When Bob Naka was a UCLA student in the early 1940s, there was a campus bridge that led from the parking area toward the Physics Building. “There was a deep ravine under that bridge,” he recalled. “It’s since been covered over, but you can still drive over it. People probably wonder, how come this road has sides to it?”

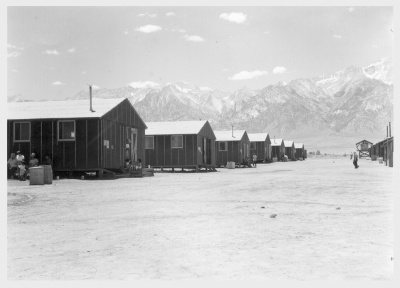

That is the UCLA that Naka, 86, remembers. The Concord, Mass., resident hasn’t been back to campus since the 1950s, just after the events of World War II wrenched him from a comfortable student’s life to that of an inmate at the Manzanar Relocation Center. Now, nearly 60 years later, Naka is returning to UCLA to receive an honorary degree in place of the one he was never allowed to complete.

He'll be joined by his fellow Japanese-American classmates who were forced to leave UCLA in 1942 and sent to internment camps throughout the United States. UCLA is hoping for an attendance of at least 50 former students (or family representatives, in the case of recipients who are infirm or deceased) at an honorary degree ceremony to take place on Saturday, May 15, in Schoenberg Hall.

“In some respects, UCLA’s interest in recognizing the injustice of FDR’s Executive Order 9066 and the impact it had in disrupting the UCLA education of more than 200 Japanese American students goes back to 1992, when the Asian American Studies Center (AASC) worked to get [former student] Aki Yamazaki her UCLA diploma,” said Professor Emeritus Don T. Nakanishi, chair of the campuswide task force appointed by Executive Vice Chancellor and Provost Scott Waugh to organize the degree ceremony.

The awarding of Yamazaki’s diploma in 1992 was part of the AASC’s yearlong series of events commemorating the 50th anniversary of the mass removal and incarceration of 120,000 Japanese Americans, Nakanishi added.

This year, all the remaining eligible former students will get a chance to receive their long-overdue degrees at the May ceremony. The UCLA task force has been working extremely hard to get the word out, enlisting the help of the California Nisei College Diploma Project and the UCLA Nikkei Student Union to publicize the event. The committee has also been sending flyers to churches and other Japanese-affiliated organizations and media.

For Naka and the other Japanese American students who ended up finishing their degrees at other schools, UCLA’s honorary degree will be the perfect capper to their academic careers. Naka was forced to withdraw from UCLA in May 1942 — after having completed three-quarters of his sophomore year — and was sent to Manzanar with his parents.

With the help of Manzanar teacher Helen Ely, however, Naka and several other students were able to enroll at other colleges that were located away from the West Coast. He completed his electrical engineering degree at the University of Missouri in 1945 and went on to receive a master’s degree from the University of Minnesota in 1947 and a Ph.D. from Harvard University in 1951.

While at the University of Minnesota, Naka met fellow student Patricia Ann Neilon, whom he married in 1949 and with whom he has four children: David, Holly, Michael and Peter. All the while, he continued to work his way up the engineering ladder.

Naka’s impressive career began almost immediately with his very first job at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Project Lincoln, where he worked with other engineers to invent an automatic radar signal detection device that was used across North America to detect the presence of invading Russian bomber planes. On the flip side, Naka was soon enlisted to design aircraft that could escape detection, and his work on the U-2 and Oxcart aircraft became the precursor to stealth technology.

From 1969 to 1972, Naka served as deputy director of the National Reconnaissance Office (NRO) in Washington, D.C., a spy satellite organization whose existence the U.S. government would not acknowledge. Years later, when Naka sat down with his former boss, John L. McLucas, the two men reminisced about how the time they had spent at the NRO was the most rewarding of their lives.

“John remarked that ‘only in America’ could I have traveled from being a distrusted American to one of the most trusted Americans,” Naka said. “We both marveled at that, and I thanked him profusely for his faith in me.”

After his service with the NRO, Naka spent three years as chief scientist of the U.S. Air Force, followed by 10 years as vice president of engineering and planning for GTE Government Systems Corporation, a communications company. He retired in 1988.

For his part, Naka remembers his UCLA days with fondness. “I thought life at UCLA was very, very pleasant. And I made very good grades,” he said. “In fact, the curious thing was that I outperformed all my high school classmates. Something happened that made me more connected to the classwork at UCLA at that level.

“My math teacher in high school, Ms. Thornton, came out to UCLA several times to talk to those of us who had gone to UCLA. And she said to me, ‘Something’s happened here. You’re outstripping everyone else,’ ” Naka said, laughing. “I told her, well, I think it’s kind of fun being here.”

Naka is scheduled to speak at the May 15 event at UCLA and will be joined on the program by Chancellor Gene Block; Professor Lane Hirabayashi, chairholder of the UCLA George and Sakaye Aratani Professorship in Japanese American Redress, Internment and Community; California Assemblymember Warren Furutani; and Edward Kobayashi, president of UCLA’s Nikkei Student Union.

“It’s never too late to join with others throughout the nation in recognizing that the mass removal and incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II was wrong,” Nakanishi said. “More than 700 UC students had to terminate their studies at UCLA and other campuses, and most never received degrees from these institutions.

“By honoring these former students, we acknowledge the many diverse contributions they made to campus life in student government, athletics and academics, and formally welcome them back to our academic communities.”

It’s too late for some students, although they will undoubtedly be there in spirit. Ron Takasugi knows that his father, Naoyuki, who died in November, surely would have attended the ceremony. Nao, who was forced to leave UCLA for the Gila River Relocation Center 50 miles southeast of Phoenix, was a former state Assemblyman and mayor of Oxnard, Calif.

“Dad was a true-blue Bruin all the way. Even though he graduated with a Temple and Wharton degree, he always supported UCLA and encouraged us to go there as well,” said Takasugi, who graduated from UCLA along with two of his four siblings.

“I remember him telling me that even with the war breaking out, no one ever treated him badly or shunned him and his other Japanese American friends. Life on campus is somewhat sheltered from the real world, and the faculty and other students did not have the same prejudices or views that the government had at that time,” he said.

“Dad would have been so proud to have received his diploma from the college he loved so much.”

* * *

UCLA Honorary Degree Ceremony

Saturday, May 15, 2010

UCLA Campus

Former students and their families are asked to contact the University to confirm eligibility.

Please call 310-794-8604 or email tricial@support.ucla.edu

* * *

* This article was originally published in UCLA Today .

© 2010 UC Regents