On September 18, 1942, finally, after the Atchison Topeka & Santa Fe train engine, the last of the different locomotive engines that took their turn pulling our passenger train carrying us Japanese evacuees aboard through their own railroad company jurisdictions, we arrived at the small farming town of Granada, Colorado. It took three days of confined discomfort. The seemingly endless travel time was caused by the priority given scheduled passenger, military and freight trains over our “special” evacuation trains, which had to pull over to side rails numerous times to let them pass. According to George and Shig Hirano, who were on one of the trains from Merced, “we well remember the jolts when the changes were made. Were the engineers having a good time punishing the ‘Japs’?”

We cautiously stepped down out of the old passenger cars and waited, standing or sitting on suitcases in the Colorado dirt, for the U.S. Army trucks to take us a mile and a half to the barbed-wire encircled camp compound dotted with armed guard towers.

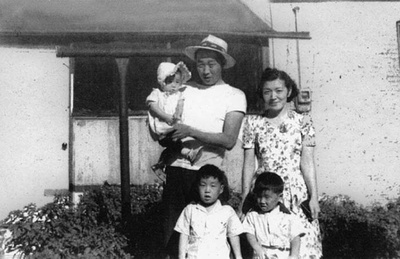

I can only imagine how my mother, 25, must have had to clamber onto the high truck bed carrying our infant sister, Sandra Yoko born just last month in the Merced Assembly Center. At least because of that, they did assign the two of them to a sleeper car along with pregnant women and the infirm for the strenuous trip. Our father must have had his hands-full caring for my brother Stanley and me, now 3 and 2-year-old, respectively, in the regular car with hardwood straight-up passenger seats in which we had to sleep sitting-upright.

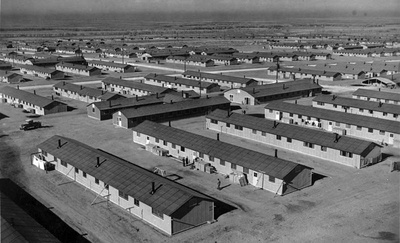

The “relocation camp” was renamed Amache instead of Granada, the initially given name, because of the postal delivery confusion that would be created by two “towns” with the same name. Ironically, the -Amache population was to be more than ten-times greater than that of the town of Granada, in Prowers County. Even though Amache had the lowest population of the ten concentration camps, it was the tenth largest populated “city” in the state of Colorado.

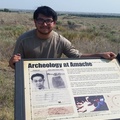

I only recently heard the pronunciation of Amache as Ama-che (like in say) when I was a volunteer worker with University of Denver faculty and students on an archaeological dig in Amache in July 2008. All my post-war-life I’ve heard Japanese Americans pronounce it as Ama-chi, giving the name a Japanese sound as opposed to the correct Cheyenne pronunciation. On a whim I looked up AMA in the Kenkyusha’s Japanese-English Dictionary, which offered many meanings, but the two that caught my eyes were “priestess” and “hussy.” I chose priestess. In the dictionary, Chi meant “place.” I thought since Amache, a Cheyenne Indian chief’s daughter, after whom the camp was name was more closely a “priestess” as opposed to a “hussy.” Playfully translated, the name/ place fits; doesn’t it? Amache was married to John Prowers after whom the county, in which the camp was located, was named.

We numbered 481 evacuees in the very last train load from the Merced Assembly Center in Central Valley, California. There had already been eight other groups that were railroaded from Merced. In September, the trains delivered: 557 on the second, 557 & 550 on the fifth, 553 on the eighth, 527 on the ninth, and then 529 & 527 on the 16th, for a total of 4,493 evacuees from the Merced Assembly Center.

Before that, on August 27, on the first trainload from the Merced Assembly Center, there was an advance work party of 212, which included my Uncle Hirofumi “Hippo” Okamura, who volunteered at the adventurous age of 19. In the photo below, Hippo leans on the truck side-rail with arms crossed in a dark shirt and hatless. To his left, in a jacket wearing a white shirt is Peter Masuoka, whose brother Ed “Butch” eventually married our auntie Yuki Okamura in 1943. Peter died in France in 1944, KIA, and was posthumously awarded the Silver Star. The Masuoka family had four brothers in the U.S. Army during WWII. Only sister Margarette was in Amache with their parents and a fifth brother, Takegi, was living in Japan.

Following Merced, six separate trainloads arrived in Granada from the Santa Anita (Race Track) Assembly Center over the remaining September days, from the 19th to the 30th, for a total of 2,942 evacuees from Los Angeles to bring the Amache population up to a total of 7,435, which includes the first baby, a girl born in Amache on September 22, 1942.

