I was born in Denver the year after World War II ended and grew up as the only Asian in my schools until I hit Junior High. Until I was five, we lived with my Issei grandparents and Nihongo was all that was spoken around the house. Then when I was six, my parents bought their first house, we moved out and I began attending school. From then on, the only time I heard Nihongo was at family gatherings – and other than at home, that was the only time I saw other Asian faces.

My parents, by example, by actions and by their words communicated to me the need to fit in – to assimilate – to not be the nail that stuck up and needed to be pounded down – so I did my best to do just that. There were only a few times when my differences became apparent to me; once, I was called a flat-faced Nip by a schoolmate whose father had been a Marine and survived the battles on Iwo Jima. On another occasion, some older boys terrorized me by circling around me on the playground while pelting me with snowballs on December 7th to teach me “…not to bomb Pearl Harbor again!”

Still and all, my childhood and youth were not unlike that of most suburban Baby Boomers – summer camps, bicycle rides, swimming lessons, lawn-mowing and neighborhood picnics and games – with the exception of occasional visits to the Denver Buddhist Temple where my father was active (my mother was raised a Christian, so I also went to Bible School in the summers too).

During my junior high school years, I began learning about the expectations that come with being an intelligent Japanese American. The first lesson came from my mother when I forgot the money she’d given me for a hair cut. After the barber finished and I couldn’t find the money in my pockets, he told me to just bring it back later. Embarrassed by this faux pas with a new barber, I walked home and told her what had happened. She told me that he trusted me because I was Japanese American and he knew that I’d be back.

The next came from a teacher who told me of meeting the late Eleanor Roosevelt at an educational conference where Mrs. Roosevelt had commented on the brightness of some of the students there. My teacher told me that her response to Mrs. Roosevelt was “Well they may be smart, but none are as smart as my Rodger. He’s just another one of those super-bright Japanese kids and you know how they all are.” Lacking political awareness or sensitivity at that age, I took it as intended without offense.

Looking back, of course, I can recognize now the stereotypes that were growing in the general culture even then.

Strangely enough, it wasn’t until I was in college that I next encountered overt racism.

While driving home after a night class in the spring of 1967, a car with three guys about my age pulled along side and they began yelling at me for bombing Pearl Harbor and letting me know that they were going to Viet Nam to get back at my cousins for it... If I’d truly been smart, I would have simply ignored them and driven on. Being fuller of myself than wisdom and not fully appreciating their condition, I gave them a one-finger salute and turned right to head home as they turned left. Naturally, this outraged them and they turned around, caught up with me, threw a full beer bottle through my back window then sped away, returning my salute. I got their license number, found a policeman and reported the incident. They were caught, jailed and I had to go to court to testify against them. There I learned that they had enlisted in the Marines and were on their way to boot camp from where they were assured of being sent to Viet Nam. The judge seemed to blame me for getting them into trouble; I ignored him and testified to what had happened. He slapped them on the wrist with a fine to pay for my window and sent them off to war.

After graduating from college, I began working for the federal government as a real estate appraiser – a job that led me to another encounter with my cultural heritage in 1978 when I was 32 years old. I received an assignment to do an appraisal of some old barracks in a remote part of southern Colorado to determine their value for sale to local farmers for housing migrant farm workers. The place was Amache. My visit to the site had an emotional impact that unexpectedly moved me to write the paragraphs that follow; after writing them, I shared them only with those who I thought had a perspective that could understand the feeling behind them.

And now, many years later, I share them with you:

It's a place you really have to want to go to get there. It's not on the way to anywhere and not one of those places where you stop because you happen to be in the neighborhood. I was there only because my job as a government real estate appraiser took me there - I wouldn't have gone on my own, though I knew of it from references in a very few books and the stories of elders in the community. My family was fortunate enough not to have been interned there - or anywhere else.

Interned - that's the euphemism the federal government used in Executive Order 9066 in 1942 - Internment Camps. Sounds so much better than concentration camps, which to many, is what they were.

Camp Amache. Jap Camp. Out on the high plains of southern Colorado near the town of Granada. Once the home of several thousand people of Japanese descent, most born in America and full citizens, with all the rights, honors and privileges appurtenant thereto.

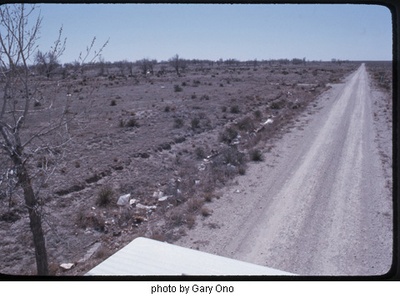

There are no signs on the highway indicating that it is a "Point of Interest," nor are there governmental or historical society markers commemorating its existence. It is memorialized on the U.S. Geological Survey Quad map for that area by symbols for buildings and a notation that the gravel lane leading to it is officially called "Jap Camp Road."

