I knew that the Japanese Canadians (JCs) had a rough time during WWII but I did not know how bad it was. I got an inkling of their situation by reading the book, A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America and from Dr. Midge Ayukawa of Canada.

The racism in the West Coast British Columbia (BC) was just as severe as it was in California and this feeling was expressed throughout the whole of Canada with very little positive feeling toward the JCs. The U.S. had a Federal Government that had a conscience of what its Constitution and the Bill of Rights stood for—whereas the Canadians did not. Many influential members of the Canadian government from BC including the Prime Minister were elected on a racist platform. They believed this was the chance for ridding BC of the Japanese race. People of Japanese ancestry had their citizenship taken away and were evicted from the BC West Coast during the early part of 1942.

The potentially dangerous Japanese nationals were arrested and placed in custody (in what was the equivalent of the U.S. Dept. of Justice POW camps) and they were able to claim protection of the Geneva Convention. But the ordinary JCs did not enjoy that protection. The residents of British Columbia resorted to blatant racism which spread throughout the entire country.

The eviction of the JCs was developed independently of the U.S. but in virtual lock-step as the prairie states refused JCs to resettle there. But their sugar beet farmers needed labor and so workers were accepted as family units (as long as it did not cost them any money.) Thus, a number of families who wanted to keep their families intact moved to Alberta and Manitoba. Also federal authorities created road camps but that did not work out well as families were split apart.

The arrangements were quite different from that of the U.S. under the War Relocation Authority (WRA). The U.S. paid for all the expenses of the confinement. The Canadian government confiscated all home and land-holdings of the JCs and JCs were required to pay for their own living expenses. The costs for the Canadian Government was one-third that of the WRA in the United States.

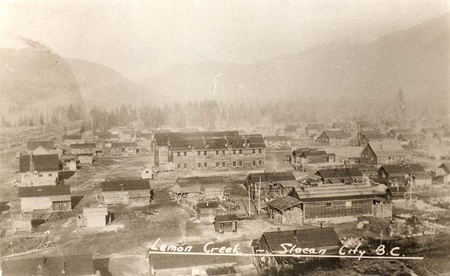

The JCs were crowded into five “ghost towns” scattered through the Kootenay Valley in eastern British Columbia: Kaslo, Greenwood, New Denver, Sandon, and Slocan City. Old hotels built for miners in the late 19th century were “fixed.” In addition, shacks measuring 14 ft by 24 ft were built on nearby pastureland. Outdoor privies, kerosene lamps, outdoor water taps, wood stoves, community-style Japanese baths provided some other necessities. After a record-breaking cold winter, thin tarpaper was provided to cover the shrunken ship-lap lumber outside walls. There was another camp of shacks built from scratch on abandoned ranchland near the town of Hope (Tashme), just outside the 100 mile “protected area”.; Some 12,000 JCs were confined in these “interior camps.” There were no watch-towers nor barbed-wire fences around these camps nor were there soldiers keeping watch as the interior area was in the wilds and was difficult to access. There was only one unimproved road connecting them from the outside world. The roads are better now. No food was provided to the inmates. In the first year, local Doukabours (renegade “peacenik” sect from Russia) sold root vegetables, cabbages, etc. in the camps, and local “white” people opened grocery stores. There were no dining halls. The inmates grew their own vegetables. The government provided medical care using JC doctors and nurses and there was mail service (albeit censored). Primary education was provided with untrained female high school graduates. The government decided that high school education was not their responsibility. After a year, church groups filled this serious gap. (Ayukawa)

Inmates were stripped of their occupations and found that the only work available was hard manual labor at the lowest wages. Typically they earned 22.5 to 40 cents per hour (only a little better than U.S. WRA wages).

The structures put in place by the U.S. WRA to provided practical and financial assistance especially college students, and to advocate for them in their new homes were not copied by the Canadians. Universities were few (about one per province) and they refused to take JC students although much later a few did.

Further, while JAs lost the lion’s share of their property during removal and afterward, there was outright confiscation of JC properties. The British Columbia Security Commission that had promised to protect JC properties but dissipated all assets by auction at fire-sale prices. After deducting the “storage” fees, there was very little left for the JCs. Japanese Americans despite their small numbers, succeeded in altering the nation’s social and political landscape during WWII. The exploits of the Nisei combat units threw into sharp relief the patriotism and American faith of the Nisei. The sacrifice of the Issei and Nisei in accepting removal may thus perhaps be said to have preserved the fundamental liberties of the West Coast JAs. Thus since Canada did not have the outstanding JA military record to back them up their situation was not as optimistic. A few JCs had enlisted before the Pacific War to serve in Europe. It was only late in the Pacific War that a number of JC volunteers were accepted as interpreters in Asia. The Canadian Army did not accept JCs. They had to serve in the British forces but later on they were accepted into the Canadian Army.

In January 1945, JCs that were 16 years and over were forced to sign papers to be removed to Japan. Those who would not were ordered to go east of the Rockies immediately. But many areas refused to accept the JCs. 10,000 signed but many realized their error almost immediately and tried to cancel placing legal procedures into motion. In 1946, 4,000 were sent to Japan and the rest moved east where they settled in the Toronto area and remained there.

In 1952, the Issei were finally allowed to become American citizens. In Canada, their voting rights were enfranchised at the time. The JAs were allowed to return to the West Coast in 1944. This was not true of Canada. It was in 1949 before Canada abandoned its position of ridding the nation of the Japanese. The Japanese Canadians were finally allowed to return to the West Coast of British Columbia at the late date of 1949.

Both the U.S.A. and Canada gave redress payments (U.S. $20,000 and Canada $21,000Cn) to those (still living) that were affected by the World War II eviction.

INFO SOURCES: Book: A Tragedy of Democracy: Japanese Confinement in North America by Greg Robinson, 2009, 397 pages Columbia U Press. Details of camps and photo are from Dr. Michiko Midge Ayukawa of Victoria, BC, who spent four years during WWII in the Slocan Valley camp. She is a historian specializing on Japanese Canadians. Thanks also to the encouragement of Harry Honda.

* This article was originally published in November 2009 issue of South Bay JACL newsletter.

© 2009 Ed Mitoma