>> Part 2

ISLA DE LA JUVENTUD

On our third day in Cuba, we boarded a chartered plane to Isla de la Juventud, where the commemoration activities were to be held. The flight was less than 45 minutes long.

Isla de la Juventud, or Island of Youth, is located 62 miles south of mainland Cuba and is approximately 1,170 square miles. The name of the island has changed several times, from Treasure Island to Island of Parrots to Isla de Pinos (Island of Pines). Cubans say that Nikkei named it Isla de Pinos after its Japanese translation, matsu (pine) shima (island). In 1978, the name was again changed — this time to Isla de la Juventud to reflect the young people who studied there and the foreigners who worked on the island.

Author Robert Louis Stevenson is believed to have based his novel “Treasure Island” on Isla de la Juventud, where Masaru Miyagi landed in 1908 when he first came to Cuba.

Before we left Havana, we were warned that Isla is very different from Havana. Havana is “Cuba’s big city,” while Nueva Gerona, Isla’s capital, is the opposite. If we needed to purchase things or exchange money, we would have to do it in Havana. Our main mode of transportation, both on the mainland and Isla, was a tour bus. It had to be ferried to Isla for us. There are no taxis on the island; there are cars, but many people walk, or hitch-hike, which is a totally acceptable means of transportation.

We were greeted at the airport by about 20 members of the Nikkei community. They waved the Cuban flag and carried signs welcoming us to their island. It was nice to be so enthusiastically received by people we had only heard about a few months ago.

As we rode from the airport to our hotel, what we saw was mostly open land and propaganda billboards. According to our guide Jesus, Isla de la Juventud is known for its citrus plantations, which are spread out across the island.

Life on the island is vastly different from Havana. There are very few multi-story buildings on Isla. In Havana, pedestrians and cars (pre-Revolution American-made classics from the 1950s) are constantly on the go.

Our hotel, the Rancho de Tesoro, struck me as a symbol of Cuba’s past and present. Built in 1956, it was a single-story complex of about 100 rooms, only half of which appeared to be in use. The back area, which was overrun with weeds, looked like it hadn’t been inhabited in years. A large fountain, complete with an angel at the top, was situated in the lobby. It looked like it might have once been the centerpiece of the hotel. Like other architectural remnants of Cuba’s past, you could get a feel for its opulence just by looking at it. But without water flowing from the fountain, it was simply a reminder that there are no excesses here, not even water.

Most of us shared rooms so we had twin beds. The rooms were equipped with the bare essentials: a wall unit air conditioner, a small refrigerator, a television set and an indoor bathroom. As we had been warned, there were no complimentary bottles of shampoo, tourist-size soap or lotion.

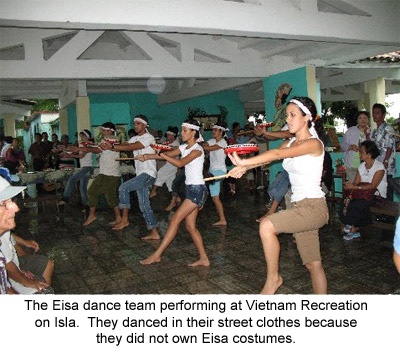

The opening ceremony was held that night at a movie theater in Nuevo Gerona. Besides the welcome messages and commendations from Okinawa, delivered in Spanish and Japanese, there were presentations by local performers. Kiyomi, a leader of the Cuba dance team, mesmerized the crowd with an Afro-Cuban dance. A children’s group sang. The delegations presented gifts to the leaders of the Cuba Okinawa Kenjinkai and its Nikkei umbrella organization, Asociation de la Colonia Japonesa de Cuba. Our “Choode Without Borders” group presented the Eisä costumes and other gifts to them. The night ended fairly early; we were back our hotel before 11 p.m.

The next day was a rather busy one. After breakfast at the hotel, we headed off to the cemetery where Isla’s Nikkei are buried. During a short ceremony held in their honor, Asociation president Noboru Miyazawa pointed out that some Issei died soon after arriving on the island. Each year, the community holds an Obon festival. Miyazawa said maintaining traditions such as visiting the gravesites will ensure that future generations will always know where their ancestors came from.

Our next stop was the Museo Municipal, where a collection of artifacts from the island’s Nikkei families are displayed. Old photographs, suitcases and documents offer a glimpse into the early days of the Cuban Issei. Benita Iha’s book “Shamisen” was on display. There was also a list of Issei and the year they entered Cuba.

Then it was on to the Monumento Nacional Presidio Modelo, or Model Prison National Monument, which is significant in Cuban Nikkei history. The prison was modeled after the Stateville prison in Joliet, Ill., and serves as a reminder that the U.S. and Cuba were once allies.

On Dec. 9, 1941 — two days after Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor — then-Cuban President Fulgencio Batista signed a declaration of war with Japan and its allies, Germany and Italy. A few days later, all persons of Japanese descent were declared “enemy aliens.” While the actions are similar to what happened in the U.S., only men were incarcerated in Cuba: 350 of them Japanese, 50 German and 25 Italians. They were imprisoned alongside convicted criminals. Their wives and children were left to fend for themselves. Some families recalled having to beg for food. We learned that some of the Japanese men spent the time learning Spanish and writing haiku. Because they were considered model prisoners, the Japanese men were moved away from the criminals and placed in a separate unit.

The other interesting piece of history tied to the prison was that Fidel Castro served two years of his prison sentence there for his 1953 attempt to overthrow the Batista regime. He was caught in the mountains and sentenced to 15 years. In 1955, President Batista granted Castro amnesty.

Today the huge buildings that once housed the internees are mere shells. There is no air conditioning so the heat and humidity hang heavy in their air. Standing in the building, I tried to imagine how the Nikkei men survived. They were not allowed to speak Japanese in front of the guards. Their hardship was heartbreaking. It was sad to hear about the wives and children going to the prison to visit their loved one and yet not be allowed to speak to each other in their mother tongue.

It started to rain heavily after we left the prison. We arrived at our lunch spot, an open-air restaurant. Although the rain had made the ground slick, it did not prevent the entertainment from going on. We were treated to an Okinawan Eisä performance by the 10-member Cuba dance team. Although the members did not have Eisä costumes, their enthusiasm and respect for the tradition was evident in their performance. Of course, a gathering of Uchinanchu is never complete without a rendition of “Asadoya Yunta.” Narryman, a yonsei Cubanchu, accompanied Akira Iha, a sanshin instructor from the Okinawa delegation, on her sanshin. As Iha-san continued to play, Kiyomi, from the Okinawa dance team, got everyone on their feet for a lively kachashi. As I captured the moment with my video camera — Cubans, Americans, Brazilians, Okinawans — all swaying their hands and basking in the moment, I felt the depth of the saying, “Yui nu kukuru! ” We truly were of one spirit, of one heart.

Japan’s ambassador to Cuba, Akira Takamatsu, hosted a reception for the visiting delegations. He knew about the difficulties Americans face in traveling to Cuba and kindly asked us about our travel situation. Then he mentioned President Bush’s speech on Cuba, which, coincidentally, had been broadcast a day earlier. Unfortunately, we were out and hadn’t seen it. But when I managed to gather pieces of the speech, which basically listed reasons for maintaining America’s embargo against Cuba, I was at a loss for words. I was experiencing a different Cuba. Had I not taken the trip, I might have believed the agony and sadness President Bush painted in his speech. The Cuba I was experiencing, on the contrary, was a country of proud, kind and highly educated people — people with whom we could share common interests if only we were allowed to openly.

* This article was originally written as a special to The Hawai‘i Herald.

© 2008 Lesley Chinen