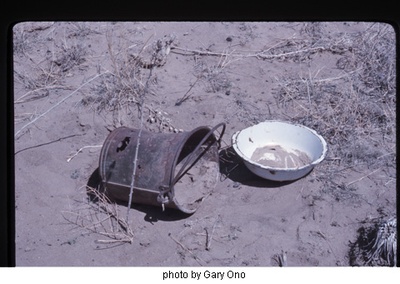

Once you get there, much is the same as it must have been nearly 40 years ago when bewildered, frightened and no doubt disillusioned people were hauled, cattle-like, across the vast emptiness of the mountains and deserts from California: Coyotes still howl in the night, mosquito swarms rise like fog from the bed of Wolf Creek as the day warms and prairie dog holes perforate the sandy soil. Clouds of dust raised by passing cars hang like curtains in the still desert air, the sunsets are magnificent in the way of the desert and twilight lingers long into evening across the flat prairie over the horizon. Barbed wire fences still surround the camp and the current occupants, like the original, are short, dark-haired, olive-skinned and brown-eyed.

But there are differences: The fences are there to keep cattle out, the language is Spanish, there are no guard towers occupied by armed guards and the people are free to leave and follow the harvest, though they too, are prisoners in a way.

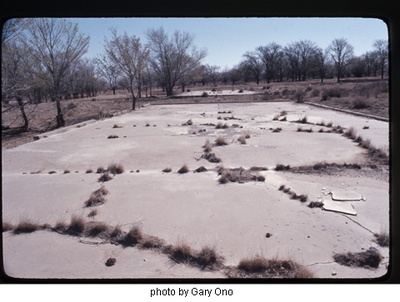

Other than a dozen barracks converted into cramped apartments for the migrant workers, little remains of the original camp. Gravel roads in surprisingly good condition still grid the site. Towering cottonwood trees in orderly rows give living but mute testimony to the horticultural skills of the prisoners, while hardly weathered foundation walls and structural slabs bear witness to the design and building prowess of the Army Corps of Engineers.

The camp cemetery also remains. A lone cottonwood holding a magpie's nest stands watch over the graves and a small, windowless red brick building with a lockless door. Its interior walls are painted white and inscribed in neat rows of fine calligraphy with what must be the names of all who were there. Surprisingly, there is neither graffiti inside nor litter outside.

There, the soil is settling slowly in Masami Murakami's grave. Bright red and yellow poppies bloom around the graveyard (Who planted them? And who waters them in this arid setting?). Sho Fujui was born in 1890, died in 1943 and chose as an epitaph, "To die is to gain." The saddest marker is a small stone that simply says, "Matsuda Baby, December 25, 1944."

Time and man have done much to change the place...and those who were confined there must surely have been changed as well. While much remains unchanged, having been there, I cannot be. (1978)

Until my trip there, the Internment had been an abstraction that hadn’t touched my consciousness. In 1988, when President Reagan signed the Redress Payment Bill, it became more real as family on both parents’ sides received their checks. Although not interned, both families were displaced as a result of Executive Order 9066; both relocated to Colorado – my father’s family from California and my mother’s from Wyoming. For a few months, much of the discussion at family gatherings was about what people were going to do with the Redress payments – and those discussions inevitably led to reminiscences about life before relocation and what was left behind, both physical and emotional in nature. Redress seemed to open the door to disclosure and give my aunties and uncles permission to talk about their experiences and feelings. Three of my uncles had served in the 442nd and they even opened up for the first time in my memory about some of their experiences during the war. It was, for awhile, a magical time that had never happened before nor has it since.

Since that time, my grandparents have all passed away as have my father and many of my aunties and uncles and I mourn their loss and the loss of the untold stories that have been lost with them.

Since that time, I have gone through life with a greater sense of who I am, why I am as I am and have tried to conduct myself in ways that honor the memories of all those who have gone before and the sacrifices they made and the risks they quietly took and the legacies they have left.

And since that time, I have tried, by my words and by my actions to be an example for my twenty-something daughters and to be intentional about assuring that they have a cultural grounding in their heritage. While young, they were enrolled in the Nihongo classes at the Tri State/Denver Buddhist Temple, played with the Junior group of Denver Taiko, volunteered at the annual Sakura Matsuri – and danced each year (with me joining them) in the Obon held in conjunction with Sakura Matsuri. In the community, they have joined me in activities related to the broader Asian Pacific American community; events associated with the Asian Pacific Development Center, the Colorado Dragon Boat Festival, the Denver/Takayama Sister Cities Committee and the APA Commission of the Community Relations Council for the Denver Center for the Performing Arts. And we always make sure to catch the films that come out occasionally (even when they’re bad) like “The Last Samurai” and “Memoirs of a Geisha” and once in awhile an anime film too.

I’ve tried hard to help them understand that while they are different, they are no better or worse than others; different is just different and that they too need to value and respect and honor that part of their heritage that makes them so.

So far it seems to be working; but only time – and the impacts of life and experience - will be the ultimate determinant.

* The images used in this article were taken at Camp Amache in 1977 by Gary Ono on a road trip with his family to Colorado. Read about Gary's own Camp Amache story: "CSI: Amache."

© 2008 Rodger Hara; Images © 2008 Gary Ono