Our mother must have had to cover baby Sandra’s tiny head to protect her from the sand swirling in the wind. Winter’s coming chill is evident as our family begins the registration and barrack assignment process. My father evidently volunteered on a construction project shortly following our arrival because Amache (initial construction of which didn’t even begin until June 1942) was far from being completely functional and winter was imminent. This I discovered in 2008 when I became a volunteer in Amache, 66 years later as an archeological dig assistant with Dante Hilton-Ono, my 16-year-old grandson. While there on this project organized by the University of Denver, I found my father’s unmistakable signature along with others on a concrete block pedestal for a hot water boiler. They all evidently had a hand in building the concrete block and had proudly signed their handiwork on the yet wet cement. For more details, about this, see “Significant Signature.”

As mentioned in “A Sunday Drive – Mommy’s Birthday,” sure enough, on my mother’s next birthday, December 7, 1942, the temperature in Amache was 10-degrees Fahrenheit! Living in hastily constructed barracks with thin walls must have found our family with infant sister all huddled around the coal burning heater in our barrack room. Min Tonai, President of the Amache Historical Society, recalls that “later that month, the temperature went down to minus 22 degrees Fahrenheit as an Arctic storm coursed through the plain states.” Wishfully, I try to imagine that the mess hall cooks had baked a birthday cake for my mother.

Early 1943, my father was recruited, along with George Dote, from Los Angeles, to try out for a job in Denver. On February 1943 they were hired by the British Political Warfare Mission (BPWM) to do English-Japanese translation and for radio broadcast of that material to Japan through San Francisco. The BPWM in a joint program of radio propaganda with the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) shared the Denver KFEL radio station facility on two different shifts in the downtown Albany Hotel. The OWI had up to eight Japanese Americans on their broadcasting staff, while the BPWM had four The two others, were Gish Endo of Walnut Creek, and Frank Hattori, Seattle, from the Heart Mountain and Minidoka concentration camps, respectively.

I was able, with grant funding from the California Civil Liberties Public Education Program and my reparation, to produce a video documentary in 2002, “Calling Tokyo: Japanese American Broadcasters of WWII.” This little known story about two groups of Japanese Americans and their “secret” work for the Allies during World War II is available on DVD in the Japanese American National Museum Store; proceeds go entirely to the National Museum.

My mother, sister, brother and I joined our father in Denver in July 1943. In October, my mother required surgery, of which I could find no recorded details, but Amache records indicated that our grandmother, Owai Okamura was released from Amache “to travel to Denver to help her daughter, who was about to have surgery.”

On May 27, 1944, our mother delivered our brother, Victor Katsumi, but as her bad-health-luck would have it, in the very next month our mother was admitted to a Tuberculosis Sanitarium in Boulder, Colorado. We children were accompanied back to Amache by, I believe, my grandmother and/or aunt. My father might have been excused from his war-work to escort us as well. One month-old Victor was placed in the care of our paternal grandparents, Kinsuke and Kotora Ono of Sebastopol. My brother Stanley Kazumi and I lived with my grandmother Owai and Sandra was cared for by our auntie Yuki until my mother recovered and joined us five months later. This separation had to be hard on our mother, but I’m sure she needed the R&R.

As the war was winding-down with Japan’s defeat a foregone conclusion, the OWI-BPWM Denver radio broadcasting program was shut-down in February 1945 and all the broadcasters were sent to join the San Francisco operation to broadcast programs encouraging Japan to surrender. We joined our father after being released from Amache. During the closing of the San Francisco broadcasting program, my father was offered a position in London, but turned it down deciding to help my mother and her parents, Suyeichi and Owai Okamura, restart Benkyodo, their Japanese confectionary business, since their sons were away working or in the military.

In 1948, Uncle Hirofumi “Hippo” returned from Minnesota, where he had graduated from a bakery school after serving in the military occupation in Japan, to take over the operation of Benkyodo and today, his Sansei sons, Ricky and Bobby are managing the family business with their mother, our Auntie Sue.

My mother worked at Benkyodo for most of her life after camp until she had a cerebral hemorrhage in 1990. She recovered fully over a long two-year period thanks to a lot of attentive family support. She worked a little after her recovery, but mostly enjoyed an active, but peaceful, life with her growing family, eventually dying of a heart failure in 1992. Looking back and reflecting on what the Issei and Nisei went through, I can now understand her reluctance to talk very much about those weary war years and our Amache arrival.

* Thanks to Min Tonai, President of the Amache Historical Society and members George and Shig Hirano for their contribution of memory recall.

* * *

On February 20, 2010 there will be a Commemoration Program at the Merced Assembly Center, the Merced County Fairgrounds. For those interested in attending, contact: Bob Taniguchi (209) 631-5645 or taniguchi.r@mccd.edu See also: http://www.mercedassemblycenter.org/

© 2010 Gary Ono