São Paulo is a city of hills. When walking around Centro, the downtown area, you may be overwhelmed by the numerous slopes and wonder why a town was built in an area with so many hills.

On January 25, 1554, Father José de Ancheta, along with 13 other Jesuit priests, established a town with Saint Paolo as its guardian angel on the Piratininga plateau (FAUSTO, 1994, p.93). The town was built at the top of the hill in order to protect against a feared Indian attack.

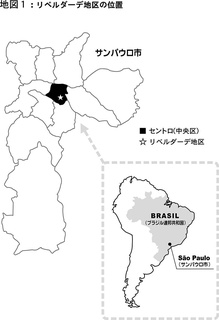

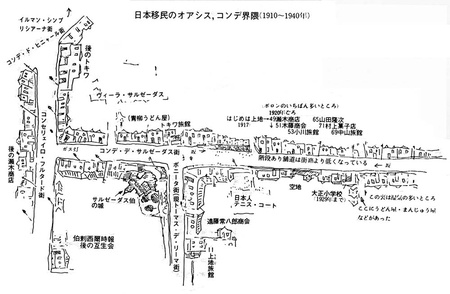

Since then, São Paulo expanded along the surrounding hills, centering around the town built atop the hill. The town site is now called the Pátio do colégio, and is São Paulo’s greatest landmark. From this pátio, one can take a short walk into the Sé Plaza, slip through the side of the cathedral, cross the João Mendes Plaza in front of the courthouse, step out onto Conselheiro Furtado Street and find a steep hill road on the left-hand side; Conde de Sarzedas Street (Refer to Map 1 and 2). Brazil’s first Japantown would be founded midway up this steep hill.1

It is said that the street was named after Count Sarzedas because the count’s mansion once stood on the right-hand side of the entrance into the street, and his manor stretched across the hillside. This mansion, frequently called the “Conde Castle” by the Japanese immigrants who settled in this area, was a symbol of the city. Though the count had long passed away by the 1910s when these immigrants first set foot in the area, they would look up at this castle day and night after climbing up the steep slope under the dizzying, blazing heat (Refer to Map 3).

Even before the first Kasato Maru immigration, there are records of a few Japanese people residing in the city of São Paulo. Further, though the main aim of the Japanese immigration to Brazil was for agricultural purposes, there were ten-odd immigrants who settled within the city. Out of these city-dwelling immigrants, 3 bachelor men and a married couple were free-immigrant labors, while the rest took on jobs such as carpentry, blacksmithing, and textile making. From the passengers who followed the path of the shokumin (colonizers), a few quickly began agricultural cultivation within the city; a man with the help of a free-immigrant boy, a young man hired by an immigration agency, as well as a sister and a brother from Kumamoto prefecture who eventually became domestic workers. There is also evidence that a stowaway and a boat mechanic, who jumped ship, also stayed in São Paulo (Kayama, 1949, p.37). Shūhei Uetsuka, the Japanese Brazil-colonization company agent, also decided to reside in São Paulo (Handa, 1970, pp. 168-169).

Such details of the lives of the initial Japanese residents of São Paulo are difficult to attain now. With any people of a nation, what brought about comfort to immigrant life far from home was native food. Having had a long history with rice, miso, and soy sauce, Japanese people are unable to display their full strength without such ingredients in their daily diet. Because the first, large-scale distillation of soy sauce is said to have begun in the 1920s (Mori, 1995, p.380), the initial Japanese immigrants, though showing vitality through their adaptation to the local cloths and housing, were surely frustrated with life without Japanese rice, miso, and soy sauce.

On the topic of food, the Nikkei Fujisaki Trading Company employees, who settled in São Paulo before the Kasato Maru immigration, are said to have rented a house along São Paulo Street in the Liberdade District near the center of town and had a Japanese couple cook “Japanese rice” for them (Handa, 1970, p.171). The true nature of this “Japanese rice” is uncertain, however, the employees were supplied with miso and soy sauce by the company and so it is possible that they did have “Japanese rice.” Though the agricultural immigrants were able to find arable land, many gave up farming for other professions due to various reasons. The farm deserters, who had nowhere to go, eventually found their way to São Paulo and rejoiced when they came across the Japanese food they missed so much.

