Summer 2010 Archeological Dig at Manzanar National Historic Site

MANZANAR NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE, NEAR INDEPENDENCE, CA — Since Congress established Manzanar National Historic Site in 1992, National Park Service (NPS) staff and volunteers have contributed much sweat and many hot summer hours to revealing Manzanar’s unique buried gardens, amazingly well-preserved beneath feet of Owens Valley silt. This year’s quest: Block 15.

Japanese Americans arriving at the “Owens Valley Reception Center,” in the spring of 1942, were confronted with daily dust storms that coated belongings and occupants, obscured visibility, and plagued respiratory systems. Some people donned World War I surplus goggles to protect their eyes when venturing outside their barracks.

Recognizing the seriousness of the situation, with regard to public health and morale, Japanese Americans and War Relocation Authority (WRA) staff promoted the planting of lawns and gardens. An August 12, 1942 Manzanar Free Press (MFP) headline read, “LAWNS…vs. dust,” stating, “So that Manzanar’s dust troubles may become a thing of the past, Manzanites are industriously planting lawns between barracks.”

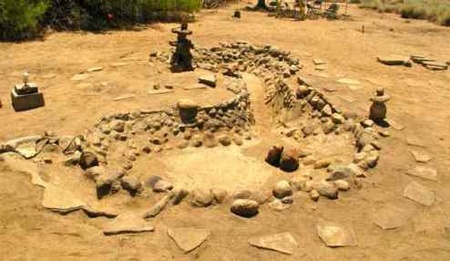

Under a subheading, “FISH PONDS APPEAR,” the article identifies one specific garden: “One of the most beautiful fish ponds in the center is found at Block 15 recreation hall. The pond is kidney shaped with a miniature bridge at the narrowest points. Roy Sugiwara, former gardener, and Keichiro Muto, former flower grower, designed and constructed the pond.”

What started as a dust mitigation project produced surprising and long-lasting results. Ornamental gardens sprung up all over camp, including a large community park, half a dozen mess hall gardens, and dozens of individual gardens. In October, 1942, the MFP described the camp as follows: “Six months ago Manzanar was a barren, uninhabited desert. Today, beautiful green lawns, picturesque gardens with miniature mountains, stone lanterns, bridges over ponds where carp play, and other original, decorative ideas attest to the Japanese people’s traditional love of nature, and ingenuity in reproducing the beauty of nature in miniature.”

Today, remnants of those gardens survive as inspiring reminders of human courage and creativity in the face of demoralizing humiliation and loss of freedom.

A photograph on display at the Eastern California Museum in Independence shows one such “defiant garden,” small and kidney-shaped, with a small bridge and, most intriguing, two small stone lanterns. Perhaps the work of Muto and Sugiwara? A second photograph, oddly, of a funeral, provides confirmation; barely visible behind the crowd of mourners is the “Lantern Garden.” The caption reads, “Christian funeral service for Chiyo Toyama (28-11-3), November 13, 1942.” The church was in Block 15. A November, 1942 MFP story announcing winners of a “best garden contest,” intensified NPS interest in Block 15. First and Second Prizes went to mess hall gardens in Block 34 and 22, and Third Prize to a “private garden at 15-2-2.”

NPS archeologist Jeff Burton and his team of Yogores (“dirty ones”) excavated the first two prize-winning gardens in the 1990s. However, as of June, 2010, Block 15 was unexcavated, with no visible trace of either the “Third Place Garden” or “Lantern Garden.” Did they still exist? Did the lanterns survive? What did Third Place look like? Those questions helped determine the site for this summer’s dig.

After careful documentation of pre-dig conditions, excavation commenced on June 14, 2010. Twenty-five volunteers, four Youth Conservation Corps workers, and six NPS staff participated. Volunteer Hank Umemoto of Gardena, California recalled, “Enjoying the ten days in the desert sun and witnessing Manzanar’s ‘Buried Treasures of Yesteryear’ slowly come back to life, was a profoundly exciting and rewarding event as well as a nostalgic experience, reverting 68 years to my youthful days at the Camp.”

A layer at a time, Umemoto and others screened and removed over one hundred wheelbarrow loads of dust and sand. Unearthed artifacts told stories of the abandonment of Owens Valley’s largest wartime community: rusty nails, bits of rusty bedstead, marbles and broken bottles, along with charred scraps of tar paper and wood. Excitement grew as round granite stones, rows of stones, and outlines of ponds appeared in succession.

“Third Place Garden” proved to be one of the most unique in Manzanar. The pond has scalloped edges and a large island, an unusual design worthy of its recognition. Even more startling, in the garden west of Building 7, was the realization that Sugiwara and Muto’s lanterns, feared lost, had only been toppled into the pond. Dusted off and stood in their original positions, they once more appeared exactly as in the 1942 photographs! Umemoto offered his tribute, “Although the Issei engineers of magnificent gardens have long passed on, they have left us a legacy, a legacy that peace and tranquility can exist amid the doom and gloom of war and turmoil.”

The NPS is truly grateful for the hard work and dedication of its volunteers. Park Ranger and Volunteer Coordinator Carrie Andresen explained, “They are the primary reason that our visitors can observe the historic rock and pond gardens, left by internees at Manzanar. Their commitment initiates a deeper understanding into the lives of those who spent time here.”

The work this summer answered questions about the Block 15 gardens, and added two “new” attractive gardens that will, hopefully, lure visitors away from their cars and into the heart of the camp, to discover what Manzanar means to them.

* The views expressed in this story are those of the author and are not necessarily those of the Manzanar Committee or the National Park Service.

*This was originally published on the Official Blog of the Manzanar Committee on September 15, 2010.

© 2010 Ted White