Kibei (from the Japanese ki = return, bei = America) refers to an American of Japanese ancestry, who is raised in Japan, but returns to America. She is a perpetual outsider, an American while in Japan, and Japanese when she returns.

My Japanese American story began with my grandmother, who left Japan, one of only two women on a ship bound for America. She landed in Hawaii, where my father, Shinishi Nishimoto, was born, and eventually settled in Fresno, California, where I was born. We were not part of a Japanese American community, which is part of a pattern throughout my life. When I was ten, during the Depression, my father moved to the mainland and began farming in Redondo Beach, California. Times were bad, and he decided to move us to Japan, hoping for better economic opportunities. He had lived in Japan during his teen years, and we retained dual Japanese and American citizenship up until the war.

He sold the farm, relocated us to Hiroshima, Japan and built a house with the money from the farm. Hiroshima was an interesting place and I had an easy life there. I attended the Hiroshima Women’s Institute, a Christian high school. Most of the students were from elite Japanese families, many from families of diplomats and businessmen posted outside Japan. My classmates treated me as an American, not Japanese. Sometimes they teased me. I was called America-jin o-share (“American Show-off’). My parents returned to America after one year, leaving my sister and me behind with relatives. Eventually, I became very unhappy and soon returned to America to join my parents. Now, I was officially kibei.

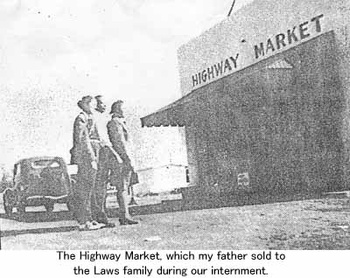

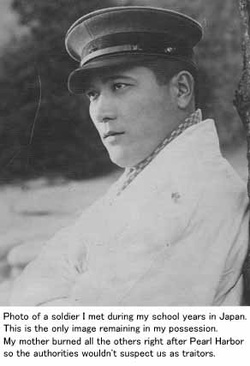

My father, back in America, had given up farming due to allergies, and opened a grocery store in Los Angeles on Imperial Highway and Central Avenue. Again, we lived in a non-Japanese community, where we were treated as Japanese immigrants, although we were born in America. Soon after my return to the USA, Pearl Harbor was attacked. This had a large impact on my family and I remember my mother fearfully burying all the pictures from my life in Japan in the garden, including pictures I had of Japanese sailors I met on the ship home from Japan. I managed to save one.

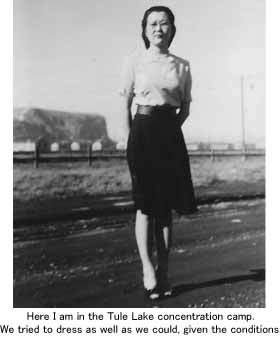

We had been ordered to go to the Santa Anita racetrack, where we stayed in the former horse stables, until the concentration camps were ready. At first we were sent to the camp in Jerome, Arkansas. Although conditions in the camp were very unpleasant, I remember having fun, as a teenager. I had never seen so many Japanese Americans in one place! At first, I was not identified as a kibei. Unlike most kibei, I didn’t have a Japanese accent. Eventually, people found out about our family’s return to Japan. At the time, the government suspected kibei more than other Japanese Americans. They called us “the most dangerous element”. Some of the Japanese Americans in the camp distrusted us as well. My father did not help things by refusing to complete the loyalty forms. Like my father, I also turned in a blank form. As a result, we were sent to a more secure (harsher) camp at Tule Lake. There were many kibei at Tule Lake.

When we were ordered to evacuate, an African American family by the name of Laws offered to watch the store until we returned. Nat Laws and my father made a gentlemen’s agreement and the store was signed over to him. Nat agreed to take care of the store and would turn it back over to my father when we returned. While we were in the camps, Nat sent us money every month. After the war, when it was apparent we wouldn’t be coming back, the Laws bought the store from us for about $3,000 (which was a lot of money in those days). They could have kept it without paying because the title was already in their name, but Nat Laws kept his word. With the money, my parents were able to purchase an entire six flat on Chicago’s south side.

In March 1945, after being freed from the camp, my family moved to Chicago, where my uncle had a business. My first impression of Chicago was of a cold, dismal place without sun. We moved into a small artist community in Kenwood (around 42nd St.), and started life over, with a positive attitude about the future, like many Japanese Americans. As in most of my life, during this period I had very little contact with Japanese Americans. Through a chance encounter with a artist named Else Regenstein, I became involved with the Bauhaus groundbreaking modern art movement. I guess the only prejudice I faced at this time is that I was assumed to be artistic because I was from Japanese ancestry. I studied contemporary weaving with Else Regenstein and Julia McVicker , who had organized the “Reg/Wick” hand weaving studio. I also studied interior design, weaving and art in general at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the late 50’s and early 60’s. Subsequently, I had a weaving shop called “Weaving Craft” where I sold materials, and taught weaving. I helped Else with the second edition of her book “Art of Weaving”, “Weaving Sourcebook” and “Geometrics in Weaving” by providing and producing samples. During this time I also studied Japanese flower arranging and became a certified teacher. I was fortunate to be a part of the legacy of the “New Bauhaus” in Chicago and it was here that I became a participant of a growing artistic community along with my husband, the artist and sculptor, George Suyeoka.

* This article was originally publised in the Voices of Chicago by the Chicago Japanese American Historical Society.

© 2008 Chicago Japanese American Historical Society