>> Part 1

“I never really thought of myself as being an American.”

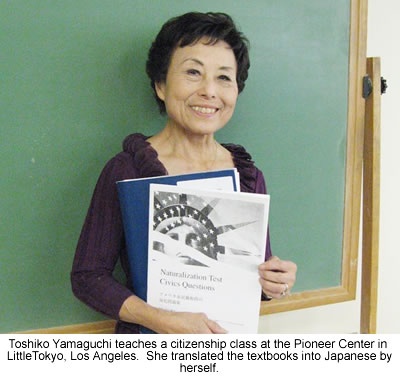

These are the words of Yoshiko Yamaguchi, who instructs a “Citizenship Seminar” at the Pioneer Center in Little Tokyo. She opened up the one and only citizenship seminar for Japanese-speakers in LA County, and has led several “Shin-Issei (New First Generation)” to be born. The words of Yamaguchi-san, who has become an American citizen herself, are echoed by the sentiment of most of these “Nikkei Shin-Issei.” Even while becoming an American national, the heart is still “Japanese”—it stays unchanged.

According to Yamaguchi-san, the merits for gaining citizenship include:

(1) The eligibility to participate in elections

(2) Applying for a Family Trust becomes easier

(3) Inheritance eligible for tax exemption

(4) Ability to apply for SSI (Supplemental Security Income)

(5) Ability to work for federal offices, as well as a promotion if employed by the state or city.

(6) Ability to bring over spouses, parents, and children to America

In addition, in some cases, citizens may be prioritized for certain services such as organ transplants, judiciary services, and educational grants/scholarships.

After listening to the stories of several Japanese who have applied for American citizenship, the most popular reasons for applying had to do with reasons two and three. Even though they may have come all the way over from Japan to America and put a lot of hard work into building businesses and acquiring assets, because they are not American citizens, they will be faced with disadvantageous laws and taxes that restricts what they can leave behind for their children.

“I had a friend who had a horrible experience with that,” said Ms. B, who has resided in America for 18 years. The inheritance tax rates differ greatly between citizens and immigrants. Knowing what happened to her friend—her friend could not pay the large sum of inheritance tax, and brought to tears because she had to sell her beloved home for it—Ms. B decided that she will apply for citizenship for the sake of her children. Ms. C, who has been living in the states for 35 years, is also concerned about real estate. “What will happen to my property if I die?” she asks. Though uneasy about the required oral exam, she also applied for citizenship.

“I want to bring my mother over from Japan,” says Mrs. D, who has spent 25 years in the states. She is concerned about her aging mother, left behind in Japan. There was an option to go back to Japan, but the idea was unrealistic when thinking about her husband and children, so she began thinking about bringing her mother over to America and having her live together with the family. In order for her mother to be able to immigrate, Mrs. D would need American citizenship. Like Mrs. D, another major motivation for attaining citizenship is the desire to bring elderly fathers or mothers from Japan over to the US.

Some people wanted citizenship to take away the hassle involved with re-entering the United States after a visit abroad. With a Green Card, one must stay within American soil for at least half of the year. Even though you may have a Green Card on you, when the number of times you leave and re-enter the country rises, immigration becomes an extremely annoying hassle. That is how America has become these days.

Another thing that caught my attention was the voices of concern over Social Security. This Social Security system can be considered equivalent to the “nenkin” pension plan used in Japan. Although untrue right now, there are concerns over rumors that in the future, the amount of Social Security benefits disbursed to immigrants would be reduced. If this were to happen, immigrants, who have been forced to contribute the same amount of their paychecks to the social security system as everyone else, would not be getting paid their fair share of social security because the system is running out of funds, while the American citizens get their full share. Although I seriously doubt that such logic would ever be accepted, given the concerns regarding Japan-US pension issues in the past, as well as the current economic crisis, it’s no wonder that they feel the desire to obtain equal rights as those given to American citizens.

In the last segment, we covered how the process of gaining American citizenship is relatively easy, and that the passing rate of the interview exam is very high. It seems that the American government is actively increasing the number of its citizens with the purpose of also increasing patriotism. It appears to be true that, through experiencing the process, people applying for citizenship gain a stronger consciousness of being an “American” and a stronger sense of patriotism. The aforementioned Mrs. D explains that “I’ve never thought of myself as an American, but as I began studying (for the exam), my sense of attachment to this country began to grow.” Ms. B also mentioned that “I had no interest in the presidential race before, but now I’m even tuning in to the debates. Politics has become a very close part of my life.” She shows a heightened awareness of herself as an “American citizen.”

However, even among these Nikkei Shin-Issei who have gained their rights as American citizens and have experienced increased self-awareness as an American, many of them have yet to make it a lifelong decision. There are some who have already decided to spend the rest of their lives here, citing that “everyone in my family is American,” or that “I’ve already bought my grave here.” On the other hand, there are those who express concern over the rising cost of healthcare, saying that “healthcare in America is too expensive, so I’d rather spend post-retirement in Japan,” as well as others who “still don’t feel the need for citizenship,” perhaps still feeling a lingering attachment to their Japanese passports. Though the act of gaining American citizenship for a Japanese person seems like the last step towards Americanization, the thoughts and feelings behind the decision can be very different from one person to another.

I, myself, will be qualified to apply for citizenship in a few years, but I haven’t even thought about what I’m going to do. A question from those of us born in Japan—a country that fails to recognize dual-citizenship: why must we lose our Japanese citizenship, though we were born from Japanese parents? Does losing Japanese citizenship mean that we are no longer Japanese? It is a question far, far more difficult to answer than the citizenship exam with a 90% passing rate.

© 2008 Yumiko Hashimoto