Even after the Fujisaki Trading Company moved out of the area, the Japanese couple stayed, and the house became a boarding house for farm deserters. At the time, there were many Japanese immigrants who ran away from tilled farms due to frustration with contracts, conflicts with employers, and racial discrimination. Such ‘boarding houses’ began appearing along Conde de Sarzedas Street and Estudantes Street, and became sort of a nest of outlaws. In this way, many Japanese farm deserters took up residence around what is now called the Conde District and formed the first Japantown in Brazil.

Daily life in the Conde District at the time is vividly portrayed by Handa (1970).

Conde de Sarzedas town (Conde-town for short) was a hill street, and when looking down the hill from above, there were only two or three houses on the right-hand side. However, there were numerous houses crammed along the left-hand side, creating what looked like a stone wall for Piratininga hill, the center of town. At the bottom of the hill there was a scrub bregeon (wetlands) with a small stream (pp.173-174).

The hard-working Japanese people wake up early in the morning. The carpenters are already carrying their tool boxes through the porrón exit and up the hill. Carrying something up that hill seems exhausting… The missus is wearing tamanco (slippers) and appears from the porrón . She is about to leave for the butcher shop…

Looking up the hill, the castle-like red building of Count Sarzedas shimmers under the morning light (pp.185-187).

Though there were aspects of a Japantown exhibited in the Conde Disctict, many Nikkei lived in porrón (basement) and they were still of course, an ethnic minority at the time.

I walked the streets of the Conde District again during the Carnival holiday this year (2007). São Paulo experiences heavy rain during the month of February. Looking up at the rising, giant columns of clouds from the bottom of the Conde hill, said to have been quickly submerged in water during heavy rain, I was deep in thought about the Japanese immigrants who looked up at the ‘clouds above the hill’ a hundred years ago, half way across the world.

Notes:

1. According to the map published in 1930 (Mappa Topographico do Municipio de São Paulo), the Sete de Setembro plaza, near Conde de Sarzedas street, has an elevation of 762 meters in comparison to the elevation at the bottom of the hill of 725.3 meters.

Reference:

Handa, Tomoo (1970), Imin no seikatsu no rekishi: Burajiru nikkei jin no ayunda michi (The History of Life as an Immigrant -The Path of the Nikkei in Brazil). São Paulo Center for Japanese-Brazilian Studies.

Kayama, Rokurō (1949), Iminn yonjūnen-shi (History of Immigrants for 40 years).

Mori, Kōichi (1995), “Shoku bunka wo tōshite mita nippaku kōryū shi jyoron (Introduction to the History of Japanese and Brazilian Exchange through Food Culture)" Edited by Hajime Mizuno/ Editing Committee for Japanese Brazilian Exchange History “Nihon burajiru kouryū-shi: Nippaku kankei 100nen no kaiko to tenbō (History of Japanese Brazilian Exchange -100 years of Japanese Brazilian Relations: Recollections and Prospects)" Japanese Brazilian Friendship 100 year Anniversary Project Organizational Committee pp.377-418.

Takeshita, Masujirō (1938), Zaihaku dōhō katsudō jikkyō daishashin cho (Collection of Photos: The Reality of Life in Brazil for Our Fellow Countrymen). Taishō Photo Studio.

Negawa, Sachio (2020), Imin ga tsukutta machi San Paulo toyogai chikyu no hantaigawa no nihon kindai. University of Tokyo Press.

Map:

Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo(1930)“Mappa Topographico do Municipio de São Paulo No.51.” São Paulo, Prefeitura Municipal de São Paulo.

© 2007 Sachio Negawa