincent’s Hospital, obtaining use of a sixteen-bed wing to use as the “Japanese Community Hospital Pavilion.”

Finally, by the end of July, the medical staff transferred their last City View patients to St. Vincent’s Hospital. The debate had reached its conclusion, with the Board of Directors and the doctors both acting on their positions. City View Hospital had closed. The Japanese Community Hospital, Inc. was making its first steps to begin anew.

CONCLUSIONS ABOUT THE PROJECT

Before drawing conclusions about the project, I interject a quote about Sacramento’s Japanese hospitals to contrast the most recent with the oldest known Japanese hospitals:

By 1903, Japan town had a hospital called Japanese Hospital (probably a clinic) operated by Dr. M Matsuda located on 4th Street. This was no longer listed in the Directory after 1905. The next clinic, Takeoka Byoin, opened around 1907. This was followed by the Ofu Byoin (Sacramento Hospital) at the same site as the Takeoka Byoin on 314 “M” Street. By 1913 the Eagle Hospital started, which lasted until 1920 before going bankrupt. The owner of the defunct Eagle Hospital studied approximately two years about how best to start another hospital. As he studied at the various hospitals in Sacramento he noticed the harsh treatment accorded the Japanese, and he was even more determined to establish a hospital.

By 1922, he purchased the site of 1405 4th Street to build his hospital. Originally, the building had two stories, but additional third floor was added and completed in 1924. He named this hospital Agnes Hospital after his daughter. This hospital was the first to offer full services to the Japanese community. It was reported to have modern surgery rooms, x-ray equipment, private rooms, and even an interpreter service. By 1932 or 1933, the hospital had to close because of bills that were outstanding and no real way of collecting from the Japanese patients who were not able to pay their bills. This is an example of the weakness or financial ruin that can result from a community that was too interdependent.”2

Although seventy-eight years have passed from the start of the Takeoka Byoin to the demise of City View Hospital, certain features appear similar in both the early and recent Japanese hospitals. Perhaps more than most ethnic hospitals, the Japanese hospitals served almost exclusively the Japanese community, never gaining the widespread acceptance enjoyed today by the French or Jewish hospitals. Individual doctors played prominent roles in establishing each hospital, whether it be Dr. Tashiro in Los Angeles, Dr. Okonogi in Fresno, Dr. Kawabara in San Jose, or Dr. T. Miyakawa who founded Agnes Hospital mentioned above. The Japanese community has always played an important supporting role, buying up stock for the early proprietary hospitals or holding fundraisers for the later nursing homes and for City View itself.

Excessive interdependence brought down Agnes Hospital, and in a modern version contributed to City View Hospital’s troubles, when a Japanese hospital was once again burdened with Japanese patients from whom it had no way of collecting the full amount owed. However, the reason this time was the DRG system, not the Depression.

The case of City View is exemplary in highlighting the importance of good community-hospital-medical staff relations to the survival of such hospitals. Quite possibly the whole crises could have been averted, had the Board of Directors made a habit of keeping minutes, publishing annual reports, and being more willing to negotiate with the doctors and the community. However, the community became polarized because of perceived unwillingness to communicate, seemingly more on the part of the Board of Directors than on the part of the medical staff or community.

But certainly, the hospital did lack enough patients to cover its operating costs. This study showed me how the DRG’s took effect at this hospital, raising the percent occupancy rate required to break even. Measures could possibly have been taken ahead of time by the medical staff to increase admissions.

Descriptions of the old hospitals frequently mention their modern equipment. And the presence of modern equipment is even more a selling point now to patients and physicians—one increasingly hard to come by for small hospitals.

The Jewish hospitals have gotten around this limitation by becoming large hospitals themselves. Einstein and Cedars-Sinai are two such institutions. They have also attracted a greater mixture of patients as time goes on, yet still maintain their special dietary services.

Perhaps the move by the medical staff to St. Vincent’s is thus a step in the right direction, with Japanese-only Japanese hospitals a thing of the past. But the staff and the community as of yet desire their own facility.

In regards to the earlier hospitals, I was surprised by their number and variety—and with the comparative ease of their construction compared with building one today. Back then, a large home or enlarged clinic could—with some modifications—become a hospital. In fact, a doctor’s home could become his hospital, making hospital care seem more like a cottage industry, unlike today’s aggressive business climate in health care.

Finally, concerning any future Japanese hospitals, I think they can be unique and excellent training areas for ethnically oriented hospice care, pre-medical community health awareness, and ethnically oriented research programs. They would hold lessons for cross-cultural medicine researchers that could be gained nowhere else.

(END)

Author’s Note: The last remaining Japanese American hospital, Kuakini Medical Center, in Honolulu, Hawaii, continues to carry out Nikkei oriented clinical care and research. See their webpage at www.kuakini.org. (July 31, 2010)

Notes:

1. "City View Finances Discussed," Rafu Shimpo, 26 June 1985, p. 1.

2. Maeda, op. cit., pp. 55-57.

© 1986 Troy Tashiro Kaji